For more than thirty years, I have been spending my winter holidays in Seefeld, a beautiful mountain resort town north of Innsbruck. Over time, I began to ask questions about its history, and especially about what happened during the Nazi period. Recently, a new monument appeared in its cemetery, commemorating the Jewish people who died in the village during one of the last death marches from Dachau. In general, however, this problematic period in Austrian history is not discussed in Seefeld. During our stays, we have also regularly visited Innsbruck; however, while reading Meriel Schindler’s The Lost Café Schindler: One Family, Two Wars and the Search for Truth, I realised that I had never really questioned the city’s National Socialist past. I must have been in too much of a holiday mood to look at everything around me more critically.

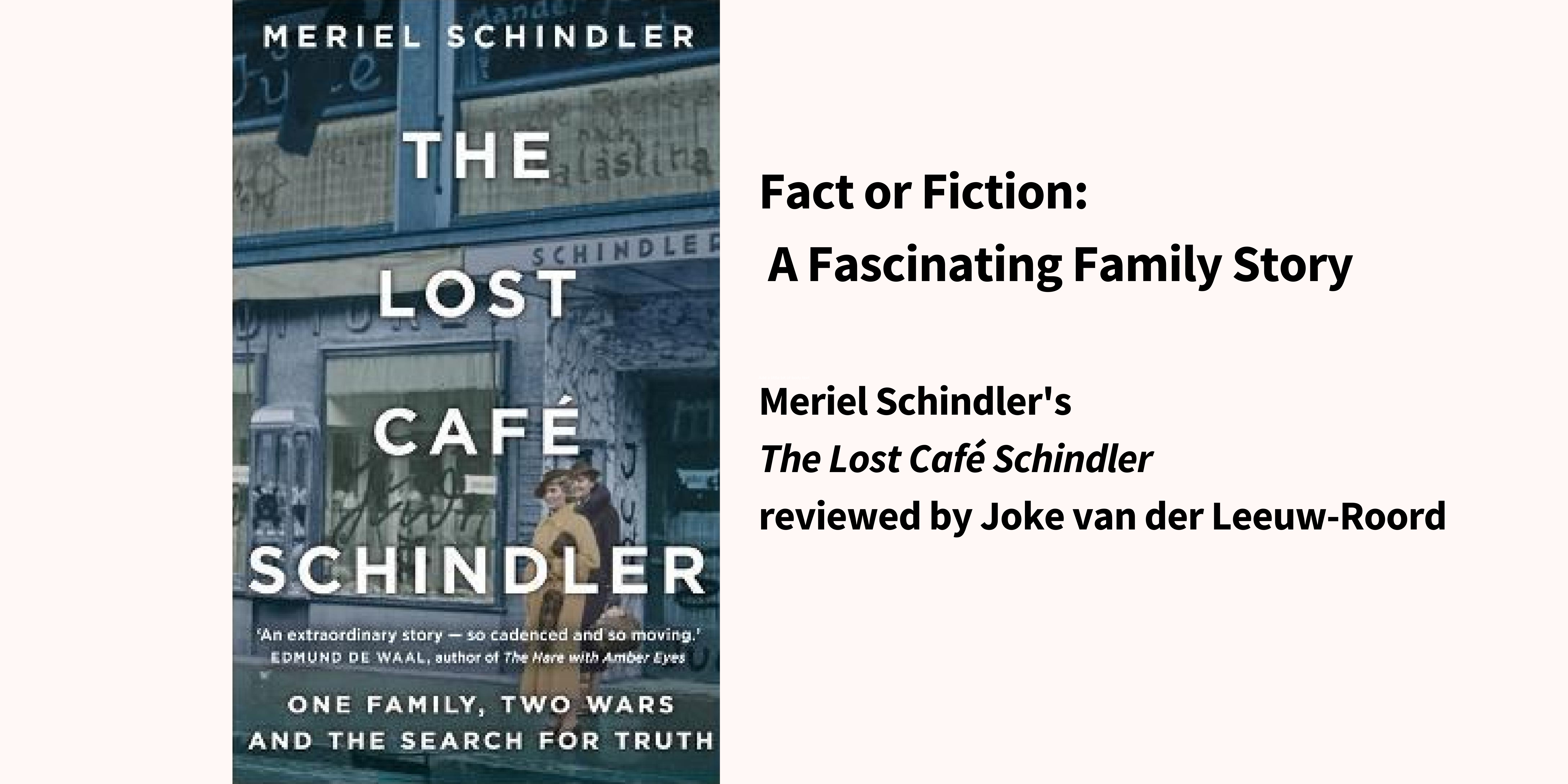

The Lost Café Schindler is a fascinating and eye-opening look at Innsbruck’s history. Set in a beautiful, but rather provincial town, it tells the story of a Jewish family who fell victim not only to the ideology of the Nazis, but also to personal greed. However, the book deals with a much wider narrative, because Schindler has meticulously researched her Austrian Jewish family story and placed this in a larger cross-border context. Her starting point was the death of her father in 2017, with whom she had had a difficult relationship. Throughout his life, he had told her stories and boasted about their family’s relationships with individuals like Franz Kafka and Oskar Schindler. Meriel herself never knew what to believe. She had spent the first fifteen years of her life in London, and was then suddenly moved to a school in Austria with no knowledge of German. Her father played the part of a grand seigneur, always in debt, moving around to avoid the law, and had even been to prison. Consequently, Meriel’s childhood was rather unstable. After her father’s death, the only things Meriel inherited were boxes containing documents, letters and a variety of photo albums filled with images of people unknown to her. She became curious and felt compelled to finally find out what had been fact and fiction in her father’s stories.

The book is a fascinating page-turner, taking the reader from early Austrian industrialisation into the late nineteenth century via the character of Schindler’s Jewish uncle Dr. Bloch, who was Hitler’s family doctor. After discussing the disasters of National Socialism, Schindler relates her research and experiences in the present day. We follow the story of her grandfather Hugo, great lover of the Alps and an active officer in the famous Alpenkorps mountain infantry division, which fought dreadful battles against Italy in the Dolomites during World War I. After the war, Hugo established Café Schindler in 1922 in Innsbruck, where people could not only have coffee and pastries, but also dine, drink and dance from morning one day to early morning the next day. He lost his properties as a consequence of Aryanisation policies, was imprisoned, physically assaulted during the Kristallnacht pogroms, and left Austria for England completely ruined. Finally, with little help from the Austrian authorities, he was able to retrieve the café in the late forties, and returned to Innsbruck. Hugo’s story is the heart of a complex family memoir within the context of the history of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Republic of Austria, Tyrol and Innsbruck.

At the end of the book, Schindler admits that she still is not able to understand her father’s behaviour; however, her search has given us a very good story. She contemplates the ways in which Innsbruck is currently dealing with its difficult past: for example, the site of the concentration camp Reichenau in Innsbruck, where her great-uncle was murdered, has only an insignificant, derelict monument. The Jewish cemetery still exists, and Schindler herself ensured that the names of family members who had perished in the Holocaust were chiselled into the family gravestone. And she discovered that the café is operating again today, in the exact location where it had been before. Upon learning this, Schindler was initially upset, but she describes how she came to the understanding that Das Schindler, as the café is now called, is a great tribute to her grandfather’s work. When I am in Seefeld next January, my goal will be to visit the Reichenau monument and the Jewish cemetery in Innsbruck, and afterwards have a real Austrian lunch in Das Schindler.

English version: Schindler, Meriel. The Lost Café Schindler: One Family, Two Wars and the Search for Truth. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2021. eBook €6,99; Hardcover €32,99. 432 pages.

German version: Schindler, Meriel. Café Schindler: Meine jüdische Familie, zwei Kriege und die Suche nach Wahrheit. Berlin: Berlin Verlag, 2022. Hardcover €32,99. 480 pages.