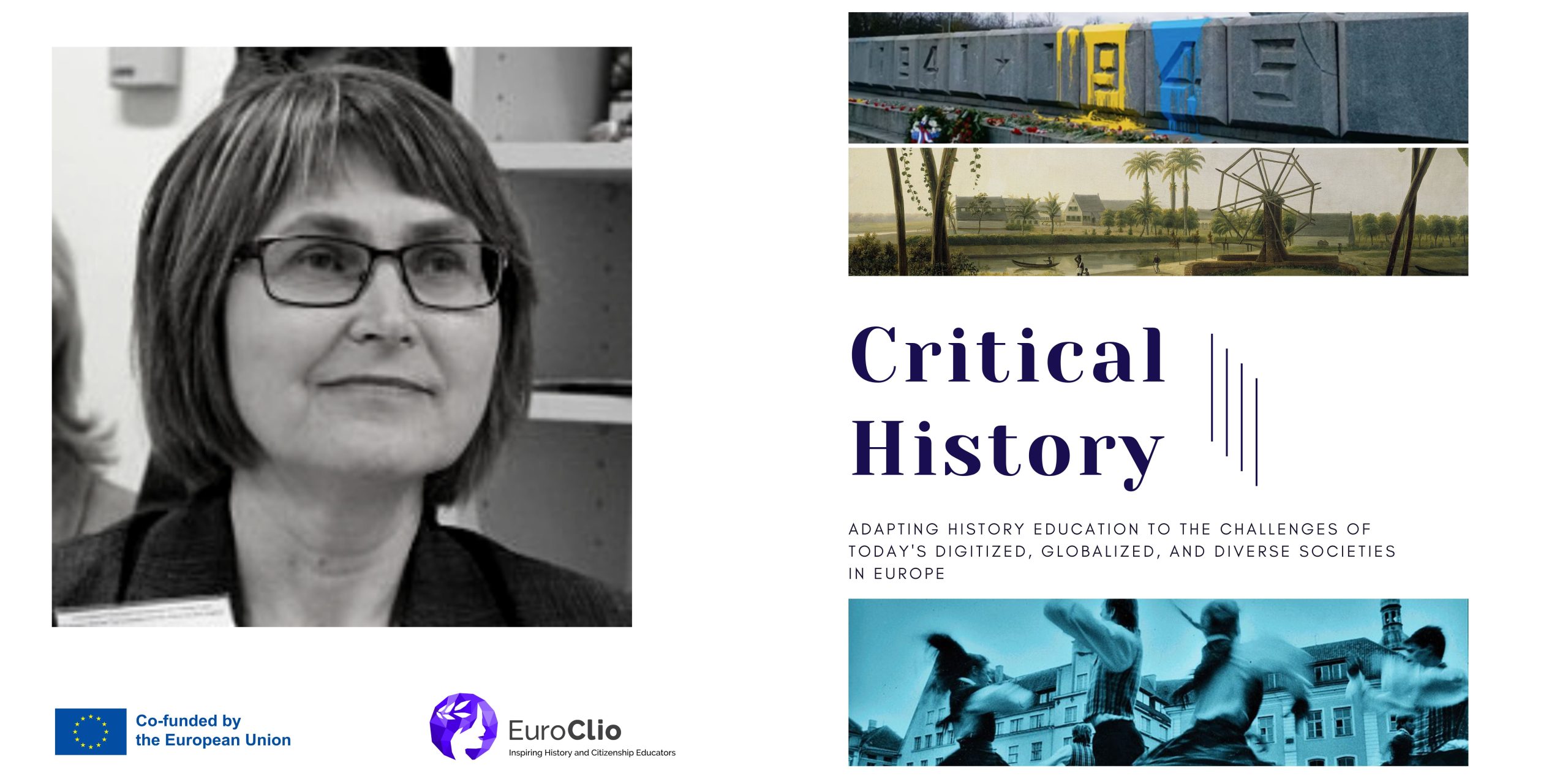

Critical History is a project led by Dr. Mare Oja of Tallinn University in Estonia. Having worked together on the project with colleagues from the universities of Augsburg, Salamanca and Wroclaw as well as EuroClio over the past three years, Dr Oja reflects on the project results and how it can contribute by addressing some of the challenges facing history education today.

The main project outcome has been the publication of a Study Guide (in English, Estonian, German, Spanish and Polish) highlighting four topics in history teaching: heritage, the role and influence of the internet, global perspectives on national history, and public history. The key target audience are students at teacher trainer colleges as well as in practice teachers. The Study Guide also feature several teaching practice examples collected by through EuroClio’s network.

Mare Oja: Critical history is a very wide topic. It’s about how we are approaching history, what does it mean, how we are looking to history, how we are looking back to the past. We have to think critically, while taking account of the conditions of the situation, the period, the time we are looking at.

The main aim is to show that history is not just one narrative as it is written in the textbook

Thinking about history teaching specifically, in many cases history teaching mean that the teachers are just transmitting one narrative from the textbook. The main aim is to show that history is not just one narrative as it is written in the textbook, but there are several aspects which should be taken account of. Students should think more about how we know history, what we can explain based on sources, and what is influencing our understanding and explanation of sources. Critical history is to think about the past or to look back to the past critically.

EuroClio: What do you see as the key challenges for history education today? Including specifically for teacher training?

The main challenge is to make history meaningful for our students today, by trying make a link between the local context they find themselves in with more abstract and bigger problems and events in the world

Dr Mare Oja (third from left) with Adam Dargiewicz, Dorota Wisniewska, Joanna Wojdon and Andreas Holtberget (left to right) at a Critical History project meeting in The Hague, June 2023

MO: Students complain that history is boring. Because in many cases they have to study one narrative, a lot of dates, a lot of names. They do not see the link with the history they are studying. The main challenge is to make history meaningful for our students today, by trying make a link between the local context they find themselves in with more abstract and bigger problems and events in the world. And to show that they are also part of the history. History is happening every day, every moment with them.

We also need to think with them about the past, on the base of continuity, reason and consequences and so on. And what I see in Estonia is that our teachers are not always making history meaningful. They are just taking one paragraph [from the textbook] today and the next one tomorrow. They are focusing only on stories. And stories are also okay. It does not mean that you cannot tell stories, but you have to make a personal link to motivate students, showing how they can use everything they are studying, seeing the links between the past and the present.

EuroClio: In the study guide that we made for Critical History, you are the lead author for the part on heritage and history education. What role can and should heritage play in history teaching?

MO: Heritage is all around us in the society we are living in. In many cases, school history is very orientated towards political history, but to make personal links we have to start with the familiar. In the fifth grade, for example, when we are starting with history in Estonia, we are starting with different sources where students have to think about what sort of sources they have and can find at home or where they live. And if we would like to concentrate on human society and culture, then we have to use heritage to explain the past, rather than just looking at political issues. Of course, policy and war, diplomacy, changing maps, political maps, etc. is important too. But it’s much more the heritage that they are living during their lives, and this is very good to link this to explain history through heritage and then also to make them to appreciate all the heritage surrounding them. To think about the old customs, testimonies and so on. Helping them to interpret today’s society on the base of that of the past.

EuroClio: Do you have any good examples of how heritage can be used in that sense of bringing history closer to the students and making it more meaningful?

MO: We did a project with Estonian teachers, 75 authors in total, and we made different books for every county of Estonia, as well as Tallinn and Tartu. Using the frame of chronology of history, we tried to find local examples and aspects that can explain the various periods in the best possible way.

Making use of something local, which students know the best, and from there they can then link more easily with much wider aspects as well

And it can be a very good starting point. Making use of something local, which students know the best, and from there they can then link more easily with much wider aspects as well.

EuroClio: The Critical History Study Guide is touching on three other subjects in addition to heritage, namely internet in history education, global dimensions of national history, and public history. How do you think heritage education could benefit from these other approaches? And what are the links between them?

MO: I think that heritage is linked with all these subjects. With public history – well, they are using heritage because heritage is in museums as well. They might be doing both tangible and intangible heritage.

And of course, then there is IT and technology. It can be linked with heritage approaches in several ways. First, it can be the possibility to go somewhere you cannot go physically. For example, we have a lot of art in our museums. And people from countryside schools need two hours to drive somewhere and then two hours back – it is too expensive and takes too much time, and if we have collections made available via the internet, it is a great opportunity. And of course, we can go even further. We can go to American or French museums!

The second is that heritage is now digitised or digitising. A lot of newspapers, a lot of sources. [Here in Estonia], we have very good contacts with archives, and we have archive lessons and archive pedagogy. Students can go to the archives and study there, but they can also do this through video lessons using digital sources.

The third is digital reproductions. We can recreate old environments and use reactions to bring students “back to the past”. I think we will see more options in the future. [The technology] is helping us to “move” in time and space.

EuroClio: Thank you very much, Dr Oja, for this talk.

Critical History: Adapting history education to the challenges of today’s digitized, globalized, and diverse societies in Europe is an Erasmus+ Project (2020-1-EE01-KA201-077997) of the European Union. It is led by Tallinn University together with the universities of Salamanca, Augsburg and Wroclaw as well as EuroClio.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.