In my early days with EuroClio, I travelled widely in the countries of the former Soviet Union. One of my recurring questions was how many Slavic variants or Slavic dialects were spoken in the countries of the Soviet Union. To my surprise the standard answer was always negative, everywhere people seem to have spoken standard Belarusian, Russian or Ukrainian. That astonished me coming from a small country with a large variation in Dutch/Germanic dialects: two A-languages, Dutch and Frisian, one B language., Limburgian, and within all three an enormous variation in dialects and accents.

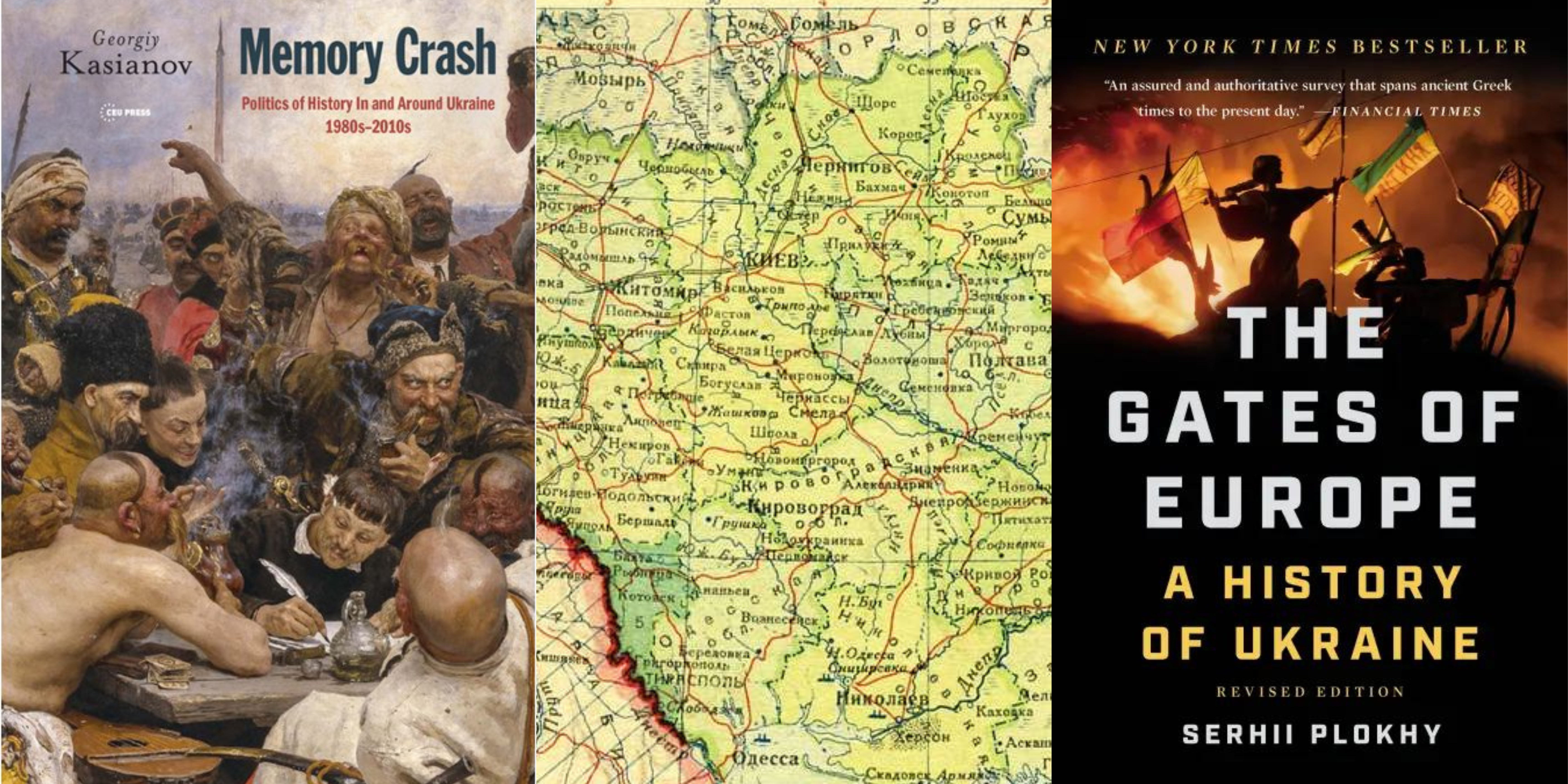

My question popped up again while reading the Gates of Europe, a History of Ukraine written in 2015 by Serhii Plokhy (Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University). I found it highly appropriate background reading to understand today’s horrible war in Ukraine. The book gives a narrative of the wide spectrum of complex events and influences that have shaped current day Ukraine and its relations with its neighbours. Plokhy begins his story more than two thousand years ago, with the origins of the Slavs, and takes us via the Vikings, the Byzantine Empire, the Mongols, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy, The Cossacks, the Russian and Austrian-Habsburg Empires, the post-World War chaos, the Soviet Union, Nazi-Germany and finally to independent Ukraine. He is able to write a coherent narrative addressing the many players, tendencies and forces which together created over 2000 years of history.

However, this is a history which goes far beyond the current borders of Ukraine; it is a history of Central/Eastern Europe that was the playing field for many actors who were interested in the rich spoils of this region, and thought they could claim its ownership. This battle for ownership is significant as it determines up till today the clash regarding the history of Ukraine. In the current war we all have seen how Putin misused the past many times to justify his actions and to manipulate the Russian population into believing that he is fighting for the right outcome. However, other politicians and historians in the region also show a tendency with the same motives to claim absolute truth for their ‘national’ narratives. Ukrainian scholar Georgiy Kasianov gives in Memory Crash, The Politics of History in and around Ukraine 1980s–2010s, written in 2018, a saddening account of how history was used by Ukrainian presidents, national and local politicians and authorities, and historians to argue for their righteous interpretation of Ukraine’s past. He demonstrates this with a manifold of examples of how, instead of feeling together responsible to create a narrative that accepts the substantial diversity of Ukraine’s past as well as present, they were and are all fighting against each other about the right interpretation of the history of Ukraine. They develop politically motivated (regional) ethno-centric narratives using laws, institutions, publications, monuments, and even stamps and coins. Of course, also school history education is an unresolved battleground for claiming the historical Ukrainian truth.

I read the Gates of Europe with the background memory of the many examples given by Georgiy Kasianov in his publication. It struck me that a very close reading of this publication revealed some of the more problematic elements noticed by Kasianov. Plokhy does not shy away from bold statements. In his narration, Ukrainians seem to have a unified identity already in the Cossack times. Ukrainians are peasants with no nobility, New Russia is in 1790 composed of mainly ethnic Ukrainians, the workers in the 19th century industry in the East are migrated ethnic Russians. The pogroms in Kiev in 1905 can be blamed on gangs of migrant workers, Orthodox zealots or outrights criminals. In this case, as in many others, when the plight of the Ukrainian Jews is mentioned, the ethnicity of the perpetrators is blurred and all these statements are not supported by any evidence.

The initial chapters and the final chapters make for an excellent read but the period between 1500 and independence stem too much from a Ukrainian ethno-centric point of view. The Slavic ethnic diversity pictured is seen through current day border divisions of Poles, Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians but hardly takes into account the many regional Slavic differentiations in the vast area this publication is addressing. It does in a way acknowledge the old tale that there was no big regional variation in dialects and tones. The lack of clear referencing is another weakness of the publication as well as the absence of reference to fundamental source research. However, there is a substantial list of literature of background and further reading.

I noticed in June that Plokhy’s book was massively available in bookshops in the United Kingdom. A good thing as many in Europe and beyond are quite ignorant of the history of Ukraine. A country that, as EuroClio Ambassador Iryna Kostyuk rightly remarked some months ago, is for many not more than a blank spot on the geographical map. I recommend reading it together with Georgiy Kasianov’s Memory Crash, to be aware how you can be manipulated into another national interpretation of the past. Writing complex and inclusive national narratives is always difficult, and it seems almost impossible if it is about Ukraine, a vast territory and country with an extremely multifaceted and often tragic past. Plokhy did his best but was not fully able to avoid the ethno-centric pitfall. But with that element in mind, the publication is a good English language asset for learning to understand Ukraine’s past and present.

Reviewed and written by Joke van der Leeuw-Roord, EuroClio Founder and Special Adviser

Serhii Plokhy, the Gates of Europe, a History of Ukraine (2015). Basic Books; Reprint edition (May 30, 2017). 448 pages. Available for US$19.99 at basicbooks.com

Georgiy Kasianov, Memory Crash, The Politics of History in and around Ukraine 1980s–2010s (2018). Central European University Press (January 28, 2022), 422 pages. Available for US$82 on amazon.com