Based on the Webinar Series: Using Historiana to Teach History from Different Angles

Session 3: “Paintings of Everyday Life” – Hosted by Ute Ackermann Boeros

History lessons are often dominated by the stories of nation-states and governments, of wars and conquests, of kings, generals, dictators, and other political leaders. Compared to these ‘important’ figures, the ordinary people have been receiving much less attention, as most historical narratives tend to push them to the background to prioritise those ‘at the top’. Departing from this approach, our webinar session sought to give spotlight to the common people – the peasants, the workers, their families and children, among others. We explored their ordinary lives through an ‘unconventional’ historical resource: Genre Art – the paintings of everyday life.

Traditionally, historians have not often used artworks as historical sources, but mainly as illustrations, for example in textbooks or lectures. However, this webinar has shown us how art can play the role of a great source material for history teaching and learning. The webinar, hosted by Ute Ackermann Boeros on March 22, 2022, is the third out of four sessions of the webinar series “Using Historiana to Teach History from Different Angles”. Drawing upon the Historiana collection of genre paintings, our host brought to discussion an exciting question: “How can we use Genre Art effectively in history lessons?”

Ute began the session by engaging the audience with some examples of genre paintings. She presented, for example, the artwork “Preparing for Dinner” by Frederick Daniel Hardy, and asked us to brainstorm on how this painting could potentially be used in a history classroom. Many fascinating ideas were raised by enthusiastic participants. An Estonian teacher, for instance, proposed that we could contrast this bright-coloured picture of domestic life with textual records, for oftentimes the latter might describe a much grimmer story of poverty than the former. Another suggestion, raised by a teacher from the US, was to use the painting to explore the depiction of women’s roles.

Image 1. Preparing for Dinner, 1854, by Frederick Daniel Hardy (1827-1911)

A teacher from Iceland, in addition, remarked that the work also provided a glimpse into pre-industrial lives, hence could be used to help students reflect on the changes brought by the Industrial Revolution. Ute followed up the heated discussion with her ideas, drawing attention to the portrayal of different generations (the old woman beside the spinning wheel, versus the middle-age mother and the young girl in the kitchen) as well as to material culture – that is, what kind of clothings were worn by people of that era, or what kind of utensils they used for cooking and producing,…. Indeed, art can help us compare between lives in the past and the present, which gives us insights into small – often overlooked – historical changes.

Art consists of many things – including images, monuments, music, and written sources such as poems – which can be used in the classroom as primary sources. Among them, as mentioned above, the potential of paintings as historical sources has yet to be fully harnessed by historians and history teachers. Apart from serving as illustrations, these visual materials can help to develop among students a ‘feeling’ for a historical period, and equip them with historical thinking – the skills to describe, analyse, evaluate, and construct historical interpretations based on primary sources. Ute acknowledged, however, that to make use of art in history lessons, teachers would have to collect information about various aspects of the artworks, such as the artists, the social contexts, as well as artistic conventions – which can be a challenging task that takes up time in an already busy schedule.

Nonetheless, by using the example of Genre Art, the host soon informed participants of the ways in which visual aids could serve as an effective tool in history teaching. Through the pictorial representation of everyday life, students can firstly be provided with knowledge about the lives of ordinary people, who have been largely neglected in most historical narratives. They can furthermore gain understanding about social divisions, as well as past cultures and civilisations, thereby being able to imagine the past more vividly. Genre paintings can also be treated as historical evidence – as eyewitness accounts of certain historical events. However, an important thing for teachers and students to keep in mind is that artworks are not always realistic, but can also be a product of imagination and romanticisation.

For this reason, Ute drew attention to the ‘pitfalls’ (Peter Burke) of using art as historical sources. Like any other primary sources, the origin, purpose, authenticity, and content of the artworks need to be carefully appraised. Teachers not only need to take into account artistic conventions, but should also be aware of the fact that art in general, and paintings in particular, represent the artist’s personal view and interpretation of historical phenomena. Therefore, “knowing your artist” – researching their social backgrounds, interests, motives, and purposes – would be a crucial step in using art effectively to teach history. It is also important to assess the reliability of the sources, for some artworks might have been created with propagandic intentions, or might have portrayed prejudices and stereotypes.

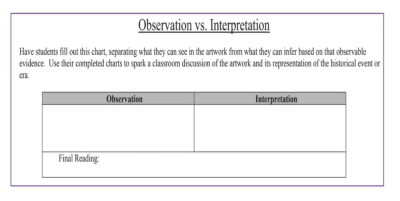

Ute then introduced a teaching method to be used for Genre paintings: the “Learning To Look” strategy, which juxtaposes ‘observations’ against ‘interpretations’ to arrive at a ‘final reading’ (Smithosonian).  She applied the strategy to a number of examples, including the painting ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’ (c. 1763-1766) by Joseph Wright of Derby. Here, one can observe that a philosopher is using the orrery to demonstrate the mechanism of the solar system, surrounded by not only fellow scholars but also children, whose faces are illuminated by the lamp at the centre of the clockwork model. Placing these observations against the historical context of the painting – the Enlightenment era in eighteenth-century Europe – teachers can ask students to interpret, for example, what might have been the meanings of the fascinated children, the stark contrast between light and darkness, and the central position of the orrery in the picture. Simple questions such as ‘when do you think the event in the painting took place?’ or ‘why do you think the artist has made this painting?’ can help to stir up the class discussion. Through this method, the artwork can be effectively used in history lessons to explain Enlightenment ideas to students, as well as to teach them source analysis skills and the ability to make inferences – which can certainly be applied to other types of historical sources beyond visual materials.

She applied the strategy to a number of examples, including the painting ‘A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery’ (c. 1763-1766) by Joseph Wright of Derby. Here, one can observe that a philosopher is using the orrery to demonstrate the mechanism of the solar system, surrounded by not only fellow scholars but also children, whose faces are illuminated by the lamp at the centre of the clockwork model. Placing these observations against the historical context of the painting – the Enlightenment era in eighteenth-century Europe – teachers can ask students to interpret, for example, what might have been the meanings of the fascinated children, the stark contrast between light and darkness, and the central position of the orrery in the picture. Simple questions such as ‘when do you think the event in the painting took place?’ or ‘why do you think the artist has made this painting?’ can help to stir up the class discussion. Through this method, the artwork can be effectively used in history lessons to explain Enlightenment ideas to students, as well as to teach them source analysis skills and the ability to make inferences – which can certainly be applied to other types of historical sources beyond visual materials.

Image 2. A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery, c. 1763-1766, by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797)

Ute concluded the webinar with a reflection session, in which she asked us what might be the obstacles in bringing art into history lessons. Among the replies, one teacher considered herself as the greatest obstacle, expressing her worry about her lack of expertise in art analysis. However, warm responses from other participants assured her that teaching history using an unconventional source like art does not need to be a burden. It can be an exciting journey, where teachers not only give but also receive new knowledge, new perspectives, and new creative ideas from their students. “I have yet to know much about this artwork, what can we learn about it together?” – teachers can engage with the class in this way. Together with the students, they can conquer the unknown and learn along the way.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Historical Association. Image Exercises. Accessed March 12, 2022.

Burke, Peter. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Image as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2019.

Pratt, Ivy. History Painting: An Art Genre or the Manipulation of Truth?. Art and Object, November 2, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.artandobject.com/news/history-painting-art-genre-or-manipulation-truth.

Rabb, Theodore K. and Jonathan Brown. “The Evidence of Art: Images and Meaning in History.”The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17, no. 1 (Summer 1986): 1-6.

Smithsonian American Art Museum. “History and Social Studies Teacher Resources.” Integrating Social Studies and Visual Arts. Accessed March 12, 2022.

https://americanart.si.edu/education/k-12/resources/social-studies.

Suh, Yonghee. “Past Looking: Using Arts as Historical Evidence in Teaching History.”Social Studies Research and Practice 8, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 135-159.

________

This blog post is written by Phạm Thùy Dung on the basis of Ute Ackermann Boeros’ online session: “Paintings of Everyday Life.”

All images used are provided by the Europeana source collection by way of Historiana.

The recorded session of this webinar will soon be available on our YouTube channel!

Our next instalment of the series is taking place on the 24th of May! Bridget Martin will host a session on “Railways and Connectivity”. You can register on our website under this link: https://bit.ly/3K6Jo4b.