As a response to an increase in new students in the Swedish educational system, the Swedish Board of Education tasked a group of schools and universities to find a way to assess what newly arrived students know in order to provide the best possible education for each student, as well as focusing on their strengths rather than their weaknesses. This resulted in the formation of materials for conducting discourse around history for the purpose of assessing the historical competencies of newly arrived students. This is done in the form of a 70-minute conversation between a teacher and a student.

The assessment is meant to provide valuable insight into what the students are already familiar with, so that teachers can take this into account when creating lesson plans.

The practice

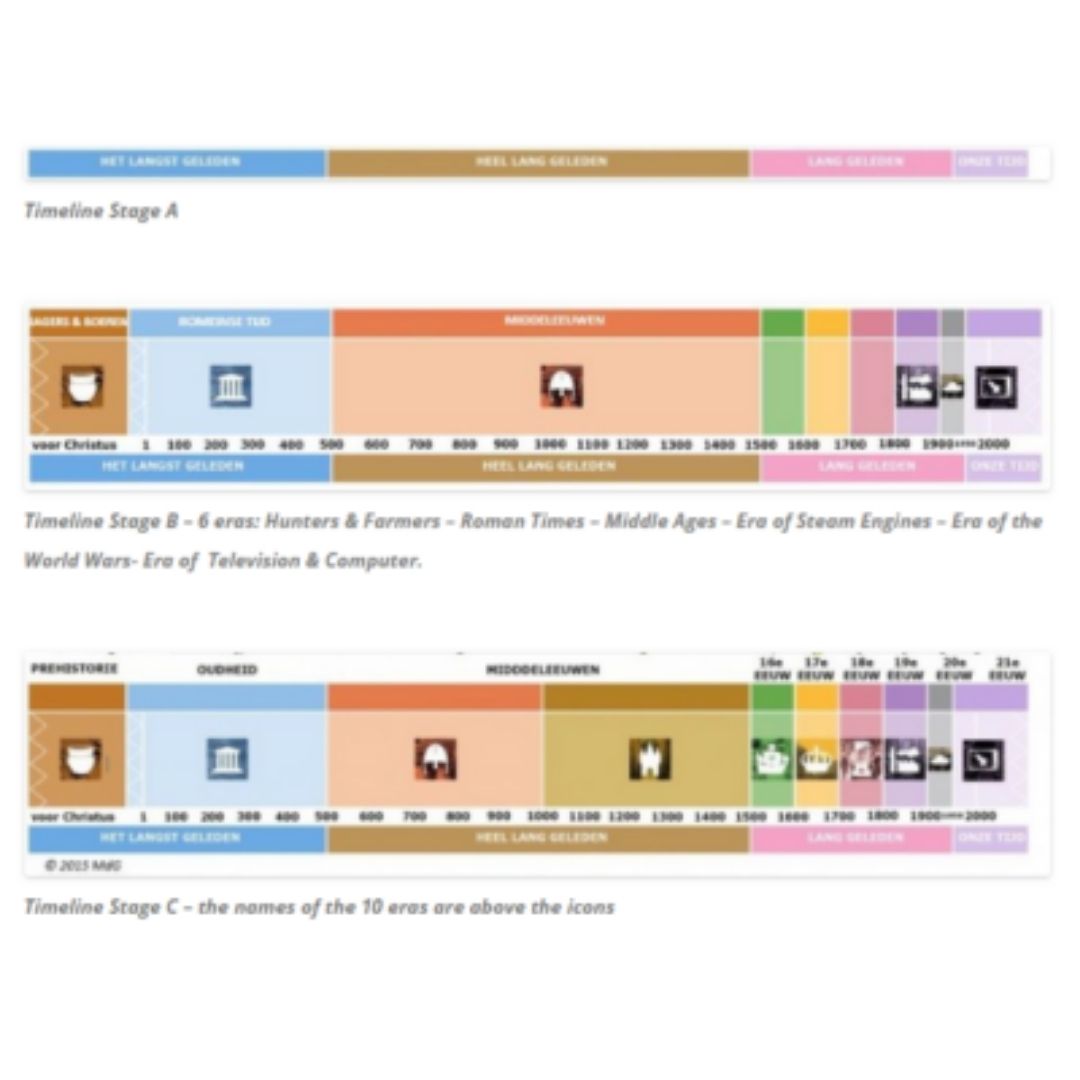

A team of researchers in Sweden developed and piloted an assessment form that is meant to find out the level of historical competencies that the newly arrived students possess. The same assessment is used for a wide age range of students (7-16 year olds) and it takes the form of a 70-minute conversation between the (history) teacher and the student. The assessment is designed to look into capabilities of students rather than their knowledge. For example, focus is placed on construction and organization of history, as opposed to specific content that happened in the past.

The conversation is designed to find out what the students have been taught before as well as what they have picked up outside of school.

The conversation is supposed to be done in the language that the student is most familiar with, along with the teacher that teaches the subject (which in this case would be history). Since the teacher already has some background information from the initial interview, as well as the literacy and numeracy assessments, s/he can choose the content that is likely to be most familiar to the students. The prompts that are used are pictures of various sources and the examples of the use of historical events or processes that the students are most likely to be familiar with, such as migration.

Obstacles and lessons learned

Throughout the duration of the program, several obstacles were encountered. The assessment could be stressful for students, especially those who have had negative experiences in the past, which are not always known to the teachers beforehand. This issue can be solved by creating a relaxing atmosphere and not putting pressure on students to answer the assessment by pausing or stopping the assessment when necessary.

It is also difficult to know beforehand what historical content students are familiar with and which they are not. Therefore, the focus is placed on abilities rather than knowledge, and it offers a choice of topics that the teachers giving the assessment could choose from. When necessary, students are encouraged to draw information from world history and history of everyday life and migration, as these topics are more likely to be familiar to newly arrived students. To help with the language barrier, interpreters were used during the assessment, historical sources that are included are mainly visual, and numeracy and literacy evaluations were translated into the students’ mother tongue.

The quality of the assessment also is dependent on the level of competencies of the person conducting the interview. To ensure that the teachers giving the assessment had the knowledge and the skills to process the information, a series of trainings were organized across Sweden, as well as the development of video tutorials and support packages.

The time investment that the schools have to put in in order to implement the assessment remains a challenge. Due to the optional nature of the subject-specific assessment, it is up to the individual school or educator to decide whether to implement the assessment or not. It should be noted that the assessment is best suited for older students, as younger students are more likely to be at the same level as their Swedish peers.

The effect of the practice

The educators that were involved in the development, piloting and testing of the assessment were really excited about the program. At the same time, students that participated in the piloting exercise indicated that they very much liked the one-on-one approach because they had the feeling that they were taken seriously.

The assessing package for history has been publicly available since the fall of 2017. While the Swedish Board of Education has made some parts of the assessment mandatory for schools, the subject-specific part of the assessment still remains optional.

About the interviewee

Cecilia Axelsson Yngvéus is an Assistant Professor of History Didactics, Malmö University, Sweden. She has a PhD in History Didactics, Meditation and Learning in Museum. She is a writer of support material for assessing history in upper secondary schools for the Swedish National Agency for Education and is a team leader in the Agency’s project on assessing newcomers’ knowledge of history.

Background to the project

The project was initiated by the Swedish Board of Education. The Board wanted to find out what relevant competences newly arrived student haves, and which skills they still need to develop. The mapping of historical competences is part of a bigger assessment, including an interview about previous education, as well as a literacy and numeracy assessment. The work with constructing the material for assessing the four social studies subjects, started in 2013 and finished in 2015. The general assessments are mandatory for all schools and the subject-specific ones are optional. The assessments were made by a national consortium of universities and schools across Sweden, including Malmö University.

Additional information

The Swedish Board of Education has made several support materials available for teachers in order to use the assessment in the classroom: There is a guide for teachers, with a description and guiding principles that clarifies to teachers how to use the form, a YouTube channel with explanatory videos about the assessment that teacher can access, and there is a summary statement that helps the teacher providing the assessment to quantify the results and progress.

Written by Steven Stegers (EuroClio – Inspiring History and Citizenship Educators) based on an interview with Cecilia Axelsson Yngvéus (Malmö University) in The Hague on 6 January 2017.