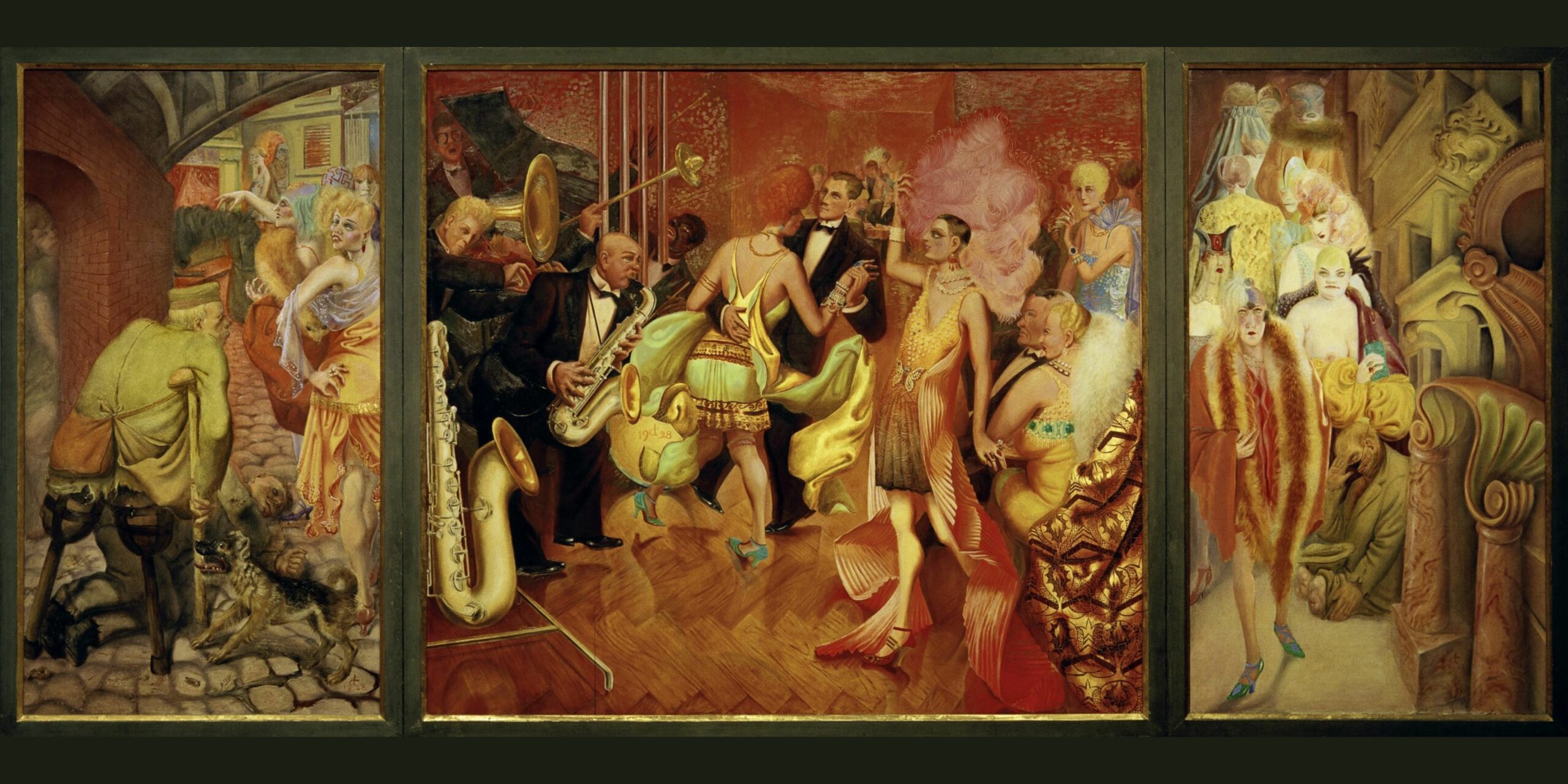

Image: Gross Stadt (Metropolis), by Otto Dix, 1928, Germany. akg-images via Facing History and Ourselves.

Guest blog post from Facing History and Ourselves

In 1916, in the midst of a world war, the American philosopher and educator John Dewey wrote "democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife."

Here we are, more than one hundred years later, with an opportunity to take Dewey's words to heart and imagine what they might mean for us as citizens and as educators. Over the last several years, we've been reminded–by journalists, scholars, thought leaders, and young people in our streets–that democracy in countries around the world, including the one from which I write, is fragile. So-called "consolidated" democracies have experienced democratic decline and countries once believed to be democratic are now considered examples of competitive authoritarianism.

Like Dewey, we are living in a period of great change and transformation. We might even think about it as a time of transition. In that spirit, we might consider other periods of transition–such as the period in the US following the Civil War, Reconstruction, the period between the world wars in Europe, including the period of the Weimar Republic in Germany, and the later years of apartheid in South Africa and the early years of democracy– as windows and mirrors, opportunities for reflection, for hearing echoes and for making connections to our own time and place. These periods provide us with the ability to step back and ask ourselves what undermines democracy, what strengthens it and what do we need in terms of knowledge, skills, behaviors and dispositions to create healthy democracies? And what role does education play in that work?

As educators of civics and of history, we are uniquely positioned to engage in this learning and in conversations with our students and colleagues about these issues. Schools and classrooms–even virtual classrooms–provide us with a golden opportunity if we choose to take it: we can stop and think. We also know that so much more happens in classrooms and schools than teaching and learning about particular subjects. These are spaces where we develop relationships, where we engage with people outside our families and most intimate friendships. Democracy is about relationships. Trust is the glue that binds them, and classrooms and schools provide a unique opportunity to build trusting relationships across generations and differences.

Moreover, classrooms and schools can provide a context where we engage with ideas that have the potential to inspire us to ask questions and to confront our own beliefs, biases and prejudices. And, history classrooms have the potential to provide a rare opportunity –to develop what author Isabel Wilkerson refers to as radical empathy. She writes, "Radical empathy… means putting in the work to educate oneself and to listen with a humble heart to understand another's experience from their perspective, not as we imagine we would feel. Radical empathy is not about you and what you think you would do in a situation you have never been in and perhaps never will. It is the kindred connection from a place of deep knowing that opens your spirit to the pain of another as they perceive it."

Many educators in the global North are beginning a new school year. It's an exhausting and exciting time to re-enter the classroom. As you begin teaching this year (or as you continue your classes for those of you who are in the midst of a school year), consider the possibility of using democracy as a guide. How might thinking about democracy inform the way you set up your classroom? The establishment of a class contract? What you teach and how you teach? How might democracy provide a lens for exploring historical moments and events? What might it illuminate or obscure? What might it shed light on as we grapple with fundamental questions about how we are going to make democracy work in countries around the world? How might your definition of democracy change over the course of the year and in light of the different histories you teach? How might your students' feelings and thoughts about democracy change your own or inspire you to question your own? How will you share this learning with others?

We hope this blog post has inspired some reflection as we start the new school year. For more on history education and democracy, join our EuroClio webinar series from 15 September to 27 October.

About the author

Karen Murphy, Director of International Strategy for Facing History and Ourselves, is based in New York City and grateful for the opportunity to work with educators and representatives from civil society organizations across the globe. In addition to the programmatic work of Facing History and Ourselves, Karen is immersed in a longitudinal study of adolescents from divided societies with identity-based conflicts (South Africa, Northern Ireland, and the United States), and the ways these young people develop as civic actors, including the factors that impede and support their development. Karen's doctoral work focused on the role of race and racial violence in the construction of United States national identity.

Resources provided by the author for inspiration and opportunities for reflection:

Examine the complicated history and lasting legacy of apartheid in South Africa.

The Weimar Republic: The Fragility of Democracy

The Reconstruction Era and the Fragility of Democracy