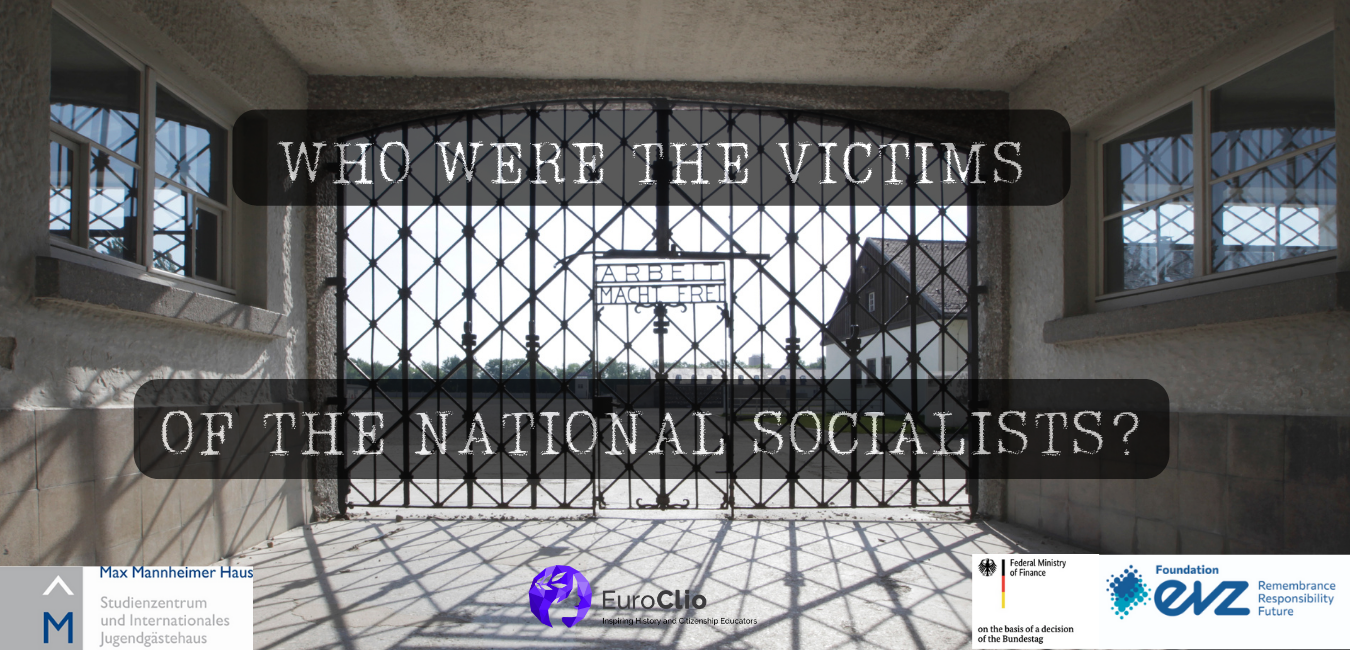

As part of the project “Who Were the Victims of the National Socialists?”, former EuroClio trainee Evangeline Procopoudis conducted virtual interviews with three of our team members from Denmark, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Slovakia.

In our final instalment this week, we talk to Matej Beláček, who is a teacher in Bratislava and a member of Team Slovakia together with his colleague, Tatiana Bírešová.

To begin, could you briefly introduce yourself?

My name is Matej Beláček and I am a history teacher at a bilingual high school in Bratislava. I was supervising a group of fifteen students in this project. We also cooperated with Trebišov High School, where three of their students participated in the project. I’ve been teaching for five years now. I studied history here in Bratislava and have lived most of my life here.

What does the typical history curriculum look like in Slovakia, and how is this project different?

The curriculum for teaching history, especially in high school, has become a lot more flexible than it used to be. There are some objectives that we are supposed to teach students. There are three years of two mandatory history lessons a week in high school, which is a general education program. The teachers are able to adjust a lot of the curriculum according to the objectives. At our school, before I started here, they [had] already [organised] a field trip to Kraków and Auschwitz which [took] three days, and a visit to the National Holocaust Museum in Slovakia. So we covered this topic in our school, I would say, more than we are required to.

But this project was a chance for motivated students to go deeper and find out more about the Jewish community in Bratislava, as there [were] synagogues in Trebišov and Bratislava that are no longer standing. This was a connection for our two schools. The students were from three different years, and many of them did it as an extra credit assignment. Some of them did it just for their interest and their passion, and some did it instead of a test for their history class. For half of them, it was connected to what they were covering in their history classes, but it was an extension to what they learned in the classroom. For the younger students, they were obviously interested in the topic, they were able to research more information and create this digital map and work on it together – [it was] not just them receiving the information, but actually analysing it. I think they appreciated it, and from what I’ve been discussing with them, all of the younger students were really glad that they joined the projects. They learned not only about the Jewish community, but the history of our city, and they were able to work on their skills. It gave them something more than just working on a history project.

How were students selected to take part in this project?

I just gave the information for anyone who was interested to join, and I suggested to some students that they could do this for extra credit or instead of a test. They were supposed to sign up by themselves and we had an introductory session. We discussed their motivations and expectations, as well as what they were supposed to do, study and create. I think it was a process – at first, they were sceptical about how to cope with an extra activity [on top of] what we have to study for our classes. But in the end, all of them appreciated the project, because it was something they found interest in.

Could you walk us through your school’s Local History Project?

After I gave the information for the students to sign up, we had an introductory session at the end of March. Then, we slowly decided to show the students around. I took them to a museum on Jewish culture in Bratislava, they had a lecture on Jewish culture with a historian, they were taken to the National Holocaust Museum, and also, because they worked in three teams, we had some team sessions where they would discuss how they would split the project and divide the roles amongst themselves. So that was the process in April and the beginning of May. We already had a timeline for the creation and presentation of the project in May, and they were supposed to present it in the last week of May. On 27 May, they presented their project to the whole school, and the week before, they were already uploading what they had created. Some of the students worked with a digital map and described who the person or victim was, and they took photographs and attached it to the information they [found]. One team also worked on a video on Jewish people in Bratislava.

The last week of May was the most intense because they were already finalising their work, and I had to go through their work with them and comment on it and try to have it in the final version. Then, when they presented it, [the project video producer] Aaron came [to Bratislava], and the Trebišov students also came and did a video as part of the presentation of the project. Our students could see how both schools cooperated on this project. The three Trebišov students and three of my students worked with Aaron over three days around Bratislava and created a video tutorial. The group that was working on the video tutorial was a particularly passionate group that enjoyed working with Aaron – they were very grateful to be part of the project.

From a teacher’s perspective, do you think place-based learning can be applied to other subjects? Was it easy to fit into the school curriculum?

The school curriculum for history is not the greatest problem. The greatest problem is the schedule. There were students from different classes and groups, so to take them somewhere for a couple of hours was almost impossible – and that was the greatest challenge. Place-based learning is a really great way to approach the students with the material and with history topics. This is off-topic, but I took my homeroom class to a castle nearby, and we discussed it since it has stood there since the early Middle Ages. We talked about the different roles of the castle over the years, and when they could see that it used to be a church in different centuries, they were all very interested to see how that had changed. It is a very good way to get the students interested in anything, and it works great with the curriculum in Slovakia as students are supposed to understand and analyse our history [together] with European history. When we did the project about the Jewish community in Bratislava, they could really feel and understand it better through place-based learning.

Thank you for answering all my questions, is there anything you’d like to add that I may have missed?

Our approach was more free, and I let the students [follow] their interest and sign up. For me, that was the most important part – I don’t like to be the teacher who [gives directions] and tells students what to do because I don’t see the point. I am actually implementing this project in an elective class with our senior group next year. I also am thankful that [Project Advisor] Nadine Docktor gave me some materials and ideas [during our first project meeting in April 2022] in Dachau, and I already have many topics and material to work with in the next years to do projects in the classroom who elect history as their extra lesson.

From the beginning, I wanted this to be a student project, I wanted their initiative to come through. I think it’s important for them to learn from their own mistakes and create their own work. I am grateful for this project because it was an opportunity to [spark] the interest of students who may not have been interested at all. I have one student who struggled in the first term and almost failed history, and now she got an A at the end, just thanks to this project. She told me that she was so glad that there had been this opportunity because she really struggled with taking tests. Tests are not good for all the students, so this project was an opportunity to do something else. The agency of the young people, which was one of the goals of the project, reached this objective.

Interview conducted by Evangeline Procopoudis