An Interview with Dr. Laura Vas

Conducted by Cora Serbser

Dr. Laura Vas is the Head of Social Studies and an IB History teacher at the American International School of Budapest, as well as an IB Diploma Programme examiner and workshop leader for IBDP History. With teaching experience across North America and Europe, she is dedicated to creating engaging and rigorous learning experiences that promote both academic excellence and personal growth. As a department head, she has led curriculum alignment initiatives, supported deeper conceptual understanding across grades, and promoted skill development. Laura is particularly passionate about facilitating thoughtful debates on methodology, removing barriers to learning, conducting action research, and creating classrooms with high expectations paired with strong support. Laura has published teaching materials with AERO, EuroClio, and the IB, and has presented at educational conferences on topics such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and data-informed decision-making.

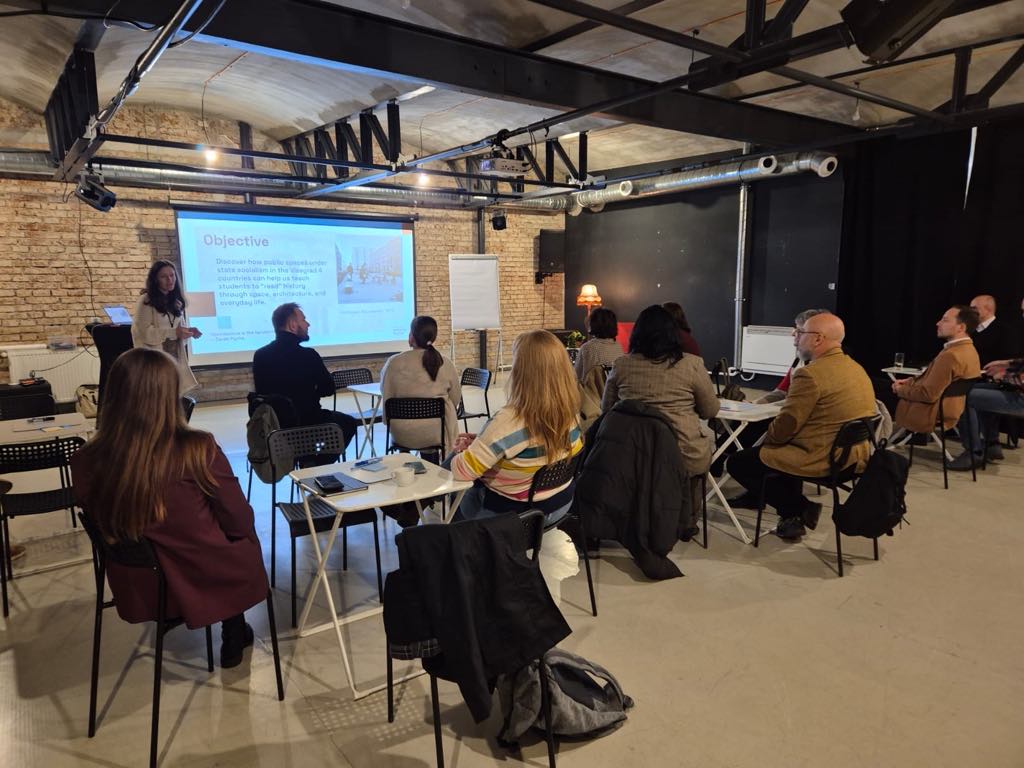

Laura Vas became involved with the Making Visegrad Histories Digital (MVHD) project after coming across a EuroClio call for participants. Having long used EuroClio resources in her teaching, she was drawn to the opportunity to collaborate with historians and educators from across Central Europe to make complex historical topics accessible to international audiences. Having joined us at the Košice Autumn School, Laura sat down with EuroClio trainee Cora Serbser to talk about her involvement in the project and her workshop, “Constructing Community: Residential Spaces in Communist Societies.”

Cora Serbser: Could you tell me about the workshop you led, “Constructing Community: Residential Spaces in Communist Societies”?

Dr. Laura Vas: I chose this topic because I have a background in architectural history and a strong interest in how built environments reflect societies and ideologies. That interest naturally led me to this particular group. I worked with a historian, Čeněk Pýcha, whose research focuses on public spaces and residential architecture — including monuments and memorial practices — and with an experienced History teacher, Mária Harmaňošová. Together, we developed three modules. A key question for us was how to make this topic accessible to a broad audience, especially young students for whom the communist period feels increasingly distant, often even beyond their parents’ lived experience. I wanted to identify resources that would make the subject engaging and relatable. I became particularly fascinated by the theme of children in public spaces: what did childhood look like in communist societies? Where were children meant to play? How much freedom did they have? What kinds of control existed? I collected a range of visual and textual sources — photographs of playgrounds, children’s textbooks from the 1960s and 1970s that conveyed both academic content and social values, as well as depictions of new housing developments such as prefabricated panel buildings and rural houses known as Kádár cubes in Hungary. Viewing these materials through a child’s eyes allowed me to find entry points that would resonate with today’s students. We then built activities around these sources — photographs, visuals, and newspaper excerpts — and encouraged students to interview people who had lived in these environments, effectively taking on the role of historians themselves. That was my main contribution to the project.

Cora Serbser: Your surroundings are so shaped by history, and they, in turn, shape your identity — yet this is often overlooked.

Dr. Laura Vas: Absolutely. We discussed this a great deal. Young people rarely have agency over where they live; those decisions are made for them. Only as adults do people typically gain the privilege of moving as their own decision or purchasing property. For students, therefore, it is important to connect the topic to their own experience of public and private spaces. By starting from a conceptual level — how they perceive their own environments — we can help them recognize both the differences and the parallels between their lives today and those of children in the 1960s or 1970s.

Cora Serbser: When you have integrated this topic into your classroom, how have students responded?

Dr. Laura Vas: I have found that lessons framed around the perspective of children or young people in society elicit much stronger engagement. I teach high school students, so when we discuss themes like music, leisure, protest, youth groups, or education, the buy-in is far greater than when we focus solely on government decisions. Of course, government policies shape those experiences, but when students can connect the material to their own lives, our conversations become more meaningful. Relevance is key — there must be a bridge between their world and the historical world, yet it is equally important, I believe, to expose them to something different and unfamiliar.

Cora Serbser: Why do you think it is important to teach this unit in schools?

Dr. Laura Vas: Teachers, particularly in public systems but even in independent schools, have to follow a prescribed standardized curriculum, leaving little space to explore everyday life or public-space topics like these. However, history lessons often give space to some flexibility. Even a small portion of a lesson — a short “activator” at the beginning or a brief integration within an existing topic — can open space for curiosity and connection. In every module we developed, my co-author Mária Harmaňošová and I aimed to make the material engaging and accessible to young people. These are not niche topics; they are windows into how societies functioned and how ordinary people lived.

Cora Serbser: Were there challenges when teaching this unit? Sometimes parents, for example, might have memories or perspectives that differ from what students learn in school.

Dr. Laura Vas: Yes, that can be a challenge. With visual sources, there is a risk of flattening cultural differences — if context is missing, the material can become oversimplified or generalized. Striking the right balance is essential: enough context for understanding, but not so much that it overwhelms. For example, we might analyze a film scene showing a young couple moving into a prefabricated apartment block, celebrating their new home. Students might not find that lifestyle appealing, but by establishing context — the optimism and sense of progress of the time — we help them appreciate that emotional reality. If this groundwork is laid before students discuss such topics with their parents, it can prevent misunderstandings and open more constructive conversations. In that way, parents feel included rather than contradicted, and students gain perspective.

Cora Serbser: Otherwise, children can feel caught between what they hear at home and what they learn at school, like “children of divorce”.

Dr. Laura Vas: That is a very good point — it can indeed feel like being “between two worlds.” What teachers can do is empower students to ask questions that invite their parents to share their stories. In doing so, students build empathy and develop critical thinking skills at the same time: they learn to see their parents’ experiences as valuable historical sources. This process not only deepens their understanding of history but also strengthens intergenerational relationships. That, I believe, is one of the great gifts of teaching this subject.

Cora Serbser: Have you noticed differing opinions or even conflicts among students when teaching these topics, and how do you handle that as a teacher?

Dr. Laura Vas: I think it is essential to begin by mapping students’ perspectives. I often teach about authoritarian systems — both communist and fascist — and students come to these topics with genuine curiosity. My first step is always to ask what drives their interest and what they hope to understand. Once students engage with a variety of sources and viewpoints, tensions tend to dissipate naturally. I frequently use visible thinking routines to check for shifts in understanding: “What did you think about this system before? How do you see it now?” When students can say, “I used to think it was only this group affected, but now I see the complexity of the situation,” that is the moment of success. If they can recognize that history is never as simple as it might seem, we have achieved something meaningful.