In connection with its Critical History project, EuroClio interviewed professionals from several countries to gather teaching practices that allow students to gain historical insight through heritage.

This practice has been collected through interviews with art historian Tiina-Mall Kreem at Tallinn’s Kadriorg Art Museum, and Madli-Maria Naulainen, history teacher from the Estonian island of Saaremaa. They presented us with an original and connected approach to the study of historical heritage.

A baroque origin: from museums to classrooms

Their teaching method draws on the work of the 17th century baroque sculptor Christian Ackermann. The team was involved in a research project on baroque art with the Estonian Academy of Art. Finding the character of Ackermann interesting, they decided to use the story of his life and work to appeal to students – teaching them not only baroque art, but crucially about the era in which he lived and worked in Reval (Tallinn).

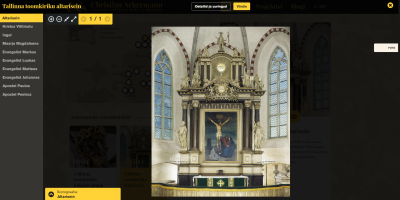

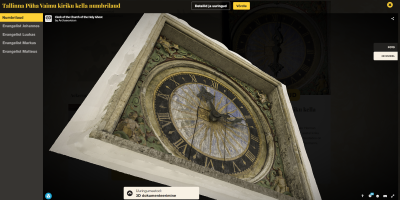

To do this, a website (in Estonian and English, www.ackermann.ee) was created tracing the life of this Baltic German through his various masterpieces, spread throughout the country. In addition to this, there is a separate website (in Estonian only, https://ackermannidigitund.ekm.ee/) with accompanying tasks and questions for students, as well as instructions for the teacher.

Christian Ackermann: A woodcarver’s insights into Estonian society in the early modern period

On the website, which aims to bring artistic and historical heritage into classrooms, history teachers can find a real gateway to introduce their students to the complexity of the 17th century. For example, Christian Ackermann’s sculptures tell us about the religiosity of the period: drawing from her experience with pupils, Tiina-Mall noticed how youngsters had difficulties to imagine the importance of Christianity in 17th century Estonia. Using this collection of retables, altars and crosses created by the craftsman, and digitised in very high definition, she can now summon specific examples to demonstrate the piety of the era, in the same way a museum curator would.

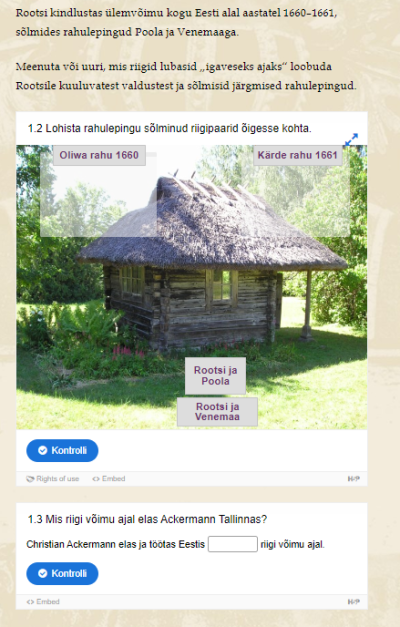

The website has been designed to be a complete experience even without the teacher’s interpretation, linking specific works of art to various levels of historical knowledge. Some exercises reveal what daily life would have been like for Ackermann’s contemporaries; their clothes, habits and everyday trivialities. Others help to explore the structure of early modern society through the guilds that still existed during Ackermann’s time, or indeed the power relations in the Baltic region – including the position of Estonia within the Swedish Empire at the time as well as its place in the larger European context.

The question of minorities and the past in Estonia

The choice of words is important on the website: ‘’the most scandalous and talented wood carver of Estonia’s baroque era’’ is, in many ways, more of a wood carver in Estonia than an Estonian wood carver. The artist happened to be a 17th century Baltic German, living in an ethnically diverse country, consisting of Germans, Jews, Balts, and Slavic peoples living under Swedish rule. Choosing to study Ackermann’s artworks nowadays, when the demographics of Estonia are totally different and Baltic Germans a tiny minority, is a way to address the sensitive past through practical examples. Tiina-Mall and Madli-Maria consider the study of cultural heritage pieces to be essential in order to explain the complexity of this past.

An case of digital exploration

Tiina-Mall conveyed the idea that this kind of digital teaching can help grab the attention of students to topics that they would otherwise quickly lose interest in. Using interactive activities involving smartphones for educational purposes can indeed help to bring a sense of concreteness to a learning experience. The two teachers highlighted that they witnessed a lot of excitement with the kind of interactive activities and digital exploration, with teachers asking questions and students answering directly on their devices. The digital aspects serve another purpose of course: not every town or village in Estonia will have an Ackermann piece to admire in person. As such, designing an online platform allows for a more inclusive learning experience for students who would not be able to travel to Tallinn.

This cleverly arranged site shows us how cultural heritage and history can be used in duo: a bottom-up approach from national heritage expanded to wider historical issues, while highlighting the local and the global interconnectedness. Ackermann was from Estonia, but he was also German. He lived in the Swedish Empire and produced art of the global movement that was the baroque, now visible locally in Tallinn and other areas of Estonia.

Of course, a website, even the best designed in the world, cannot completely replace the experience of a physical museum or heritage site. But Madli-Maria is rather confident that with the 3D images of the artworks ‘’you have the type of experience of being there yourself’’ affording her students on Saaremaa island an opportunity they otherwise would not have.

Teaching with digital heritage platforms

The teaching material made available on the website is divided into three parts: World view, city life, and cultural heritage. The platform also includes a glossary that aids students and teachers alike with terminology of the era. The platform allows students to drag and drop images to sort them, answering questions either with text or by ticking off boxes, among other tools and features. The exercises for students give immediate feedback and allow students to try over again if they do not get the right answer.

The educators estimate that completing the entire platform will require at least three hours for students. However, in their experience teachers will pick and choose the most interesting exercises for their own students.

The exercises largely fit with the Estonian curriculum of 7th and 8th grade (basic compulsory school), as well as 10th and 11th grade (upper secondary or high school) and have thus been developed for students with this age range in mind. A particularity of the Estonian educational system is that students often take classes on art history before they study history. The materials are therefore also used in art history classes. The educational system also strongly encourages interdisciplinary blending of subjects and the materials have been used also in science classes where the restoration work of old objects is emphasised.

“I wish that my students will open their eyes and see the value of these items”

– Tiina-Mall Kreem

Opportunities to adapt this best practice and its limits

The particular historical content of the Ackermann project is not necessarily transferable to classrooms elsewhere in Europe, but the idea of building a wide-ranging set of lesson plans and exercises around a personality like him should resonate with educators elsewhere.

This kind of learning materials and method is a testimony of the massive investments of the Estonian state in the ‘’digital revolution’’. In the educational sector, Estonia prides itself for its digital learning environment: Madli-Maria and Tiina-Mall created lots of resources using https://sisuloome.e-koolikott.ee, a website commissioned by the Ministry of Education for teachers to create online activities. While Estonian students may have access to better equipment and are more accustomed to working in the digital sphere than students in many other European countries, the Ackermann project contains innovative solutions and lessons to be learnt. Ackermann.ee was created with funding from Estonian’s heritage protection fund and this has obviously ensured high quality and professionalism. The platform contains highly detailed imagery, including 3D models. The platform with questions for students, on the other hand, was created on WordPress and is certainly not beyond the reach of teachers with some level of tech-savviness.

A concern remains however on how long such modern materials can last, as webpages can be outdated within a few years. Keeping students engaged through digital innovation thus also has its pitfalls, which both Estonian educators highlighted.

This text was written by Andreas Holtberget on the basis of a conversation between Madli-Maria Naulainen, teacher on Saaremaa, Tiina-Mall Kreem of Kadriorg Art Museum with Andreas Holtberget and Nathan Receveur (both EuroClio) as part of the Critical History project and the collection of best teaching practices on heritage education. This was conducted as part of the collection of teaching practices for the Critical History project with co-funding of the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Union.

The European Commission’s support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Helping all student answer challenging questions about the causes of historical events and developments

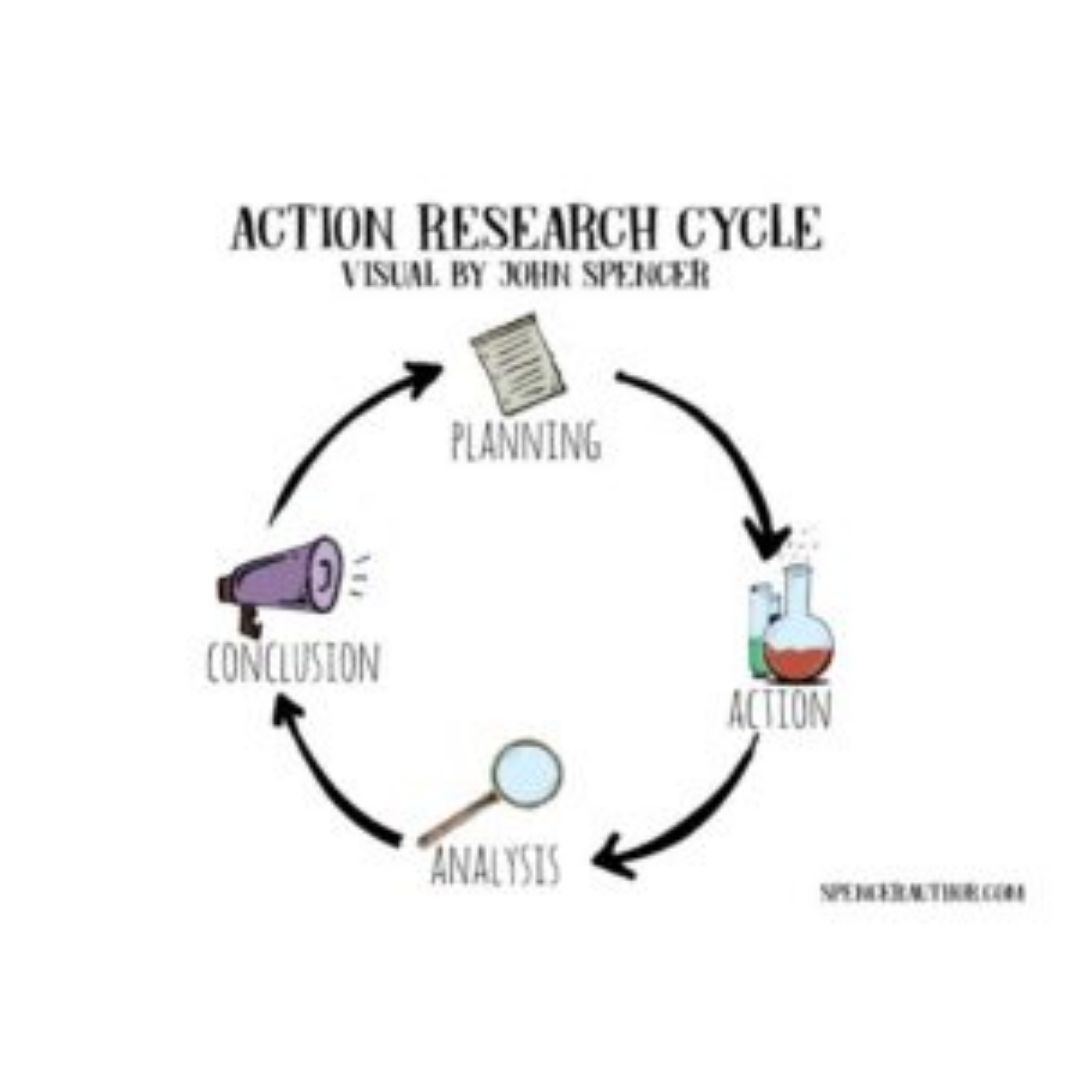

Action Research: projects as active methods to develop civic skills

How do we decide what we believe? – Helping students learn how to question beliefs and test claims to become more (self) critical and evidence based in their thinking

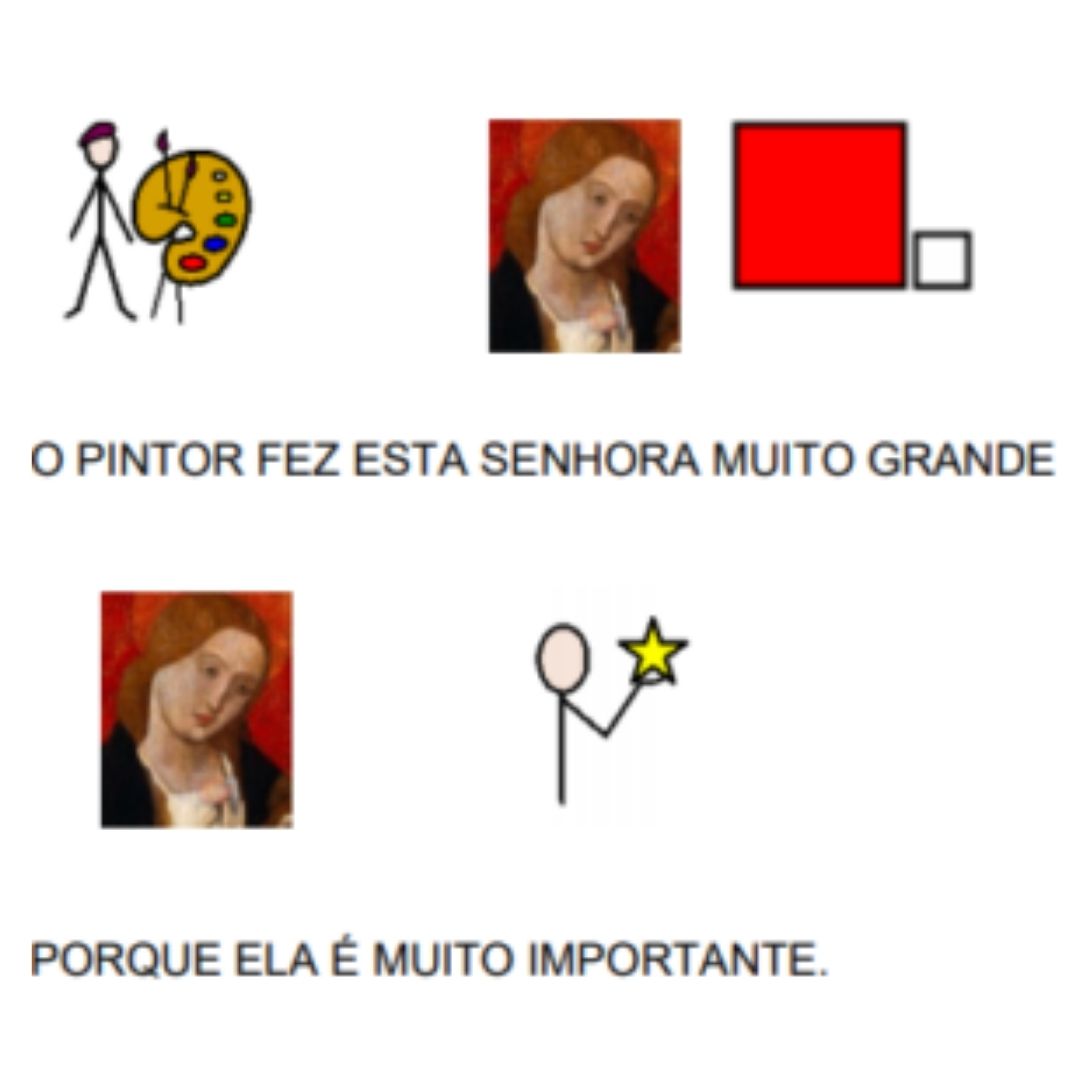

Augmentative Communication: the creation of visual vocabularies as a support in the study of works of art

The Other, The Different, The Identical