The very early EuroClio years brought me to Weimar, former GDR. I was staying with a family who had a social commitment for that evening and left me with their keys. When I wanted to enter the house, I could not open the door and ended up sitting on the steps of a cold dark stairwell. After a while a woman appeared and invited me in her apartment. It became a memorable evening, where I began to understand the complex situation of the “Ossies”, as the former citizens East Germany were called.

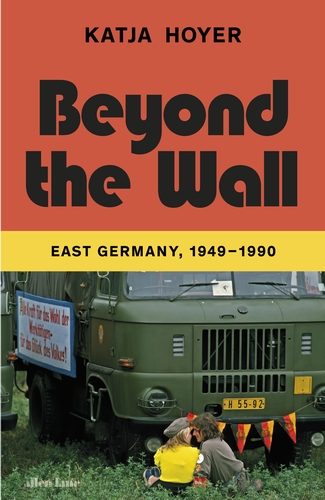

Since then, I have been returning frequently to Germany and particularly to the former GDR regions and was therefore happy to obtain a copy of Beyond the Wall, East Germany, 1949-1990 by the acclaimed Katja Hoyer. The author Katja Hoyer was born in the GDR and was just four years old when the Wall fell. She stayed in the region and was educated as an historian. Ten years ago, she moved to London where she now works as an historian and journalist.

The book tries to tell a kaleidoscopic history of East Germany, claiming to present views from teachers, accountants and factory workers but also from police officers and border guards. Although she uses a lot of short stories about such people, the book is predominantly a political story with a strong focus on the leading men: Ulbricht, Honecker, Mielke – and many more. The GDR was a state lead by strong, sometimes competing, men. Leading women hardly feature, certainly also because they had no voting rights in the Central Committee of the Communist party.

Hoyer begins by telling the story of Ulbricht and others, who fled Germany in the Thirties and who were, under shadowy conditions, also able to survive Stalin’s terror. Others, like Honecker, were victims of the Nazi prosecutions. Initially, these men worked closely with the Russian leadership, but from the beginning they also addressed distinct German issues. They were hardcore communist but, in a way also surprisingly open to the consumer needs of the East Germans.

Hoyer begins by telling the story of Ulbricht and others, who fled Germany in the Thirties and who were, under shadowy conditions, also able to survive Stalin’s terror. Others, like Honecker, were victims of the Nazi prosecutions. Initially, these men worked closely with the Russian leadership, but from the beginning they also addressed distinct German issues. They were hardcore communist but, in a way also surprisingly open to the consumer needs of the East Germans.

The author makes the reader aware of the economic hardships that resulted from the Russian reparation requirements, which had devastating consequences for the rebuilding of the country in the aftermath of the War. The fact that the country hardly had any raw materials on its territory also made sure that it become increasingly dependent on the Soviet Union, especially for oil. It was interesting to read the different financial constructions, which were devised over time to earn money, eventually even with non-communist countries. The political leadership became more and more convinced that they had to satisfy the consumer needs of the GDR population to keep them happy in the socialist state. Unfortunately for them, it was not enough to satisfy everyone, with especially the highly skilled population leaving in droves. By 1961 almost 300,000 per year “haemorrhaged” (the term the author uses) the country by leaving for the West. In a way, building the Berlin Wall was inevitable since as all sorts of services became increasingly limited, useful people were simply packing up and leaving.

The life beyond the wall after 1961 is pictured in a way that the reader becomes aware of the benefits of the state: there was hardly unemployment, housing was cheap and, despite scarcity of materials, increasingly available to everyone. More and more consumer goods were available and there were many cultural events available to the masses. There were good opportunities for education and careers, including for those of worker, or even immigrant, backgrounds. The author especially mentions the opportunities for women to work due to ample child care. Eventually, women were even allowed to join the army, even if leading positions kept being a men’s world. In general, the life was quite pleasant as different interviewees have told the author.

The story of the Stasi, the secret intelligence service, is certainly told. Hoyer uses the concept of “paranoia” of the leadership frequently to explain the enormous budget and the vast number of official and unofficial staff of the organisation. Erich Mielke is pictured as a sinister boss, who is personally involved in spying, not sparing even the most prominent leaders. The author provides numbers of political prisoners and refers to victims of failed escape attempts, as well as deportees. At the same time, she gives the message that if you were clever, you could play the system. Especially pop stars seem to have done quite well. However, I have the feeling that this aspect of the GDR story could have been investigated more profoundly.

In the Eighties it became increasingly clear that the leadership was losing grip. Shortages in high quality consumer goods, the Gorbachev slogans of perestroika and glasnost and lack of democracy created waves of protesters against the GDR policies and its leadership. Without plans to tear down the Wall or the wish to unify the two Germanies, more and more protesters demanded – under the slogan we are the people – change and democracy.

Hoyer gives an exiting account of these last years of the country and give evidence of how fast and unexpected the developments were. Within a few years the GDR had vanished from the map. The book addresses many Western cliches and also make interesting comparisons with developments in West Germany. Hoyer writes in her Epilogue under the title Unity, that we should take the GDR as a part of German history. Personally, I have regularly been arguing that a commonly written post World War German history in the line of EuroClio work carried out in the Balkans or Caucasus would be desirable. We can imagine a similar exercise for the former Warsaw Pact countries, which are now EU Member States. In their case I would suggest starting with their positions in 1918, again following Hoyer when she states that history is continuity and does not have “clean breaks”. Good history writing gives new answers but also asks additional questions. Beyond the Wall certainly does both. A book very much worth reading.

Written by Joke van der Leeuw-Roord, EuroClio Founder and Special Advisor

Katja Hoyer, Beyond the Wall: East Germany, 1949-1990 (2023). Published in English by Allen Lane, 496 p. Available on Amazon from approx. 23 Euro and on Kindle from 11 Euro.