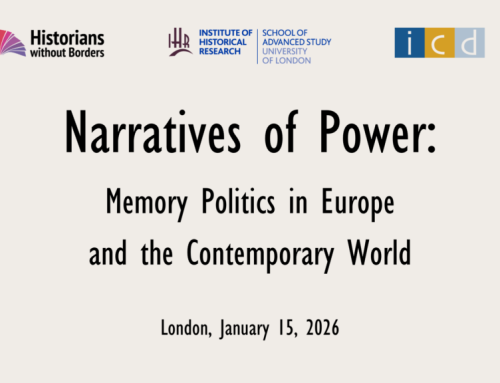

Cover Image: Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung © 2023 Barbara Yelin, Reprodukt.

Interview by Matthias Lukkes

What happens to histories of war, genocide and mass atrocities when historians no longer write about the survivors, but actively work with them? An interview with renowned comic artist Barbara Yelin and Professor Charlotte Schallié on working with survivors in public history, the complexity of human memory, and the power of the graphic novel to capture it.

“Do you take sugar?” Emmie Arbel asks Barbara Yelin while having coffee in Emmie’s living room in Tiv’On, Israel. “No thanks, just milk.” “Me neither”, Emmie responds, “but I always put the sugar box on the table. With its spoon. It is from her. I have nothing else that belongs to my mother. She used to move it, and now I move it. Just this spoon…nothing else.” As Emmie turns the spoon and lights a cigarette, the scene at the coffee table shifts to one panel depicting Emmie as a child with her family out on the street being escorted by a man in Nazi uniform. Though the street is dimly lit, the yellow Star of David pinned on their clothes are clearly visible. One panel, then the scene cuts back to the present time where Emmie sits at the coffee table again.

Image 1: Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung © 2023 Barbara Yelin, Reprodukt.

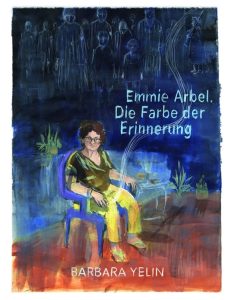

With segments such as these, renowned graphic artist Barbara Yelin makes the impact of the past on the present clearly tangible. The intertwining of past and present forms a central theme in her latest graphic novel Emmie Arbel. The Color of Memory. The graphic novel revolves around the life of Emmie Arbel, who was born in The Hague in 1937 into a Jewish family and spent part of her childhood from November 1942 to April 1945 in several German transit and concentration camps in the Netherlands and Germany. Her experiences of the Holocaust as a child have been featured in the graphic novel But I live, published in 2022 as part of a previous interconnected research project.[1] Unlike its predecessor, The Color of Memory narrates Arbel’s entire life, stressing how life of a child survivor continued after the Holocaust. Impressively, Yelin weaves together a wide range of themes, including life in Israel, motherhood, sexual violence, and the continual impact of childhood memories on later life. As a result, the book is much more than the story of a survivor: it captures life in all its complexity.

The Color of Memory, now available in French and German and released in English next fall, is part of a research project initiated by Germanist and historian Charlotte Schallié. I spoke with Yelin and Schallié during an online interview on a spring evening about this significant book.

Barbara Yelin: “I thought about how I could show the contemporaneous presence of memories, and how the experience of her memories breaks into Emmie’s everyday life. I experienced this while listening to her: we are together, and then suddenly there is a deep memory that comes in.”

How did you figure out how to translate this contemporaneous presence of memories into your drawings?

Yelin: “This is really something I thought about. How tight can I intertwine these layers of time? It was a challenge to do that, because I did not want to explain it by writing: ‘okay, now we go back to 1942’ – the reader needs to experience it.

Part of achieving this was a technique where I had pieces of the panels of the comic like pieces of a puzzle. I would have pieces of her memory in the form of statements she made during conversations, or in the form of historical photographs and documents, and photographs from her now. Then, I would ask myself: how can I combine these pieces, this puzzle of memory?”

Were you piecing the puzzle together in dialogue with Emmie Arbel? Or was this something you did?

Yelin: “I did it, but Emmie had the opportunity to judge it, to correct it, and to respond to it. The entire process consisted of several layers of interaction: I would make a drawing, and then I would ask her: ‘might it have been like this?’, to which she could answer ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘I don’t know’, or even: ‘I know it better than this.’ Then I would weave her answer into the drawing. Emmie was always accurate about the details of her memories, but also very generous to leaving the artistic decisions to me.”

The working method where survivors work closely with the artist is a central pillar of the project Survivor-Centered Visual Narratives, of which Emmie Arbel. The Colour of Memory is one outcome. The project, initiated at the University of Victoria in Canada by Professor Charlotte Schallié, brings artists and survivors together to produce visual narratives on histories of mass atrocities such as the Holocaust, the Yugoslav wars and war and state violence in Syria and Iraq.

Image 2: Barbara Yelin (© 2024 Martin Friedrich) and Charlotte Schallié

What is the rationale behind the working method of this book, and the project as a whole?

Charlotte Schallié: “The project is not just pairing an artist with a survivor to ‘quickly do a story’. It is based on trust building that happens over years – four in the case of Barbara and Emmie. This process is deeply embedded in a commitment to work with the eyewitness over an extended period of time, holding space for everything that may surface as part of this trust-based relationship. Our collaborative research practice challenges us as historians to think more fully about our own responsibility when we elicit memories of suffering from others. The method of visualization as Barbara and Emmie used can be a trauma-informed way to record individual memories, because it allows the survivor to tell what they want to tell when they are in conversation with the artist. A focus on reciprocity and mutual care puts agency back in the person telling the story, centering their voice.”

How did this process of ‘taking responsibility and restoring agency’ work during the project?

Yelin: “It took more time than I expected. It was not just the question: ‘Emmie, what are your memories of the Holocaust?’ – it was a conversation about a whole life. This book could only happen because of our many conversations. Emmie was so generous to give me this time. This was also important because some specific decisions took time with Emmie. Sometimes it took a while before she could say: ‘Okay Barbara, now I know I want to tell this period of my life, because it is part of it’. Or: ‘Barbara, I remembered something more’.

We spoke about many details. Every second month or half a year Emmie would receive a new version of the story board and we would speak about it. This is what makes a drawing a special way to communicate. Drawing is about very specifically looking at things, encouraging you to be mindful and attentive in the moment. When I draw something, new questions about the subject I am drawing at that moment come up. Questions I did not even know I would have before. I gathered these questions, and would ask them to Emmie. With her answers, I renewed my drawing, after which the whole process would repeat itself. This dialogue would result in more questions than she had had before as well.”

You mean that new questions came up with Emmie about her own experiences and memories once you showed her a drawing you made?

Yelin: “Yes. There are questions she and I would not think about before. What was the temperature? What did you wear? Had there been people in the room? Was there a guard? Did you sit on the floor? How many layers did the bed have? Was it dark outside? And of course: what did you feel?”

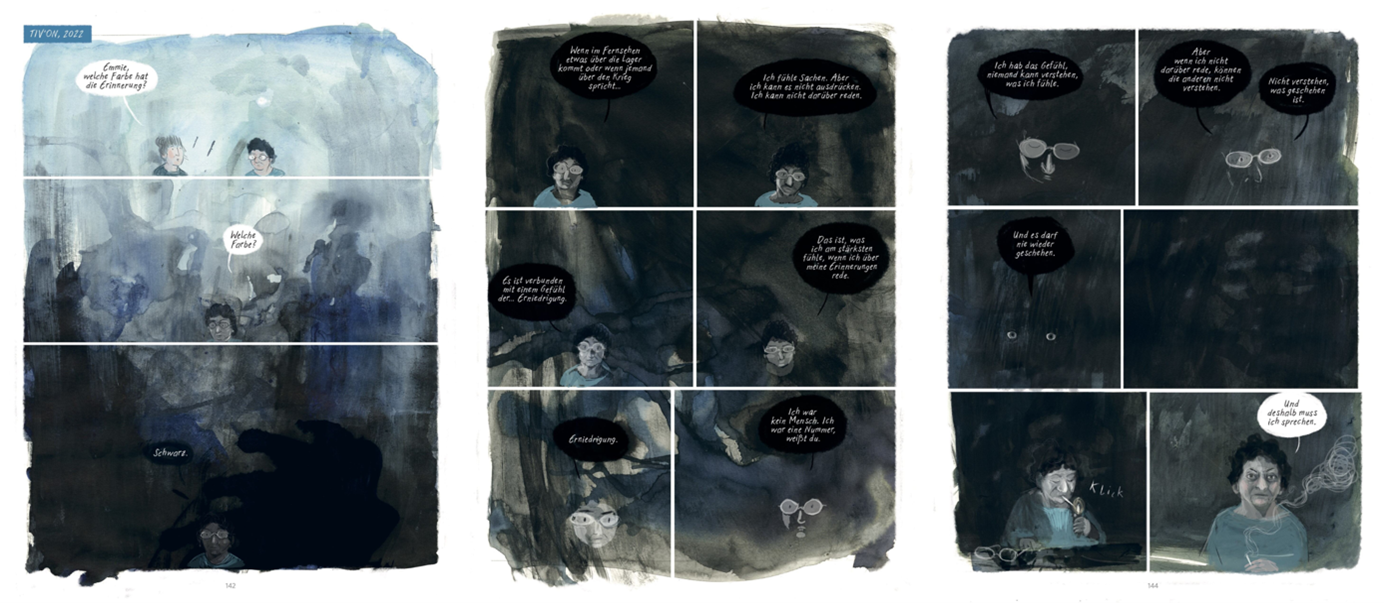

Schallié: “This collaborative, reciprocal process shows how visualization centers the lived experiences of survivors. Emmie has blackouts, bits of experiences she cannot remember, how do you visualize that? In a more traditional oral history testimony, I would not ask, for example: was it dark outside? What did you see? What did you feel? – But these questions prompt memories that in a more scripted or formative interview would not surface. As Barbara said: drawing was necessary for the questions to come up. Because the process of drawing is a tool of critical investigation, it engages with these important questions.”

How has this impacted your idea of the use of graphic novels in public history?

Schallié: “Early on I thought graphic novels would be great for knowledge mobilization, for making the story accessible. But then I realized: wait a minute, creating visual narratives with survivors is in itself a research tool that we should explore much more deeply. You talked about the temporal changes between the here and now in The Color of Memory, but the point of view actually shifts as well: in several sections of the book we see in black textboxes that sometimes it is Emmie as an adult speaking, and then suddenly it is the child speaking, even though it is the grownup version of Emmie whom we see on the page…this is so complex, and so rich for us to think more critically about the fabric of memory.

We should also think about graphic novels as giving the survivor a tool for self-documentation. This means that we return agency to Emmy, creating space for her – with the help of Barbara – to speak about her experiences from the perspective of a small child or a grownup woman.”

Image 3: Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung © 2023 Barbara Yelin, Reprodukt.

Is that what you learned from the project so far?

Schallié: “In Emmie Arbel, but also in the book But I Live the survivors were not reduced to the experience of human suffering. We asked Emmie Arbel, Nico and Rolf Kamp and David Schaffer to choose how they would like to be captured in images, also representing their lives in the here and now. What we owe to the survivors when we truly work with them, not about them, changes the entire research dynamics.”

And yet, contrary to these inspiring outcomes, Barbara, you end the book with an afterword in which you seem somehow disheartened. You write: “…I wanted to find a way to tell this suffering, I wanted to find connections, maybe I wanted, how presumptuous, to find comfort for Emmie, for us. Yet it did not happen…”[2] Why did you decide to end your book on this note?

Yelin: “That is what I felt. What can we do, about the past? I found that there is no answer. What can Emmie do? She can live. Of course, I knew that from the beginning, but maybe I wished somehow that collecting her story, structuring and narrating it, would solve or explain something. That is not the case. As a German who has Nazi-family history, I can learn, I can listen, and I can cry with Emmie, nothing else.”

Schallié: “There is no Wiedergutmachung, there is no Versöhnung, no reconciliation. Even the title But I Live could be misinterpreted to be heroic – it is not. It is actually a matter-of-fact statement: Emmie says: “I remember that I was going to die […] But I live”. If there is any message from Emmie in the book, it is to live well, don’t waste your life.

In this project, we stayed away from creating a heroic narrative, although, oftentimes, there is pressure to do that. We tend to use the past to serve the needs of the present. We need the past to tell us a story – we oftentimes instrumentalize it by using it for contemporary issues, we weaponize it. In a project like this we are very mindful of the power and language of visual propaganda. We say: just let the survivors have their say. Just let them speak, without overburdening them with what we need from them.”

But then what do we have left as readers to take from this story?

Yelin: “I think we get a greater emotional understanding of what listening does, that is the most important thing that I learned. But also learning about the complexity of a life like Emmies, a women’s story with so many aspects that have not been heard. It was very important to us not to make a book only about traumatic memories of suffering, but also about how someone like Emmie dealt with it: how with amazing strength and courage she faced it by starting therapy, speaking with her family, and finding the words. Her strength is part of the story – but it is not a heroic story.”

Schallié: “Yes, Emmie has the right to tell her life story. But I also feel that Emmie Arbel. The Color of Memory and other graphic novels that engage with personal stories of survivors allow us to bear witness to atrocities that are unbearable or impossible for the human soul to process.

From a human rights perspective it is important that these stories are not forgotten. I am careful with the term empathy – what does historical empathy mean? –, but, in a way, we would like to foster empathy in our readership through telling the life stories of Emmie, David, Nico, and Rolf. If, as a result, our readers do not turn away from current human rights abuses, but become active citizens instead, the project is doing its work.”

To conclude, how can a graphic novel help in this?

Schallié: “The graphic art form allows us to slow down the process of reading; it compels us to pay attention, to engage with how we feel. Comics elicit active listening skills and invite us to step out of the role of a passive viewer. Comics, as in Barbara’s story, are selective in what they represent. In order to complete the storyline, we, as readers, therefore need to inject our imagination into it. We ourselves become an active part of the story and the storytelling process. That is what you want: you want somebody to be engaged.”

Image 4: Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung. Reprodukt, 2023.

Biography

Matthias Lukkes studied History (resMA) at Leiden University (Cum Laude). Since 2022, he works for the National Comittee for 4 en 5 May as editor for the journal WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht.

Original Dutch source: Matthias Lukkes, ‘De graphic novel als getuigenis’, WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht: De oorlog getekend, 13:3 (2024). The Dutch digital journal WO2 Onderzoek uitgelicht offers in-depth articles about ongoing and recent research regarding the remembrance and commemoration of World War II and the handling of (un)freedom. The original article can be accessed here.

[1] But I live is part of an earlier research project Narrative Art and Visual Storytelling in Holocaust and Human Rights Education. See also: https://utorontopress.com/9781487526849/but-i-live/.

[2] Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung, Reprodukt 2023, p. 171: ‘Ich wollte eine Möglichkeit finden, dieses Leid zu erzählen, ich wollte Zusammenhänge finden, vielleicht wollte ich, wie vermessen, Trost finden für Emmie, für uns. Und doch ist es nicht geschehen.’