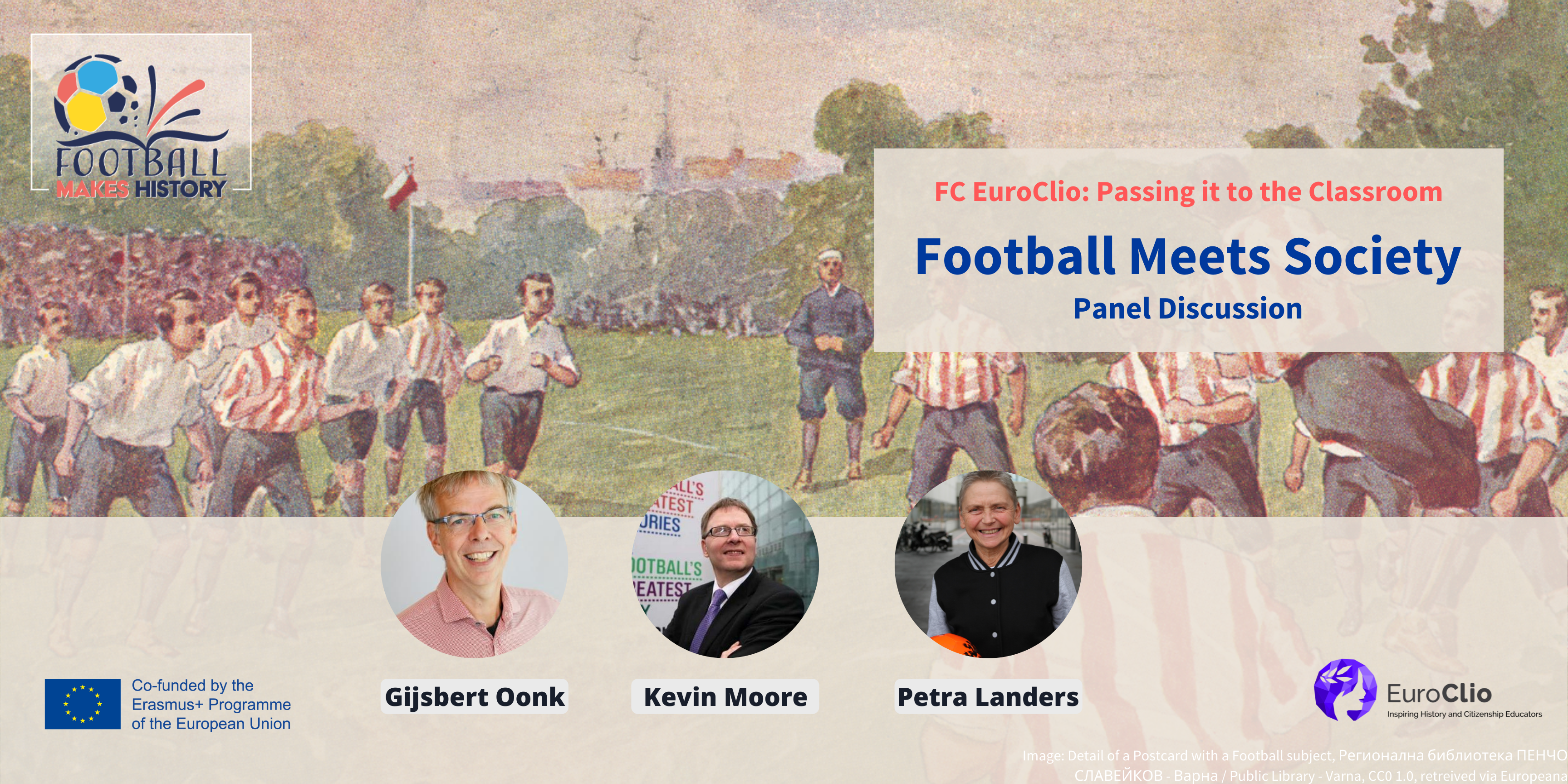

On May 28th, Gijsbert Oonk, Kevin Moore & Petra Landers kicked off 'FC EuroClio', a webinar series through which we tackled football and social issues to explore how football history and society intertwine. The panel discussion revolved around personal experiences of football pioneers and considerations about football as cultural heritage.

Football Makes History

The only girl in the field

Coach, mentor, former football player, and contributor to the rise of women's football. Petra Landers became a member of the first-ever German women's national football team in 1982.[1]

Petra is an international footballer who also won the European championship, but looking at her, you see a down to earth, yet incredibly determined woman who still has the same passion for football as when she started off as a kid. Petra got an interest in the game in a time when football was a sport only for boys and girls were set to do other kinds of activities. However, she does not shy away from saying "I think football was already inside of me when I was born." When at the age of 8 she was invited by her cousin to play on the streets, Petra started regularly playing with the boys from the neighbourhood. She was always ready to play, always wearing her football shirt underneath her clothes. Despite being the only girl in the group, she felt welcome and did not have any sort of unpleasant experience. It was only when she joined the women's team that she started hearing rude comments. "It was very new for me, but it didn't matter because I truly loved the game." Women's football was forbidden in Germany (as well as in other countries) until 1970 and Petra clearly remembers that time:

"On football pitches you could see only men: women were at home cooking"

Luckily, the fear of discrimination and societal constraints never prevented Petra from trying to enter the footballing world. It was a friend of hers who encouraged her to play for Bergisch Gladbach: when the coach saw her playing, he was amazed by her talent and decided to take her in the team. Nevertheless, it was not an easy game: her boss tried to stop her from representing Germany for the European championship in 1989, but she made clear that she was ready to quit her job to be free to go her own way. In the end, her determination made him change his mind and he eventually supported her decision!

In Support of Women's Football – from Europe to Africa

After contributing to the rise of women's football first in Germany and then in Europe, Petra decided to turn to Africa, where she is now training young girls. When she travelled there for the first time in 2014, Africa was obviously new to her, but seeing children playing football in the villages reminded her of her childhood and a strong empathetic feeling grew inside of her. "It was a feeling I got, I can't describe it, it was amazing". Watching those kids playing, she could see herself growing up and working hard to become a professional player. Petra is a source of inspiration for those kids: she does not only embody an example to follow, but she also gives them the hope to think that one day, they can become footballers or coaches too.

"You can't imagine what areas I visited. We are now trying to get those children who can't go to school. There are so many girls that are working at home, they have to do the household, they have to work, they don't have the money to go to school. They don't really have a childhood. We want to give them this chance."

In 2017, Petra Landers was part of an important awareness programme in which a world record was challenged – the women's team that played on the highest level on the Kilimanjaro. When asked whether she was willing to join, Petra immediately answered yes. She started to train nearly every day, again after many years. They had to climb and walk a lot, and not always in great conditions "The last night we went up to the mountain, it was -20 degrees, it was so cold. After one hour and a half, our drinks were already frozen, and it was dark and we were walking as fast as snails. The oxygen was getting thinner and thinner. It was hard to breathe, but if you have a goal, you try to give everything until you can."

"We wanted to empower all the women and girls all over the world. We wanted to give a sign: if you set a goal, you can get everything, you can do everything. It's true."

Africa opened up Petra's eyes to a completely different reality, and after changing the faith of women's football, she wants to change the life of those African kids. Her next goal is to have her own football school in Ghana. "I want to move to Ghana, but not for talent, I'm not looking for talent. I want to give the children living outside the village a chance. They don't have the chance to join projects because it's too far away. They don't have shoes to walk or run for so long. They are playing barefooted but they are playing with bright eyes. There are so many children who don't have this chance and I want to give them one."

Petra's words opened the doors to a different kind of conversation we should have in current society, where the European situation is rather different: football is often a matter of cups and medals, and football museums end up being places of celebrations rather than an objective look at football history and source of reflection.

Football museums: celebrating heroes or reconnecting with the past?

Kevin Moore, world-respected football historian and founding director of the English National Football Museum, shared with us the reasons why he wanted a National Football Museum for England in the first place. Deeply convinced of the historical significance of football – "there are more nations in FIFA than in the United Nations!", he observes – he explains:

"The reason why I applied for the job was because I did not want it to be Disneyland football. I wanted it to be an objective look at the history of the game, to treat the subject seriously and with objectivity, not a celebration of football – but an honest look at the game, every aspect, including the negatives such as sexism, racism and homophobia in the game."

Kevin has gladly remarked that whilst setting up the museum, he could freely bring the true history of football into the museum. In club museums the importance of big cups and the heroes they have is indeed too often overvalued. There might be small display elements about WWII, stories about racism, homophobia or other issues, but those are often confined to a corner and those issues always play a minor role. Due to the limited space within the permanent galleries, these issues are more likely to be tackled in temporary exhibitions. For example, the English National Football Museum had in 2003 an exhibition on Arthur Wharton, the world's first black professional footballer – telling the story of how he came from Ghana to England in 1882 to learn to be a methodist missionary but instead decided to be a footballer and athlete. In 2005, they had the world's first exhibition on women's football during the UEFA European Championships in England. As these exhibitions are temporary, they were able to tackle issues like gender or racism more in-depth, and on their website or through learning programmes.

How do we go from creating a hall of fame of heroes to creating a hall of history that engages meaningfully with the history and the local context?

Kevin speaks up about the dangers of club museums being too celebratory, as they see the museum just as a display through which showcasing their victories and their heroes, leaving out other (hi)stories. "Football is about stardom, which is why an inclusive hall of fame, to some extent, is a good idea. We all have our heroes." However, visiting a museum is and should be an informal learning experience, a way through which people inadvertently learn. The English National Football Museum launched a special session for people with dementia back in 2017, around the 50th anniversary of England winning the World Cup in 1966: their memories were prompted by football and it was a great way for people to connect. In 2018, a similar project was carried out in The Netherlands by the professional football club Willhelm II Tilburg: "Football Memories" brought together people with similar backgrounds to show them old parts of football matches. In both cases, football memories seemed to create an environment where the elderly were able to not only recall memories, but also make new connections that they normally would not be able to make.

Local public museums have an important role, but as not every football club has or can afford to have a museum, it is important to inspire football clubs to engage more socially, for example by running some social reminiscence programs with their fans. Whilst most clubs interested in social responsibility do all kinds of programmes related to physical exercises, healthy diets, etc., they are rarely focussing on making educational programmes on history. To engage socially, clubs should relate more strongly to their fans – as Kevin observes, "the fans carry the history of the club, they are the ones who hold the tradition, the sense of belonging and the identity, and the club doesn't. The club is whoever owns it now, and is a private entity." It's a money issue, but also a matter of ownership.

"Football Makes History has a great role in showing the value of history, learning, engagement with schools, connecting schools and older people and football clubs together and using the social power that football clubs have."

A European Football Museum?

Would the idea of setting up a European Football Museum be feasible? Although a world football museum already exists, various and controversial opinions were given on this topic. One of the issues is that the passion that each set of fans has is for either their own club or football in the nation – which is why national football museums are growing in numbers, so these kinds of museums would not work by continent. "Certainly you won't have a museum that tells the story of European football, because that's with the individual museums. What you could have is a very interesting museum about the European football competitions and also how football spread around Europe and what that common culture of football across Europe means." In other words, having a museum that tells the stories of the champions league, the European cup, the development of football in Europe. As European football does not exist and has never existed in isolation, it's rather a story of migration and connection, it would be interesting to trace the history of football in Europe on maps – and investigate further to what extent football and migration are connected.

"Football is too important just to be in football museums: football and sport should be in every single history museum, local and national. Yes, we should have football museums, too. But football is part of history and therefore football makes history, history makes football."

Do you think that Football Makes History? Sign our Petition!

Our football team has developed Policy and Action Recommendations aimed at ministries of education, sports, heritage – and the footballing world. You can now find the Manifesto on the Football Makes History website.

Do you think that football can open doors to conversations we need to have, but also inspire us to take action? Then support us in giving football history and football heritage the attention it deserves!

Written by Giulia Verdini

[1] Petra was in fact also part of the team from Bergisch Gladbach representing Germany in the 1981 unofficial World Cup in Taiwan

Football Makes History in Numbers!

- 6 partners from 4 countries

- 30 developers, from 15 countries

- 100+ life stories published on the website

- 18 lesson plans published in English on Historiana

- 12 lesson plans and source collections to be published soon!

- a toolkit with 30 non-formal activities will be also published soon! >> Do not miss them!