Despite having “Euro” in the name, EuroClio’s work and interest extends beyond Europe’s borders. In connection with the thematic focus on decolonisation last year, we also looked at developments happening outside of Europe, such as in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. One relatively recent development in Canada is the revised social studies curriculum in the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC), where I am originally from. I volunteered to look further into the developments in BC, and was also fortunate to speak with Dr. Lindsay Gibson, an academic involved in the curriculum’s development. The new curriculum began its rollout in 2015, two years after I graduated high school, which means I never got to experience the new curriculum first hand. It was nonetheless interesting for me personally to look into the current state of affairs in my home province, and reflect a bit on my schooling in BC. In this article, I look to explore why the curriculum changed, what changes were made, and what impact (if any) there has been. Though my research began with looking at the aspects of Indigenous history in the new curriculum, I also found threads of other current debates in history education.

What is Social Studies?

I should begin by offering a quick explanation of “social studies” as a school subject as opposed to “history”. In general, the subject commonly teaches elements of history, geography, and civics, and sometimes other disciplines such as economics, sociology, or anthropology depending on the curriculum. Social studies is a school subject that can be found across North America, though different states and provinces may or may not provide it. In Canada, education is controlled by its provincial or territorial governments, instead of being nationally mandated. In total ten provinces and three territories makeup Canada (an area amounting to twice the size of the European Union) and each province or territory has its own curriculum. Lindsay Gibson notes that “how social studies is defined differs in each”. According to the BC Ministry of Education, “The primary goal of Social Studies education is to give students the knowledge, skills, and competencies to be active, informed citizens who are able to think critically, understand and explain the perspectives of others, make judgments, and communicate ideas effectively.”[1]

While it is inaccurate to simply equate the subject of social studies with history, the aims of the Ministry as outlined above clearly coincide with many goals of history education, particularly the work we try to support here at EuroClio. Furthermore, in social studies courses, history tends to be the largest portion of the content. From my experience, I personally only remember two units in high school social studies courses which were not just simply ‘history’: a unit on world religions in Grade 8 (age 13) and a unit on Canadian government in Grade 11 (age 17). This is not just my personal impression alone though. Criticism exists in Canada over the dominance of history within how social studies is taught. In BC, this became more poignant with the introduction of the new curriculum, which was largely based on academic work relating to the concept of historical thinking. This has resulted in a perceived lack of attention to geography. Glen Thielmann, a BC social studies teacher and teacher educator, noted this criticism on his blog about the curriculum change, adding “in my opinion it was not embedded strongly to begin with.”[2] Therefore, despite not being a pure history curriculum, BC’s new social studies curriculum also should be of interest for those involved in history education.

What to teach, and how to teach it

The rollout of BC’s new social studies curriculum began in 2015, taking a few years, which allowed younger grades to grow into the system while not disrupting older grades. The change in social studies was part of a change for the entire provincial curriculum in BC, covering schooling for students aged 5-18. The new curriculum looked to incorporate three “Core Competencies”: Communication, Thinking, and Personal & Social. These competencies, according to the government website, are “proficiencies that all students need in order to engage in deep, lifelong learning”. A current trend in education is striking a balance between the content and the skills driving the goals of curricula, between what content the students learn in class and what skills they learn that will help them beyond the classroom. In this case, the BC Ministry of Education’s focus on the “Core Competencies” looks to highlight competencies that also include substantive content knowledge through the courses.

Another change is the opening up of choice for content in the course. Unlike many European countries, there are limited standardised exams in BC, which already provides for flexibility in the curriculum content. This move away from provincial examinations was already starting before the curriculum change, and there are currently only BC Provincial exams in Grade 10 and 12 on Literacy and Numeracy.[3]

In the revised curriculum there is a further conscious move towards choice in the curriculum content for social studies. “The feeling was that the content was too prescriptive” as Gibson describes. For the current social studies curriculum, guidelines exist for content with suggested topics but no prescribed events that need to be learned except in a few instances. The BC Ministry of Education’s notes on their website, “The goal of this more open curriculum is to allow teachers to spend more time delving deeper into key topics and focus less on simply rushing through a long list of factual details in an attempt to cover all of the required topics.”

“The goal of this more open curriculum is to allow teachers to spend more time delving deeper into key topics and focus less on simply rushing through a long list of factual details in an attempt to cover all of the required topics.”

British Columbia Ministry of Education

For example, a Ministry overview for the Grade 9 social studies curriculum notes that students are expected to study: “political, social, economic, and technological revolutions”. Suggested topics include the American and French Revolutions, which I learned as a part of the old curriculum, but also the Haitian Revolution. The Canadian Red River Resistance is a suggested topic too. Other revolutions in world history would be welcome too, even if they are not on the suggested topics list. A current debate in history education concerns the decision to teach history about national histories versus teaching history content which will empower students to become better global citizens.. In this case, BC’s curriculum is clearly open to making room for other subjects and stories at the discretion of the teachers.

In the previous curriculum, the curriculum that I went through, Canadian history formed a large part of the content I learned. In elementary school I learned the basic history of early Canada. In high school through Grades 9-11 I was taught the history of Canada up to the turn of the 21st century. Now that Canadian content that was normally taught over the span of three years has been compressed into Grades 9 and 10, which has opened up more room to teach world topics. In general, content that was prescribed in the previous curriculum has shifted down one grade. This is illustrated in a detailed chart created by Glen Thielman. The shifting of the content was one of the main criticisms of the new curriculum that came from teachers. Tried and tested lesson plans had to be reworked and those who did want to highlight Canadian content found their time available crunched. Thielman writes on his blog “Many teachers have expressed concern over the loss of Social Studies 11 [the previous curriculum taught in Grade 11 to students aged 16-17], considered a “flagship” course due to its emphasis on the world wars, a changing Canada in the 20th Century, and meaningful exploration of politics, government, climate change, and global population and development issues.” Gibson confirmed that among teachers the content shift “was controversial for sure.”

However Gibson believes the change “opens things up more” and provides more choice to students and teachers. There is no longer a mandatory Social Studies 11 course, so students have more space in their timetables to choose specialised courses in their final two years of high school. There are seventeen course options under the banner of “social studies” including courses like Social Justice and Indigenous Studies. The full list of possibilities can be seen on the Ministry website, though it is important to note that what courses are on offer varies per school and is based on the demand from students and the teachers available to teach these courses.

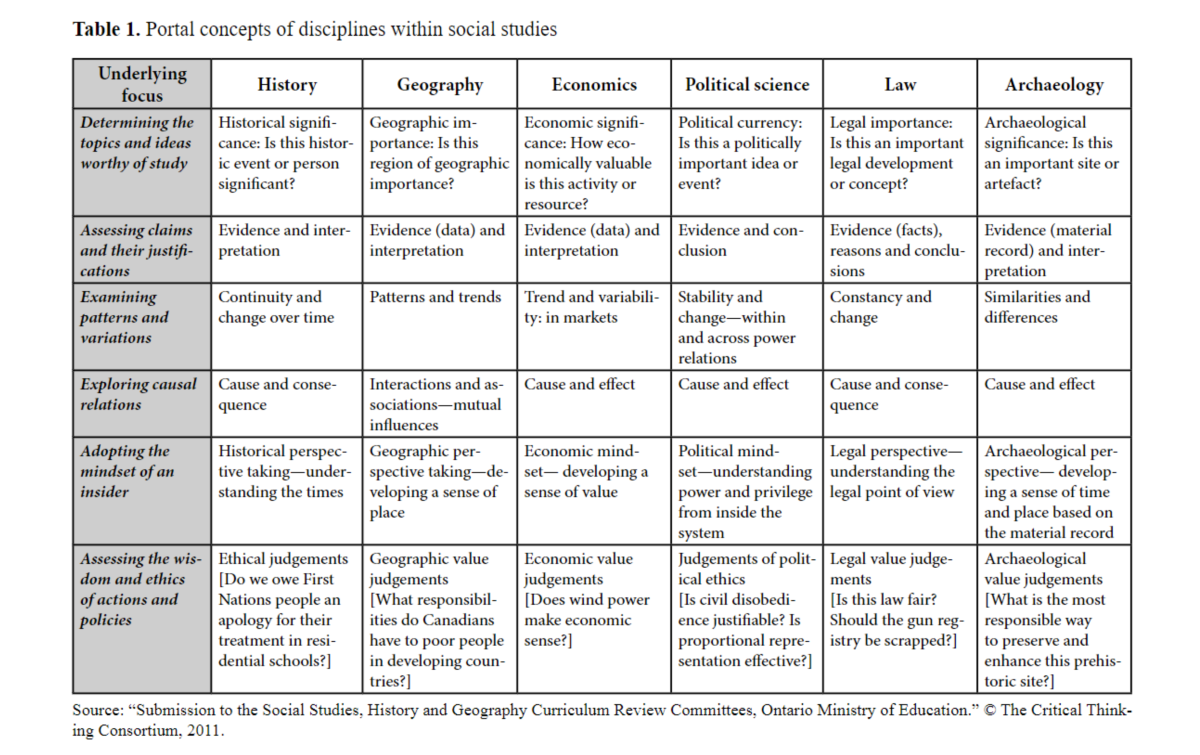

As noted, what underpins the new BC curriculum in general are the “Core Competencies”, as well as content. Beyond the Core Competencies of the entire curriculum, the social studies curriculum in particular looks to place “greater emphasis on acquiring and developing key disciplinary thinking skills.”[4] These six “disciplinary thinking skills” are: 1) significance, 2) evidence, 3) continuity and change, 4) cause and consequence, 5) perspective, and 6) ethical judgement. These six skills are heavily influenced by the work and findings of The Historical Thinking Project, a project funded by the Department of Canadian Heritage and The History Education Network.[5] The BC Ministry’s six “disciplinary thinking skills” are taken almost verbatim from the six historical thinking concepts identified by the project: 1) Establish historical significance, 2) Use primary source evidence, 3) Identify continuity and change, 4) Analyze cause and consequence, 5) Take historical perspectives, and 6) Understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.[6] More can be read on these concepts in The Big Six, a book by Canadian academics Peter Seixas and Tom Morton which resulted from the project.[7]

The goals of the historical thinking concepts are to support students to be historically literate and to think critically about what information they learn instead of simply parroting it back. This brings in some elements of how history is created as an academic discipline. As Seixas and Morton write, “Sometimes historians explain the rules of the game and show us the process they follow to construct history, but more commonly we read in their histories only the end product-their historical narratives. In some sense, they are like the directors of a play. Too often, our students see only the play. We want them to peer backstage, to understand how the ropes and pulleys work that make the play possible.”[8] Of how these concepts play in the BC curriculum, Gibson says it is taking “a different stance towards information” and while content choice is still significant for the curriculum, the point is not “read this textbook, answer the questions at the very back […] and you have a test next week on all the information. That’s not what we’re trying to get at.”

“Sometimes historians explain the rules of the game and show us the process they follow to construct history, but more commonly we read in their histories only the end product-their historical narratives. In some sense, they are like the directors of a play. Too often, our students see only the play. We want them to peer backstage, to understand how the ropes and pulleys work that make the play possible.”

Peter Seixas and Tom Morton, The Big Six (2012)

As noted, some criticism emerged towards historical thinking concepts influencing the new social studies curriculum as a whole. Proponents argue that the concepts can be effectively adapted for the other sub-disciplines of social studies, as illustrated in a chart developed by Roland Case of The Critical Thinking Consortium.

[9]

[9]

In retrospect Gibson suggests that some may think they could have considered other approaches to history and social studies education in the beginning stages of the curriculum development. However the work of the Historical Thinking Project was in the right place at the right time. Firstly, the “Big Six” aligned well with the “Core Competencies” of the revised curriculum. The Historical Thinking Project was already gaining momentum within Canada, in other provinces too. Finally, Peter Seixas was based at the University of British Columbia, which also raised the profile within the province. These factors all worked together to make the six historical thinking concepts the driver of the new social studies curriculum. As Gibson describes, it seemed like a “natural fit”.

Focusing on Indigenous history

So far in our look at the new BC social studies curriculum, we have seen two main areas of discussion in current history education have played out in BC. Firstly, questions around content choice, in particular between national and global focus, and secondly, the balance between the content and skills driving the curricula. I can add a third current and important discussion to this list: incorporating Indigenous history, ways of knowing and epistemology. This topic was the original impetus for looking at BC’s curriculum in the first place. Canada was a country born from colonisation. Traditionally, how history was taught in Anglophone Canada could be called “Great White Man History”, a simple national narrative which privileges the experiences of mainly Anglo- and White-Canadians.[10] This excludes the Indigenous peoples in Canada from being actors in how history is taught in Canada. Similarly, settlers from non-European backgrounds were also often ignored in traditional narratives. There are regrettably ample examples in Canada’s history of racism and discrimination which were not always brought to light in classrooms, though change has already been seen in the last decades. From personal experience, I did learn about aspects of this in high school: residential schools where at least 150,000 Indigenous children were forcibly sent and encountered physical, sexual and emotional abuse; the Chinese head-tax and exclusion act, in which Chinese immigrants were taxed to dissuade immigration and then finally banned entirely; and the ship called the Komagata Maru on which hundreds of mainly Sikh men were barred from entering BC despite being subjects of the British Empire and so were entitled rights to entry. From elementary school I also received an introduction to the local Indigenous culture. My elementary school was near the Musqueam reservation and Musqueam members were a part of our student body and staff. I remember some elements of Musqueam culture at school, for example during story time or art classes my class was invited one year to join celebrations for National Aboriginal Day (now called National Indigenous People’s Day) at the Musqueam reservation . However, my anecdotal experience is certainly not shared by all Canadian students. This was highlighted by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) report. This commission was established in 2008 by the Canadian government with the purpose of documenting the history and lasting impacts of the Canadian Indian residential school system on Indigenous students and their families. Their final report published in 2015 identified education as “the key to reconciliation” and called for changes in order to “remedy the gaps in historical knowledge that perpetuate ignorance and racism.”[11] Reforms on history education remain an important debate in Canada to remedy discrimination faced by many in Canada, both historically and in the present day.

One facet of addressing these injustices for the Indigenous people of Canada is integration of their knowledges and epistemologies into the curriculum. The BC Ministry aims with the new curriculum for all subjects to integrate “Indigenous perspectives into the entire learning journey, rather than into specific courses or grade levels” with the aim “to ensure that all learners have opportunities to understand and respect their own cultural heritage as well as that of others.”[12] This goes beyond simply additions of content, but integrating a respect and understanding of ways of knowing and epistemologies. The BC Ministry’s curriculum referenced the “First People’s Principles of Learning” as developed by FNESC (First Nations Education Steering Committee).[13][14] For the social studies curriculum in particular, FNESC also developed teaching materials for the new curriculum related to residential schools.[15] Designing the right resources for this can be challenging. Gibson notes of the FNESC resources which he also helped to develop, “we wanted to make sure that we highlighted the agency of first nations communities and resistance” which tells a “more complicated story”. Content in the past may have noted Indigenous peoples but looked more at what was done to them. The new content here looks to bring in Indigenous perspectives and testimony thereby giving them agency in history. As I examined in my blog post on decolonising history, reform in the methods by which history is taught is just as important as simply adding to the content, and the BC Ministry’s published approach to the new curriculum appears to acknowledge this.

The integration of the historical thinking concepts in the social studies curriculum are also a means to challenge previously accepted histories, and examine their power and hegemony in society. Take for example, the criticism in Canada of statues erected to Canada’s first Prime Minister John A. Macdonald. Public critique has been building to take down statues to the man who while in office introduced the residential school system in Canada among other discriminatory policies. Defenders of the statues often argue Macdonald was a man of his time, and to remove the statues would be to erase a part of Canada’s history. As Gibson tells me when he boils down the arguments at play over statues and commemorations, he sees it as a debate between “people who understand history as the stories we in the present tell about the past, versus people who think it’s the true story.” By understanding history, through the historical thinking concepts, it is apparent that a commemoration such as the statue of John A. Macdonald is “an interpretation of the past, it was created by people who had power in a certain situation” and if a statue is torn down, spray painted or otherwise altered, “it’s a reinterpretation of history, as we do all the time.”[16] The goals of the historical thinking concepts are to give students tools for history not just in the classroom, but beyond it. As Gibson says, though some content is important, “I know that they’re going to continue to work with history throughout their whole lives” and so he wants to give students the tools to “work with it, understand it, comprehend it, and talk with other people about it.”

Assessment Time

The new BC social studies curriculum was rolled out over six years ago. The question follows: how has the change gone? In regards to the integration of Indigenous content and ways of knowing, criticism has emerged that the historical concepts at the core of the social studies curriculum are born of Eurocentric epistemology and thus incompatible with Indigenous ways of knowing and reconciliation in Canada. To gain an insight into this debate, I suggest the 2018 article by Samantha Cutrara [17] which is critical of historical thinking and a 2019 response to this by Gibson and Case.[18] Furthermore, though Indigenous ways of knowing and content are meant to be integrated throughout the curriculum, this is difficult to do in practice. It requires support and training for teachers in epistemology, and as Gibson tells me, defining even “so-called Western ways of knowing” would be difficult in the first place for many teachers. Moreover, the freedom of choice in the new curriculum to choose content means that while space exists to explore Indigenous content, it is not mandated. Therefore teachers could choose content that they have traditionally taught before and are more comfortable with.

Nonetheless, Indigenous history is arguably becoming more prominent in BC classrooms and throughout Canada more generally. As the Ministry states on their website, “The redesigned curriculum builds on what has been learned” in integrating Indigenous content into the classroom.[19] Gibson says “my suspicion would be that people are teaching a lot more Indigenous history than they were ten years ago”. He bases this on a recent survey asking Canadian history educators from kindergarten to post-secondary level what they thought were significant events in Canada’s history.[20] However he adds that not enough research was done prior to afford a clear benchmark for comparison. The change in the BC curriculum to highlight its Indigenous history could be viewed as a confirmation of trends that were already underway in Canadian society, rather than a radical shift to something new.

Within Canada, the new curriculum has gained attention recently as the Northwest Territories (NWT) announced in December 2021 that it would be adapting BC’s curriculum for its own territory’s education curriculum.[21] Previously this territory had adapted their curriculum from Alberta, the province to their south. After a two-year review of other Western provinces’ curricula, BC’s curriculum was chosen, its integration of Indigenous knowledge and student-centric model playing a large part in the decision. Half of NWT’s students are Indigenous and Education Minister R.J. Simpson noted “We need to ensure that we are teaching to Indigenous students in a way that they are going to relate to and is going to be valuable to them.”[22] As noted, the BC curriculum looks to incorporate these elements across all the school subjects. However, in the CBC article reporting on this announcement, it is added that this could be seen as a particular rejection of Alberta’s social studies curriculum, whose recent revisions were critiqued for Eurocentrism and a lack of Indigenous perspectives. No doubt those behind BC’s new curriculum will be pleased with NWT’s adoption. And those in Europe may too want to learn from BC and examples in the rest of Canada. Yet it is important to add that these developments in Canada are recent, and questions on how best to serve Canada’s Indigenous peoples in education vary across the large country and are by no means resolved.

Looking at the rollout of historical concepts by teachers and students in the curriculum more generally, the results are mixed and again difficult to assess. Gibson is critical of the provincial government which passed the responsibility for inservicing teachers to local districts and school boards, with limited support and resources. Textbook companies filled the gap for resources by creating resources of varying qualities. Lindsay explains to me that the textbooks I grew up using were essentially repackaged for the new curriculum, adding a few notes on historical thinking concepts but largely offering the same narrative text as before. There is a TeachBC website [23], where teachers can upload their materials and lesson plans. Gibson, however, thinks the uptake on this website’s resources may be low. Teachers are sometimes hesitant to share materials, often out of concern of being criticised by their peers. It appears the freedom inherent in the curriculum could give teachers little incentive to radically change their teaching. On the other hand, opportunities exist to try new things. Gibson tells me about resources which he helped develop with the Nelson textbook company, foregoing traditional textbooks for activity cards sets that work with pictures and evidence.[24]

A main problem appears to be lack of research on the rollout of the curriculum. Gibson finds that the best assessment he currently has is asking his teaching students about how things went when they return from their practicum in schools. Gibson is part of a research team Thinking Historically for Canada’s Future, which is launching a Canada-wide survey which may help to answer some of these questions in BC. This extensive research survey will invite teachers and students to participate, to assess their engagement with history. The three main aspects being considered are Civic Engagement, Historical Thinking, and Indigenous Ways of Knowing.[25] It doesn’t sound like a quick multiple choice study either; the survey took 1.5 years to develop and takes about half an hour to complete. Preliminary results are already coming in from the first teachers interviewed. Gibson, who is part of the grant organisation, notes “It’s not going to be definitive but we’re hoping at least to get some kind of insight into this that we haven’t had forever”.

The new social studies curriculum in BC clearly reflects debates that those involved in history education will be familiar with. What content is included, how it is taught, and concern for decolonizing the curriculum, taking into account Indigenous history as well as other minorities in Canada, are all questions that come into play. In each of these three aspects, the new social studies curriculum in BC has made some significant changes. However, it has been over six years since the roll-out and seeing how these aspects play out in practice are difficult to decipher, even for professionals involved. The case of the BC social studies curriculum shows that the work cannot stop once the curriculum is published. Support in the way of communication, training, and practical resources are integral to the goals of a new curriculum being achieved. Furthermore, some level of assessment is required to monitor for progress. I hope that this exploration has been an interesting case study, in order to see how new ideas in education can actually come to fruition within a curriculum, and also given a hint at the possibilities that exist with these new concepts if they are fully grasped.

_________________________________________________

Footnotes

[1] https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/introduction.

[2] https://www.thielmann.ca/new-social-studies-curriculum.html.

[4] https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/introduction.

[5] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/historical-thinking-concepts.

[6] https://historicalthinking.ca/historical-thinking-concepts.

[7] The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, Peter Seixas, Tom Morton. Nelson Education, Toronto, ON (2013).

[8] Seixas and Morton, The Big Six (2012), p 2-3.

[9] Gibson, L. and Case, R., “Historical Hegemony or Warranted Adaptation? A Response to Smith”, Canadian Journal of Education Vol. 40 No. 2 (2017), p. 7.

[10] Canada has two official languages: English and French. Debate also exists on the place of Franco-Canadians in mainstream Canadian history and the lack of dialogue between the two in academia and society in general.

[11] Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 234.

[12] https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/overview#indigenous.

[13] http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/.

[14] I also reached out to FNESC to interview them for this article but unfortunately they were unavailable for interview due to limitations in staffing capacity, which means they need to focus on their core initiatives.

[15] http://www.fnesc.ca/irsr/.

[16] More work by Gibson on this topic can be read in “The Case for Commemoration Controversies in Canadian History Education” Canadian Journal of Education Vol. 44 No. 2 (2021).

[17] Cutrara, S.A., “The Settler Grammar of Canadian History Curriculum: Why Historical Thinking Is Unable to Respond to the TRC’s Calls to Action” Canadian Journal of Education Vol. 41 No. 1 (2018).

[18] Gibson, L. and Case, R., “Reshaping Canadian History Education in Support of Reconciliation” Canadian Journal of Education Vol. 41 No. 1 (2019).

[19] https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/overview#indigenous.

[21] There are three territories in Canada, which occupy the northern region of the country with 60% of Canada’s land but only 3% of its population. Territories such as the Northwest Territories have less devolved powers mainly due to economic, social and demographic realities linked to their northern location. https://www.canada.ca/en/intergovernmental-affairs/services/provinces-territories.html.

[23] https://www.bctf.ca/classroom-resources.