This Teaching Practice was created by Jan Siefert

Jan Siefert studied History, Biology and German at University Duisburg-Essen. He focused on the History of Medicine (History of the great plague 1348-1352) and Mentality of Samurai in Tokugawa-Japan. He has also taught German at the International University of Kaifeng. For the past ten years, Jan has been teaching Global History at a middle school in Germany and has also been involved in publishing both scientific and school materials. His dissertation is about the empirical measurement of intercultural understanding, focusing on Japanese History. His actual project focuses on the effect of digital materials on History classes.

JAN'S INSPIRATION

"I finished high school in 2004 and since then history classes have not changed much. But the world has changed a lot since then!"

INTRODUCTION TO THE TEACHING PRACTICE:

In Jan's global history classes, he focuses on intercultural understanding or the so-called history of mentality and personalisation, as common principles.

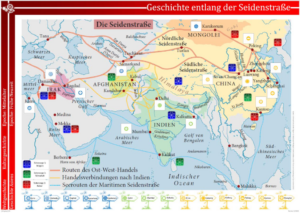

Drawing materials from his Ph.D. about the mentality of the samurai in late Tokugawa-era and his current project map for the silk road, he uses fictional texts and narratives to teach about global history. These types of sources, on which the teaching practice is based upon, seem to be more suitable than more traditional factual and historical sources for the purposes of teaching Global History.

To visualise places and routes where history took place (many students find it hard to imagine or picture these), Jan organises lessons following multiple points of interest on a map. In every city or place, as well as interesting events, there is an effort to connect it to a piece of history and geography.

APPLYING THIS TEACHING PRACTICE:

Teachers may choose a topic such as the Silk Road or the Roman Empire, and instead of exploring it in traditional chronological terms, they can look at social practice or phenomenon, for example, trade, as a focus point. By changing the focus, this teaching practice can give a more accurate insight into how everyday life was experienced.

This teaching practice encourages looking and reserving space for certain social groups which are often underrepresented. For example, women, children, and minorities. It should be noted that this approach will thus need a slight reorganisation of the material you already have. School textbooks don't always have all of these perspectives, in which case a University textbook may be more useful.

The teaching practice utilises maps to demonstrate how a factor such as trade influences different people across national borders. Questions can be asked such as: How and why trade existed between cities/peoples. As well as how trade might have caused internal and external migrations of people.

DIARY ENTRIES

One activity within this is for students to create a diary entry, imagining themselves in the shoes of another person, perhaps living in a different area and in a different era. The family should include at least one man, a woman, and a child, to represent varying perspectives of daily life. There are however limitations, for example, not all religions can be represented in one family. This activity encourages students to think about what everyday life would have been like for each family member. What occupied their thoughts, what worries did they have, what were the main activities of their day?

Take for an example a story about a Chinese family living and trading over the Silk Road. As travel over the Silk Road becomes more and more dangerous, they may consider moving elsewhere or seeking other job opportunities. Perhaps a family member comes to visit and gives another perspective. Maybe the family thinks about what they hear from other countries e.g. Mongols. Doubts can also be expressed: What are the worries of the people who stay behind?

HOW TO ASSESS THE STUDENT'S WORK:

There are various options for this and teachers are invited to choose (or pick & mix) the one that is most suited to their class and circumstance:

- Presentations of the maps

- Learning phases

- Exam with shorter exercises such as a Kahoot quiz

USEFUL TIPS:

How to solve the problem of curricula constraints?

- Don't go into too much depth

- Be selective in chosen topics

- Not interesting topics at end of the year and most important at the start

How to adapt to students of different ages and writing abilities? Jan recommends that for:

- Grade 5 and 6- students need to write a lot. Thus this best practice can be tailored to be less about history and more as a trigger to get students writing. Students can then present in class the text they wrote- another added skill to be practiced.

- Grade 7 to 10- older and more independent students can have greater flexibility and use role-play and theatre. For the project element, students can have the choice in making; photographs, posters, and (SRP) scenes.

A tip from Jan himself: Good readers often do well in history classes, whilst those who struggle typically do less well. However, the content is not necessarily the problem, but the assessment method could play a huge role. Jan suggests for example to change the format from a typical written exam to a more practical format, for example, to create a poster or a short video.

ADVANTAGES:

- Opportunity to enhance understanding of the other/3rd person perspective

- Covers often overlooked topics in history education, such as women, children, and migrants.

- It focuses on a personal history that deals with everyday life.

- Not nation-specific. The practice can easily be transferred to teachers from various geological backgrounds.

- Low cost, as it does not require a large investment. Maps can usually be sourced free of charge or very cheaply. Illustrators and artists will require an expense but can be seen as an ‘optional extra’.

- The Best Practice does not necessarily require advanced technological equipment.

- The teaching practice can be conducted both online and offline.

LIMITATIONS:

- The level of educational materials could perhaps be too complex for students of younger ages to read and understand.

- Resources must be made available, maps must be created prior to the lesson by the educator.

- As the topics covered are usually not mainstream, perhaps slightly more time and effort is needed to research and discover these often unheard voices.

CONCLUSION:

Jan's future plans for the teaching practice: to continue with the silk road as a personal project. Next year Jan will transition to University where he will do a Ph.D. focussing on the effects of digital media on learning outcomes in handling texts in history class.

You can contact Jan at: jan.siefert@uni-due.de

To find examples of maps, stories, and worksheets, please see the files attached. Please note these are all in German but do still provide an idea of how the teaching practice can be realised.

Below are a number of resources for acquiring maps and getting into contact with artists/illustrators:

- Vector maps

- Worldwide maps database (in German)

- SAP scenes

- akg-images (database for photos, not too expensive and very fast)

- artstation.com (looking for other artists, many of them are for hire)

- Pauline Wisp (Artist)

* The information presented in this blog post is extracted from an interview between Jan Siefert, Birgit Gӧbel, and Adriana Fuertes Palomares as part of the Critical History project and the collection of teaching practices on Global dimensions of national history and postcolonial history, and which took place on October 13, 2021, in an online format.

The collection of teaching practices for the Critical History project is realised with co-funding of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union.

The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Teachers’ Guide on Effective Online and Blended Learning

Learning history through folk songs – the case of Seto Leelo

The European Experience: A Multi-Perspective History of Modern Europe, 1500-2000

The European Experience: A Multi-Perspective History of Modern Europe, [...]

RETOPEA- A project to promote religious peace and tolerance through history

God is back! Although we live in a largely secular [...]

IT Learning Environments in Estonia