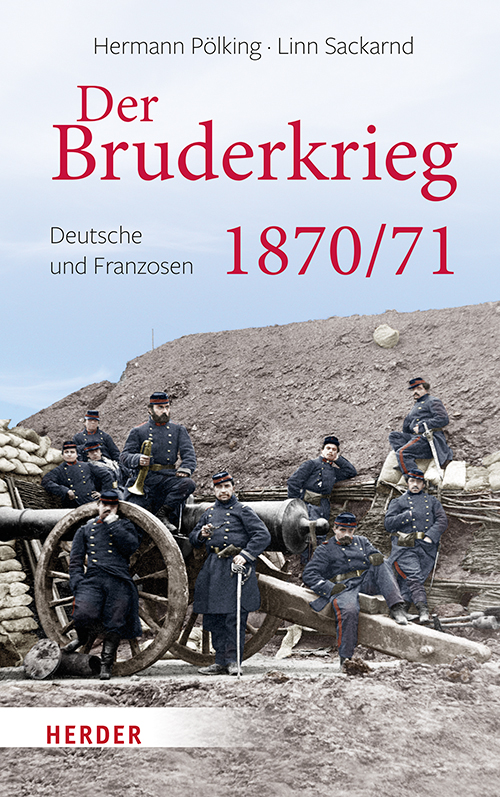

This year it is 150 year ago that the German Empire was founded on 18 January 1871 during an improvised and sober proclamation ceremony in Versailles. The authors Hermann Pölking and Linn Sackarnd describe in their book Der Bruderkrieg 1870/71, Deutsche und Franzosen, how reluctant the Prussian King William I was to receive this imperial crown, and that he only, after much discussion, agreed on ‘Emperor of the German Realm’ as title instead of on ‘German Emperor’. They also demonstrate that, despite the military victory of the troops representing the different German States, creating a united German Empire was not a step applauded by all other monarchs, with Ludwig II of Bavaria particularly reluctant. Only after considerable concessions, which are still the basis of the present-day Bavarian exceptionalism, did the King agree that Bavaria would become part of the Empire. Only ten days later an armistice was agreed in the war between Germany and France.

This war began in the summer of 1870, when both Prussia and France had interests in fighting a war against each other and believed that an easy victory would be at hand. The authors demonstrate, contrary to the common myth, that it was certainly not only Bismarck who orchestrated the beginning of the war. Many within the political and military leadership and public opinion leaders from both countries welcomed an aggressive and violent competition. What followed was a savage war, which led to the death of approximately 200.000 soldiers and left many more wounded and deformed.

This sizable and rich publication goes deep into the political developments during the war. The French Emperor Napoleon III surrendered quite early in the war and became a – well nurtured – prisoner of war, and left France without a legal counterpart for the Germans. The new French Government of National Defence, based in Tours, was not considered as representative for the whole country by the Germans. This fact contributed considerably to the continuation of the war, as did the German demands for Alsace and parts of Lorraine as war booties.

The many bigger and smaller battles and the sieges of Metz and Strasbourg are described in too much detail for my taste. Unfortunately, such detailed descriptions also rarely go with situation maps, which could certainly have enlightened this poor reader. But what makes the book really interesting – and useful for school education – are the many ego documents (or personal life story sources) of soldiers and civilians giving insights in the state of warfare in 1870 and their social consequences. While the German High Command found, as high noblemen, suitable headquarters in Versailles, their troops continued fighting and struggled with a lack of appropriate shelter, clean clothing and food. Many quotations from letters make the reader aware of how difficult the situation was for ordinary French and German soldiers and often even for their officers. The French civic population fell victim to the military violence but even more through the food and goods requisitions by both the occupying and defending armies. Despite the suffering of the ordinary people, the French population continued to stand behind their leaders and supported their decision to keep fighting.

A special feature of this war was the fact that the combatants made prisoners of war, basically for the first time. This happened at both sides but most prisoners of war were made among the French troops. Almost 400.000 of them were interned in Germany, often under very difficult circumstances. In the end of the war soldiers fled across the French borders and almost 100.000 were interned in Switzerland and more than 5000 ended up in Belgium. The International Committee of the Red Cross created a special tracing agency for these prisoners of war.

This publication offers a genuine cross-border narrative, despite the fact that both authors are German. It uncovers the story of a war, mostly mentioned as a minor conflict, which was in fact the prologue and final rehearsal for the First World War. For those who read German, a really good read!

Hermann Pölking-Eiken and Linn Sackarnd, Der Bruderkrieg, Deutsche und Franzosen 1870/71 (2020) (686 pages). Available also as a film documentary in three parts by ARTE.

Hardcopy 38,00 €; eBook (PDF) 29,99 € eBook (EPUB) 29,99 €

Joke van der Leeuw-Roord founded EuroClio in 1992, and since then she has acquired recognition as an international expert on innovative and trans-national history, heritage and citizenship education. Currently, Joke van der Leeuw-Roord is special advisor for EuroClio.