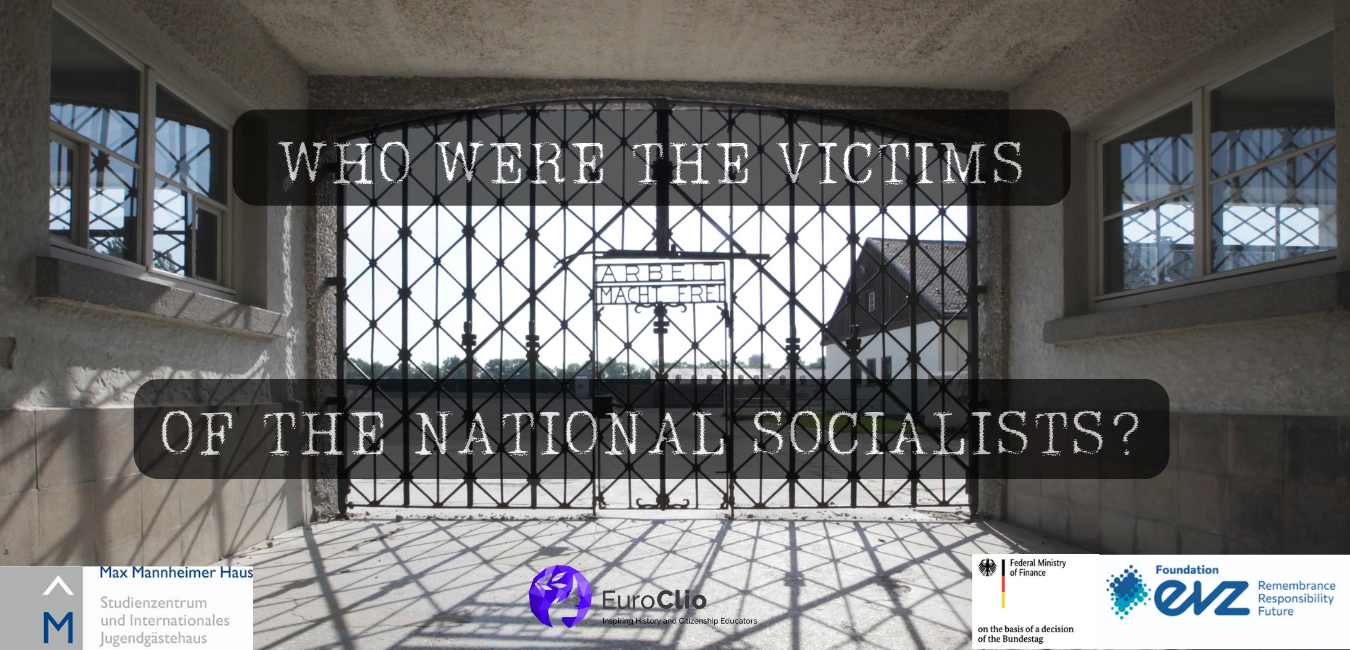

As part of the project “Who Were the Victims of the National Socialists?”, former EuroClio trainee Evangeline Procopoudis conducted virtual interviews with three of our team members from Denmark, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Slovakia.

This week, the interview series continues with Tatjana Jurić, who is a teacher and member of Team Bosnia and Herzegovina, together with her colleague Branka Ljubojević.

Could you briefly introduce yourself and your school?

I am a History and Latin teacher and a teacher trainer. I have been working in the field of education for the last 15 years. I work in a secondary school in Banja Luka, one of the oldest schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is known for achieving great results in many regional and international competitions and projects. Our school was founded in 1895 during Austro-Hungarian rule in our country. It is a big school with more than 1,200 students and 100 teachers. We are one of three schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina offering the International Baccalaureate (IB) programme. We are delighted and honoured to be participating in this project as the only school from Southeast Europe.

With the IB programme, is it a challenge to integrate this project into the existing curriculum?

Our school team consists of students following the national programme and several IB students who are in different grades. Our Local History Project is organised as an extracurricular activity, because in our curriculum, there is no project week or other formal way of including these activities. Culture of remembrance is very important in our educational system, but our project was simply too big and too broad to be organised in regular classes.

Could you walk us through your school’s Local History Project?

During WWII, our city, Banja Luka, was in the Independent State of Croatia, which was led by the Ustaše regime. The Ustaše, formally known as the Croatian Revolutionary Movement, based much of their ideology on Nazi racial laws. Relying on German “theory” about the non-Slavic origins of Croats, they labelled Jews, Roma and other Slavs (especially Serbs) “subhumans”, which created the basis for the persecution and imprisonment of thousands of individuals. Political opponents of the regime, communists, anti-fascists and dissidents were also persecuted. In our city and the area we live in, there are many memorial sites, so we used this unique opportunity to visit several of them for this project. We visited the Jewish cultural centre to learn more about the Jewish community in Banja Luka, the memorial site on Kozara mountain, and the memorial site at Jasenovac, which was one of the largest camps in Europe and was often referred to as “the Auschwitz of the Balkans”. Known for its extremely brutal conditions and large number of victims, this extermination camp was a complex of five sub-camps covering an area of 210 km2. We visited the Roma memorial centre in Uštica and Donja Gradina, the main execution site of the largest Jasenovac camp. We also visited the primary school in Šargovac, one of the suburbs of Banja Luka which was the site of the brutal murder of Serbian schoolchildren. It happened on 7 February 1942, when the Ustaše massacred 2,300 Serbs, including 551 children, in Drakulić, Šargovac, Motike and the Rakovac mine. Place-based learning is not something new in our educational system, and before the pandemic, [such visits were] regularly organised. Students of certain ages would visit one memorial site and pay tribute to the victims.

But what makes this project different is the number of places our students were able to visit and explore, and the methodology used to explore these places and complete their research. The project design was also very well-structured and created a model with which the students could learn about this sensitive and important topic, more than they would learn in any other way. This project is also very important for us because it offers a platform for sharing our local history with the wider public in our country and abroad. Another reason for the importance of this project for our school team is that the genocide of Serbs, the Holocaust and the Roma genocide in the Independent State of Croatia during WWII are not explored enough, certainly not taught in schools and written in history textbooks. We know that stories of these victims should be seen and heard, and we are grateful for the opportunity to share it.

From a teacher’s perspective, was this a project that was easy to put together?

Since we had such huge support from the Project Advisors and Council Members [involved in the project], it was not difficult to plan it and put it together. The other teacher in our team, Branka Ljubojević, and I have a great cooperation. We knew from the very beginning what the framework of the project was, and we had clear guidance through all the steps. Our task was to introduce the topic to the students and create space for them to find out what they would like to further explore and investigate about the victims of National Socialism and the Ustaše movement in our region, and how to present it and share it with an audience. We organised the trips and we made sure that students had everything they needed to do their tasks. I think that the demanding, yet extremely important aspect of the project was to link these past events to the present, and to find the message in it for the present and future – the moral of the story. What do we learn from the life stories of the victims of National Socialism which will make us better humans and enable us to make sure that such horrible crimes don’t happen ever again? How can each of us contribute to the prevention of antisemitism, discrimination, xenophobia and all forms of hatred in our societies? What can ordinary people do in societies where radical, extremist movements develop? How do we treat other people who are different from us? These are just some of the important questions we tried to answer in this project. We learnt a lot from the places we visited, from our emotions, from the primary sources and literature, and from each other.

How have your students enjoyed this project? Any feedback about likes and dislikes?

The students seem to be very satisfied with all the phases of the project. They like place-based learning, the absence of teaching, and the methodology of learning which is different from the ways they usually learn in school. They liked [having] the freedom of choice to explore the themes within this topic. Some of them wanted to investigate the suffering of children in the Independent State of Croatia; others were more interested in the treatment of women, or resistance to Ustaše and Nazi terror in our region. Some of them were keen to provide historical background to the stories they explored, while others were more interested in how to express what they discovered through art. Although it was sometimes emotionally demanding to hear and read about the brutal treatment of innocent victims, I noticed that during the entire process, students honoured them and paid respect to them. The question “How was this humanly possible?” came up when they learned about the horrors of Nazi and Ustaše crimes, which are truly hard to understand, but they managed to focus on the victims and find purpose in paying respect to them.

How were the students for this project selected?

Our school team is very diverse, and we believe that is our advantage. We have IB students and students from the national programme, and we have Serbian Language and Literature teachers and History and Latin teachers. We published an open call for first-, second- and third-grade [students] in the school. We selected students based on their motivation letters, and we believe that was a good way to do it, because the students would need to offer different reasons for why they wanted to participate in the project. Some of them applied because some of their family members were in concentration camps during WWII, while others were very interested in the methodology used in this project. I think that different ages, interests and multidisciplinary approaches just enriched our work, added multiple perspectives, and made it more special. This will be visible in the students’ video about their investigation and in the exhibition, which will open in October 2022 in the city centre of Banja Luka.

Thank you for taking time out of your schedule to sit down with me for this interview!

Thank you!

Interview conducted by Evangeline Procopoudis