From the beginning of EuroClio, I was confronted with the pitfalls of writing national narratives. I met colleagues in countries where they had just begun writing more or less complete new narratives, but also places where existing national narratives were under constant pressure due to political debates or certain lobby groups. Greece belonged to the latter group of countries. I remember a lecture of a young Greek scholar, who explained how difficult it had been, and still was, to write a coherent national history based on a heroic classical and pagan past and a modern Christian present. I also remember how an attempt in 2007 to present a new school textbook became global news as the Greek Orthodox Church considered it ‘too soft on the Ottoman empire’. Finally, Greek EuroClio colleagues continue to argue regularly for a more coherent national narrative within local schools.

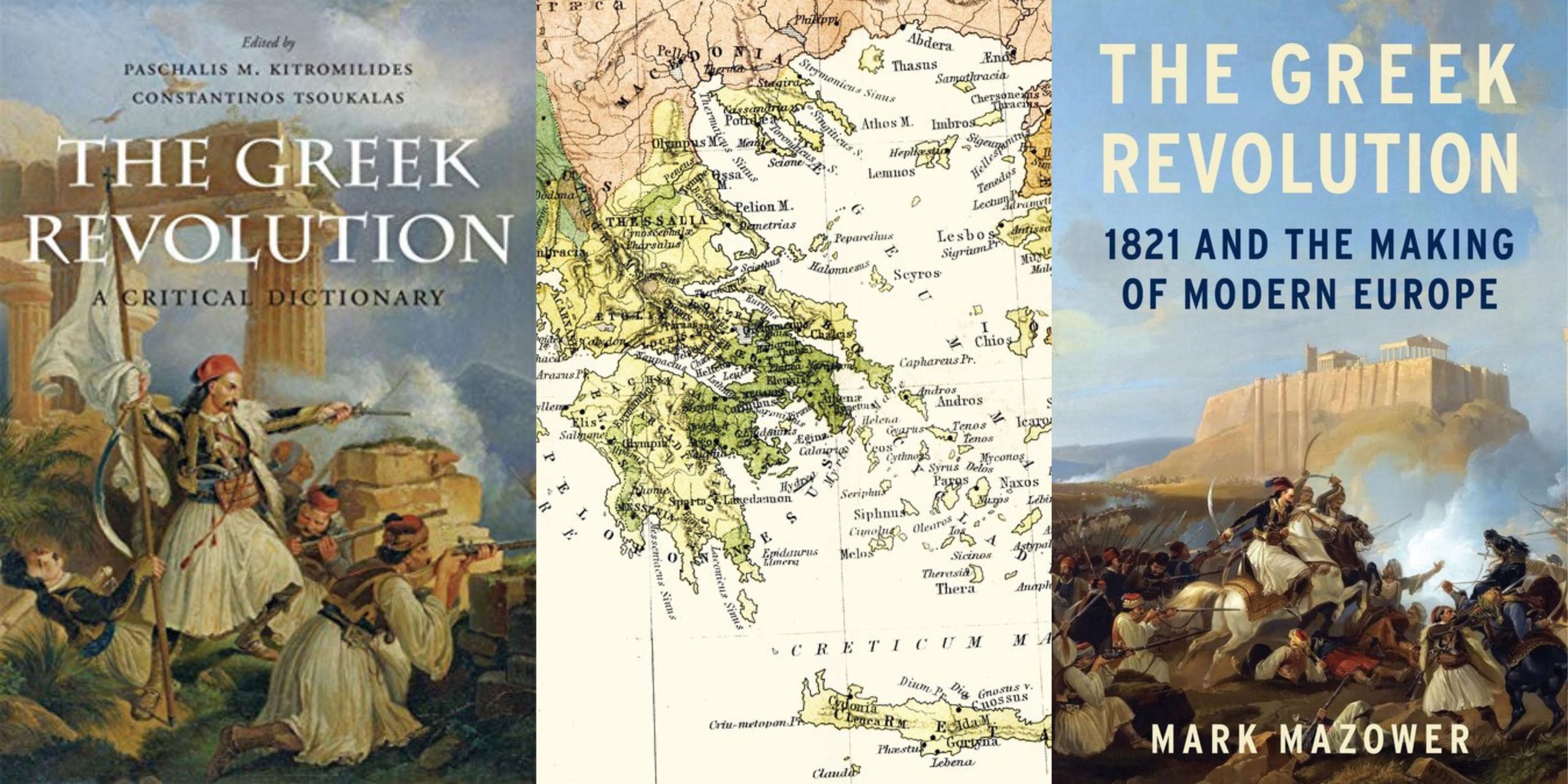

2021 was the 200th anniversary of the beginning of the Greek War for Independence (1821–1830). Arguably an appropriate moment for a historiographical reflection on this crucial event, which certainly fits in the age of revolutions and was in many ways also an outcome of the Napoleonic wars. Two important publications saw light in 2021 and both address in detail the events of this period: The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary by Paschalis M. Kitromilides and Constantinos Tsoukalas (Editors) and The Greek Revolution, 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe by Mark Mazower (both 500 + pages).

I was intrigued to find out how the historians involved would critically review the almost mythical proportions of this Greek fight for freedom. Reading the foreword of the Critical Dictionary I became hesitant as it rather aggressively asked the reader who ‘would dispute that contemporary Greece forms, by virtue of its modern origins, part of the West’. However, the more than 30 articles give an incredible insight into the complexity of the story of this revolution against the Ottoman Sultan. An impressive selection of Greek and international contributors analyse the revolution and its regional and transnational repercussions. The publication has a thematic approach that gives insights into the role of local and international personalities, institutions, events and places, and ideas. The last chapter looks at how events were interpreted in the press, art, literature, and music and evaluates the impact of intellectual movements such as philhellenism and the Enlightenment. The articles are obviously largely representing the Greek narrative; it would have been a strength if some articles would have looked a bit further into the greater geopolitical dimension. After all, that dimension was in the end decisive for obtaining independence.

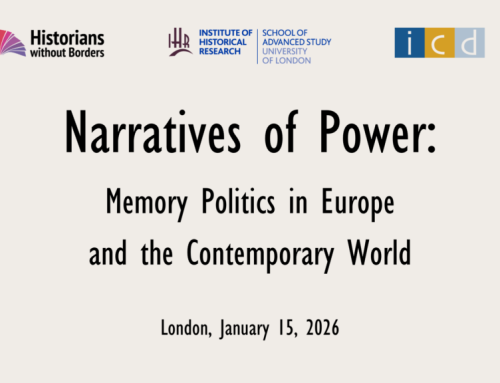

The English/American historian Mark Mazower, who began his career as a historian of Greece and the Balkans, took on a rather classical chronological narrative of the complex events, which took place in very different places in contemporary Greece. He considers them at first ‘not so much a single war as a set of interconnected regional conflicts’. Mazower presents the story with many details about Greek and Ottoman warfare, different military and political leaders, hungry townspeople, and suffering women and children. It is a substantiated critical review of the traditional struggle for Greek independence as many of the leaders were more focused on their self-interests rather than on the common goal of national freedom. The worldwide dimension is widely present, looking into international combatants as well as relief actions and geopolitical decision making.

What I missed in both publications was a serious focus on the position of the many other communities in the region such as Albanians, Turks, and Slavic people. Here a clear source problem became apparent, as the Albanians are especially positioned in their traditionally described role as (Ottoman) fighters and rogues. Modern Turkish research would have been helpful to give better insights from their perspective on the events. Even the position of the many Greeks who remained in the Ottoman Empire after Greek independence is hardly addressed.

The excellent last chapter in Mazower’s book, Love, Concord and Brotherhood, brought me back to the earlier question of how to write a coherent Greek national narrative, as it closely reviews how slowly and with difficulty the Greek authorities, post-independence, were connecting the many actors and visions into one centralised state. I came to wonder how much of the revolutionary diversity of 1821 still impacts present day Greece. Writing a sound and inclusive Greek national narrative will continue to be a challenge, but these books are certainly important new building blocks.

Reviewed and written by Joke van der Leeuw-Roord, EuroClio Founder and Special Adviser

The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary by Paschalis M. Kitromilides and Constantinos Tsoukalas (Editors). Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press (March 25, 2021), 800 pages, available on amazon.nl for 37€.

The Greek Revolution, 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe by Mark Mazower. Penguin Books Ltd (UK); 1st edition (4 November 2021), 573 pages, available on amazon.nl for 28,99€.