From early youth, Europeans are brought up with celebrations and commemorations of the past. Monuments and ceremonies paint the way they look at the world. In a world in which international contact increases alongside new nationalist tendencies, it seems more important than ever to look critically at the ways we commemorate. What cultures of memory do exist? Are there alternatives? Is there a ‘best’ way of remembering? How should we remember in the future? A youth exchange sought to address and answer these questions.

In early May of this year, pretty much as soon as international gatherings were allowed again, a group of youngsters from all over Europe gathered in Leusden, the Netherlands. They attended a youth exchange, organised by YMCA Netherlands, with support from the Roots for Peace Programme of YMCA Europe. The project was made possible with support from the Erasmus+ programme of the European Commission.

The exchange aimed at bringing young people from all over Europe to the Soviet Cemetery in Leusden, The Netherlands. There, they would discuss the importance and need for memory in order to shape a better, more peaceful world today. To do this youngsters were invited to various commemoration- and remembrance-related events that the Dutch early May has to offer. The main aim was to not only raise awareness of remembrance and memory, but also learn to think critically about the need and value of these.

Past, present and future

To reflect this aim the exchange was named Then, Now and Later, Together Towards A Composite Memory. ‘Together’ referred to the great diversity of participants that, either physically or digitally, participated in this project. Participants had their roots in Scotland, Ireland (both the republic and Northern Ireland), the Netherlands, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Germany, Georgia, France, Kosovo and Canada. ‘Composite Memory’ refers to the wish to look across the borders and find what connects youth from all participating countries.

The youth exchange followed a structure reflected in its name. The six-day exchange encompassed three days focusing on the past, two on the present, partially through hybrid means, and one on the future. Youth from participating countries were challenged to do this in three ways:

- Immersion in multiple workshops, tours, games and presentations aimed at exploring personal and national histories.

- Conversation through various guided conversations/ brainstorms aimed at disarming participants (‘breaking the ice’) and put their personal opinions to the test. This sought to strengthen their personal development and critical thinking.

- Participation in various commemoration events, including a Flower Placing Ceremony at the Soviet Cemetery (May 3rd), the Dutch Remembrance of the Death (May 4th) and Dutch Liberation day festivities (May 5th), bringing them into contact with multiple ways of treating the past.

How do we look at the past?

Involving youth in some really specific commemorative events, for example the remembrance of Soviet soldiers in the Netherlands, led the youngsters to think about the commemorative traditions in their own countries. Youth were asked to compare the traditions they had participated in during this youth exchange with the traditions they grew up with. Participants presented their nations’ commemorative traditions and were asked to analyse these with attention to detail: whom is the ceremony aimed for? Who attends? Is the subject matter focused on events on the past, or do they address the present? Are speeches given, and if so, by whom? Is there a special role for politicians? Elderly? Youth? The military? In the end they answered questions that tested their values: what is a respectful way of commemorating? What is the best way of addressing conflicts, both those of the past AND the present?

Many participants never had to live through war and conflict. Yet all had a separate emotional connection to it: Scottish, French and Dutch participants that had no immediate memory of conflict, but knew about it from the stories from their families, their friends and fellow-students. Many struggled to place themselves in a world that is torn apart by conflict: ‘’how can I help to make the world a better place?’’ Participants from Georgia, Ukraine and Ireland had faced conflict and violence and found an open space to share their experiences in.

Remembering in the present: youth from all over Europe helped preparing and laying flowers at soldiers’ graves at the Soviet Cemetery of Leusden, the Netherlands

Confronting conflicts of the present

At the background of this project laid the war in Ukraine, which commenced when the organisation of the youth exchange was in full swing. It was decided to have the physical exchange continue and invite participants from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus participate digitally. Participants from all over Europe were welcomed in a hybrid setting to join a new series of digital workshops and lectures. It was sought to keep the exchange open for participants from all sides of the conflict. This led to a small number of Russian and Ukrainian participants to be also present at the physical exchange in the Netherlands, next to receiving a group of digital participants from those countries. The digital programming did include discussions and attention for the conflict in Ukraine, mirroring it to conflicts to the past and asking what it means to be a victim, a refugee, an accomplice and a bystander.

Digital programming also sought to find connection. A workshop from a Russian art historian from the State University of Moscow, for example, invited each and every participant to fill a ‘museum of childhood’ with memories of one’s childhood years. It appeared that many shared a personal history of candy, backyards, favourite pets and childhood games. This connected people from different parts of Europe with objects and stories that show that, despite all differences, we all remain human.

The Present: digital contact with youth in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia

The diversity of countries brought different stories to the table and each participant had their own memories to offer. Conversations ranged from grandparents’ stories, to participants’ confessions of their own histories, sometimes involving drug and alcohol abuse. Stories of the Georgian War in 2008 were told and listened to with as much respect as stories of personal loss and tragedy. Equally, the lingering sectarianism in Ireland and poverty in rural Scotland were addressed. A safe-yet-open space for discussion allowed participants to share the memories that were most personal to them, transcending the conflicts of the past and creating a bridge to the present.

A future to live for

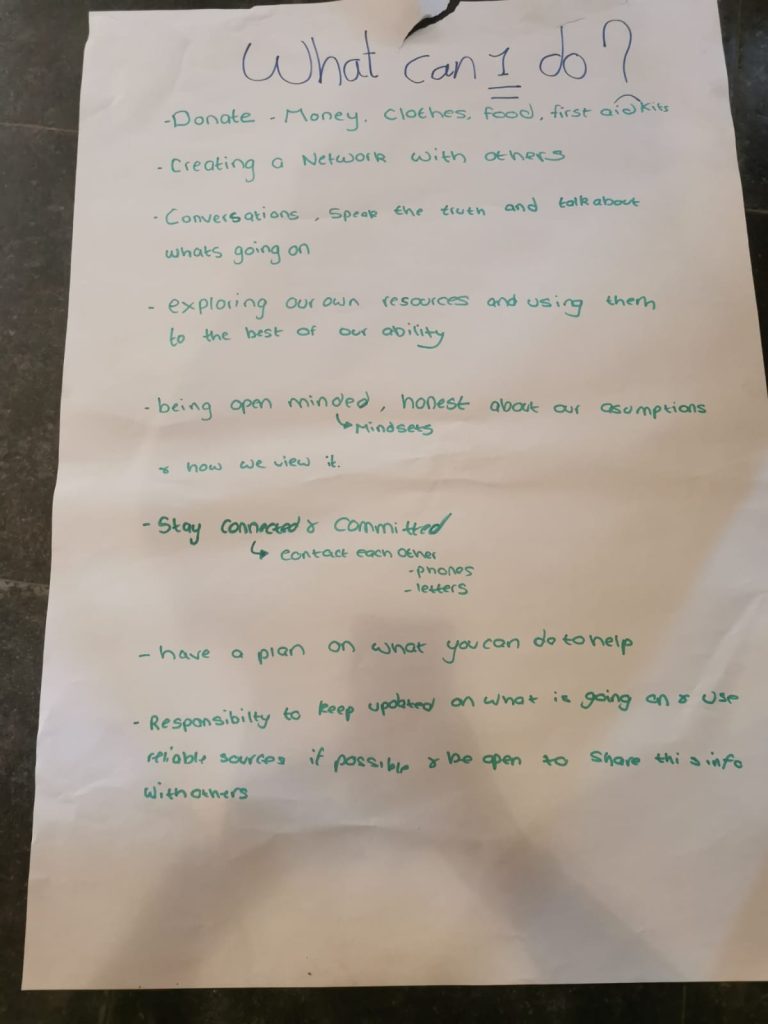

And what about the future? How to create a bridge to what has not yet taken place? The future confronts us with the most pressing issues of today. Youngsters discussed their own roles in a future. How will they remember conflicts of past and present? How will they share stories with their own children? And grandchildren? And what can they do in the immediate future? What can they do in response to the ongoing war in Ukraine? Discussions like these were held in groups of European youth, that by now had become friends.

Facilitating contact between youth from different communities and different backgrounds is a rewarding challenge. In the course of days, youth that is seemingly at odds did connect and fraternise over the central theme of commemoration. They enjoyed moments of fun and games but also took part in serious discussions and actively challenged their own beliefs. Maybe most important of all was that youth was enabled to come together to share their own stories and memories. To exchange stories with people from other backgrounds and learning that they are very similar to your own stories than you could possibly have anticipated! The immersing, conversing and participating may have brought the youngsters together in an atmosphere of openness, but the socialising and group-bonding tied all youngsters together in a shared story: a composite memory indeed!

The Soviet Cemetery of Leusden has its own education programmes. You can find more information on these at: https://sovjet-ereveld.nl/education/?lang=en

Want to know more? Send an e-mail to jonathan@ymca.nl

The Future: creative ways of addressing conflict

The Future: the result of the brainstorm in response to the war in Ukraine