‘To walk a mile in someone else’s shoes…,’ that is the basic premise for the AVATAR-method. The method is aimed at learning historical empathy as an aspect of historical thinking. Historical empathy is connected to both contextualisation and the meta-concept historical perspectives. Students take the personal perspective of an historical actor to look at certain events and developments within the historical and social context of that actor. The idea is that this makes students both look more specifically at certain topics, as well as that it increases their engagement with the topics and that they start seeing history as more than just a list of ‘dusty facts’.

The Practice

Students appear to have some difficulty with the idea of multiple perspectives. When they approach a topic, most of the time they see it from their own point of view, which they consider to be ‘the valid perspective’ or at least to be ‘more valid than other perspectives’. When working with historical perspectives, students engage topics either from their own point of view, sometimes getting into a ‘judgmental mode’ (thinking in terms of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’), or oversimplifying perspectives, thinking in caricatures or archetypes like ‘the money-crazed liberal (or capitalist) factory owner’ on the one side and the ‘equality-obsessed socialist worker’ on the other. The idea that historical actors were people as well, driven by their own values and needs, in their own contemporary contexts, which differed from our modern context, and with more nuanced views than your average comic book character, seems to be lost on most students.

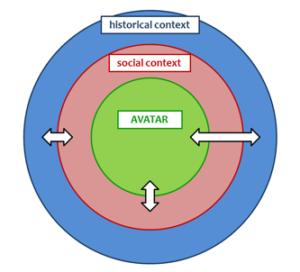

The AVATAR-method aims to have students take specific historical perspectives, while having them take into account both historical context and nuance. The way they approach this is by creating an historical avatar. This can either be an actual historical person or a fictional character, the latter being slightly preferable, because it makes the exercise more flexible. The avatar has a personal profile, which can be as short or as elaborate as you want. This should be built up by going through several tiers or layers, starting from the personal tier (the personal aspects of the individual avatar), followed the tier of the social context (family, friends, colleagues) and the tier of the historical context (time, place and society at the time). The tiers are, to some extent, all connected to each other, as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1: Tiers of the AVATAR method

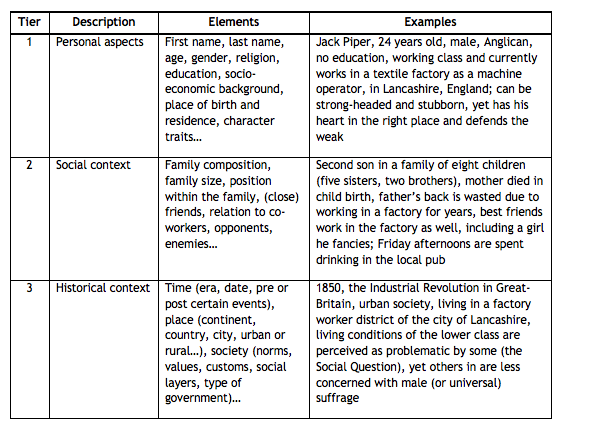

The personal tier should include elements like a name, age, gender, a certain socio-economic background, religion and a place of residence. Students can even go as far as to identify specific character traits (strengths, weaknesses, allergies) for their avatar. This is the tier in which they can use their imagination the most.

The tier of the social context should include information on things like family relations (father, mother, brothers, sisters etcetera), family size (only child, second son in a family with eight children etcetera), co-workers and opponents or enemies. Here they should take into account some historical sources, for example on average family size during that specific time.

The last tier is the historical context, which includes the time, place and society (including the norms, values, social layers, type of government etcetera) in which the avatar ‘lives’ and operates. This requires the most sourcing, because the historical context is ‘set’, with little room for being imaginative. For an example see table 1.

The personal profile of the avatar is the starting point for the activity, in which the avatar ‘lives’ through a certain period of time (for example: a years, five years, twenty years). During that time the avatar gets involved in several actual historical events and developments (examples are the developments in agriculture in the Middle Ages, the protestant reformation or World War I) that took place during the appointed period. Note that the events can be really specific (for example the bombing of Rotterdam and the invasion of the Netherlands in 1940) or more generic (an air raid, some night during World War II). The generic events give you as a teacher some ‘wiggle room’ to have the students work in a specific context.

Table 1: Tiers for creating an avatar

There are a few ‘rules’ (or guidelines) for this activity:

- The avatar cannot die (that would mean the end of the activity);

- The avatar has probable and possible experiences in the set historical context (so no ‘killing Hitler’);

- In some cases: the avatar cannot leave the country (this could undermine the goal of the activity, because this could change the context too much).

The idea then is that students generate a written account of the experiences their avatar has during or in relation to the selected events and developments. For each event the student answers the following two questions for his or her avatar:

- How would my avatar respond to this, taking into account their entire character profile?

- Why would my avatar respond like this, taking into account their entire character profile?

An example can be Jack Piper, the avatar from table 1. In Lancashire the wages in the cotton industry had been reduced during the 1840’s (historical development), which meant that some workers lived in poverty, not making enough money to take care of their families. Jack Piper sees this in his own family and in his neighbourhood. He feels for them and in 1853 he starts a strike (historical event), which lasts for weeks, demanding an increase in wages. During the strike Jack is one of the leaders who goes head to head with the factory owners, who have him arrested. Eventually Jack is released and though nothing much has changed for the workers, he is seen as a hero by his friends and co-workers.

The account can take any form, for example a diary, a (web)log or vlog, a range of letters to friends or family members abroad or something completely different, as long as the account is written from the perspective of the avatar, taking into account his or her character profile and working from historical sources (both primary and secondary).

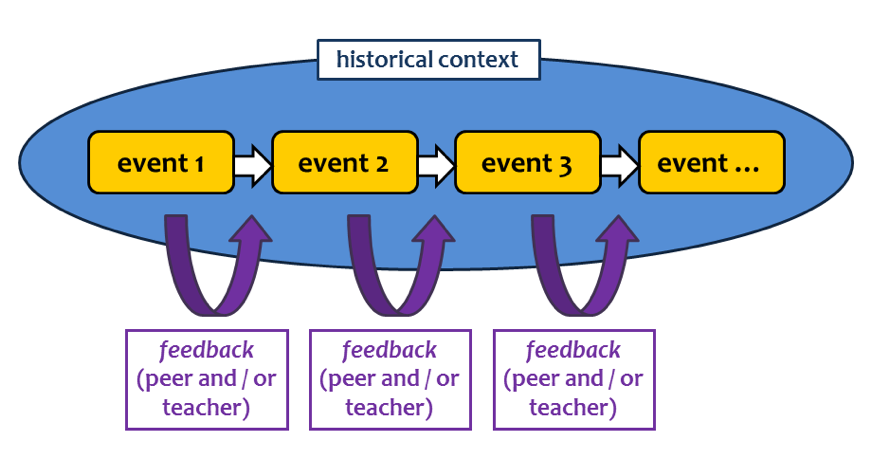

The AVATAR-method can be used for looking at different perspectives in one specific situation, or to research and discuss historical perspectives and how they changed over time. In the latter case it is especially important that either the teacher or peers (fellow students) give feedback on the written accounts of his or her students, so they can grow in the use of the method and get better at describing the viewpoints of their avatars and in general getting more out of the activity. See figure 2 for the progress.

The AVATAR-method has been used in different age groups and with different topics. Of course the level of sourcing and the level of writing depends on the age and experience the students have. An option is to make it a cross-subject project, involving the language teacher and have him or her give feedback on the quality of the writing, while you as a history teacher do the feedback on the level of historicity.

The practice works better for time periods from which (or about which) there are many written sources from several perspectives. Depending on the country the practice is applied, and on the region of the world you would look at, this would mean looking at the time period from 1750/1800 onwards. In addition, it is important to bear in mind that some topics or periods are controversial, and might generate debates and challenges in classrooms. For example: having an avatar who is a high ranking Nazi officer in charge of the deportation of Jewish families in Berlin would provide food for thought for interesting debates, but also be really challenging for students. It is advisable to reserve such ‘challenging’ topics and periods for older and more experiences students.

Obstacles and lessons learned

Using the AVATAR-method, especially in a group that has little or no experience with it, means work (!) for you as a teacher. You will be giving feedback, spotting anachronisms, scrutinizing over details and be confronted with quite divergent outcomes, which means that you as a teacher should have solid knowledge about the time period and historical context in which you let the students set their avatars loose. One of the biggest issues is that students can get stranded on a superficial level, not going beyond stereotypes and not getting into detail on the relationship between their avatar and his or her context. On the other hand it could happen that students go really ‘niche’ with their avatar, getting into obscure details that might require some additional reading and double checking on your part.

The provision of feedback will prove to be the most time consuming part of the practice. Keep in mind that the bigger your group is, the more intense and time-consuming the feedback rounds can be. When students get more experienced with the AVATAR-method, giving feedback will take less and less time and the quality and depth of their work will increase. The first time I used the AVATAR-method, I provided all the feedback myself. The next time I would definitely give students a role in the feedback rounds as well, making it more peer-oriented. This adds to the activity that they have to be critical about each other’s work, as well as that they can show (off) their avatar and all the work they put into it, which might even lead to more motivation. Additionally by reading the accounts of someone else’s avatar, students get insight in other perspectives on the same events.

The effect of the practice

The most important gain from using the AVATAR-method is the high level of enthusiasm and motivation it generates amongst the students. This is likely due to the amount of ownership it provides: students have ‘their own’ historical avatar, through which they approach a topic or time period. This creates a level of involvement with the subject matter that other activities not always provide.

As far as I am aware, no significant formal research has been done on the AVATAR-method and its effects. There are several articles published on the use of avatars in history education (see ‘more information’), but these are more descriptions of experiences in class than a presentation of quantitative results.

The AVATAR-method has been used by students in teacher training as an intervention on teaching historical perspectives during their action research. These aspiring teachers experienced the same thing as I did when I used avatars in class: high levels of motivation and students that got challenged to take into account other perspectives than their own. In that sense the AVATAR-method does force students to look at events and developments from another perspective than purely their own. The method seems to generate both understanding that there are other perspectives in the past (and present) and empathy for the perspectives of historical actors and that you can get to know these perspectives by sourcing, contextualising and reasoning while ‘in someone else’s shoes’.

About the interviewee

Pascal Tak works as Education Manager on board for the Dutch project School at Sea. He has a MEd in both History and Geography, has taught both subjects in a secondary school and has worked as a teacher trainer on a University of Applied Sciences, teaching mostly History Didactics and Action Research in the classroom. For EuroClio he has worked on the Historiana project ‘Innovating History Education for All’.

Background to the project

The AVATAR-method was used with students in a teacher trainer institute in the Netherlands (on a University of Applied Science) in 2015. I was teaching a course on the Dutch Rebellion (1568-1588) and the Dutch Republic (1588-1795) and decided that I wanted to do more with historical thinking and specifically to increase the involvement of the students with the topics. In previous versions of the course a lot of attention went to chronology and economic and political developments in the Netherlands, resulting in long series of names and dates, yet not really delving into the people and perspectives of the time.

Students created an avatar (or several avatars that were related to each other) that lived through the Dutch Rebellion and Republic, reporting on several historical events (like the ‘Disaster Year 1672’) through a series of weblogs.

Additional information

The AVATAR-method as presented here is based on the following literature:

- Sheffer, E. (2009). ‘Creating lives in the classroom’ in: The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Volk, S. (2011). ‘How the air felt on my cheeks: using avatars to access history’ in: History Teacher 46(2) (2013): 193-214.

Written by Pascal Tak (Onderwijscoördinator, School at Sea) in Tilburg on 8 June 2018

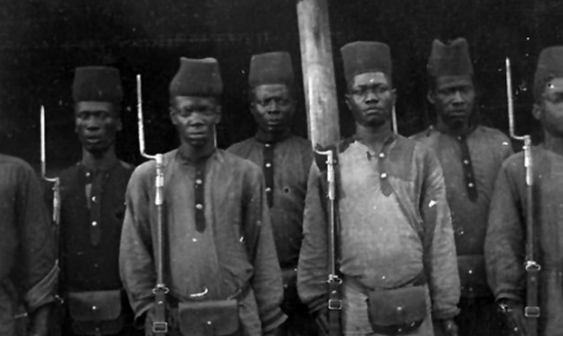

Examples of Discrimination in Football

Football, Colonialism and Migration

Sharing European Histories – Teaching Strategies

Expeditie Vrijheid, a Dutch heritage project in the province of Overijssel

Launch of the Climate Change Educational Kit of In Europe Schools in Dutch!

At the request of the Liaison office of the European [...]