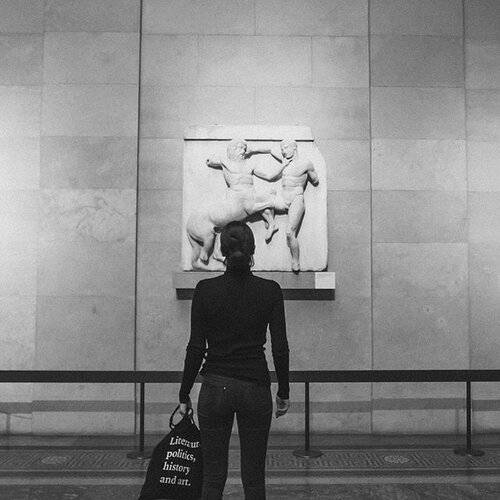

When Issabella Orlando joined the Contested Histories team for a week-long research assignment in December 2020, she already had an extensive project on contested heritage under her belt. While studying full-time at Oxford University, Issabella wrote and directed the short documentary ‘The Return Address: Where Does Heritage Belong?’. The film delves into the question of how to approach contested heritage items in museums. Supported by expert interviews and footage from the world’s most extensive galleries, The Return Address highlights the same complexities inherent to the Contested Histories project: when confronted with new historical evidence and previously underrepresented narratives, how do we construct our sites of memory to reflect these nuances? After the completion of her internship, we checked in with Issabella to talk about her work on Contested Histories, the process of making a documentary, and her hopes for the future of the cultural heritage debate.

Thank you so much for meeting with us Issabella! Before we delve into The Return Address, could you tell us a bit more about yourself and why you chose to work with us at the Contested Histories project?

My pleasure! I was born in Canada to an Italian family. When I was 17, I moved to London to study Classical Studies at King’s College London, which also presented me with the opportunity to study in Greece during the summer. Currently, I’m pursuing a master’s in archeology at Oxford. Aside from my educational background, I have always been a writer. My work focuses on travel, cultural heritage, and sustainable development. It’s the intersections between human society and the material world that keep me inspired.

Long before joining the Contested Histories project, I was fascinated by museums and their curated narratives. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement’s intensification in 2020, it seems that the collective psyche is also paying closer attention to the representation of history in contemporary space. For the project, I ended up fact-checking several case studies and writing a piece on how modern nations stake their claims on ancient narratives – for example,

how Macedonian nationalists are keen to claim the legacy of Alexander the Great. I also curated a list of examples of contestations in museums and galleries, should the project’s scope expand to include them in the future. Such settings are subject to similar outcries for truthful representation of the past and restitution for historical and ongoing injustices.

Why do you think projects like Contested Histories and your documentary The Return Address are necessary in today’s society?

What I hope to underscore in all of my work is that the past is a powerful tool – narratives can be used in different ways, both positive and negative. Heritage can build up communities and heal past traumas; conversely, it can propagate hateful views and be weaponised against certain groups. Projects like ours show that history is not a dead discipline. The past is not that far away and history still affects our current points of view. It connects us to where we come from. Through these projects, we must also look at the ugly parts of the past and attempt to deal with them.

While researching contested cultural heritage debates, did you find any solutions for people attempting to deal with the past?

As I show in the documentary, it is a very case-by-case situation. Each case is so nuanced; there is no one size fits all solution. In general, however, I believe that addressing contested history cases cannot involve a strictly top-down approach. It is crucial to involve as many community members as possible and to contact historical groups tied to the history in question to strive for inclusive decision-making. We should also consider whether a heritage object is part of a living culture or an ancient one, where the object is claimed by a nation regarding itself as its successor. When a heritage object is important to a living culture and its people, I would say claims for repatriation are the most justified.

Keeping those ideas in mind, was there a case that handled contested heritage issues in a positive, constructive way that stood out to you?

One that comes to mind is the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, where curators have inherited quite a dark history but recently have done a good job contacting relevant communities about artifacts in their collection. We should keep in mind that there are solutions other than simply sending something back. In some cases, cultural groups whose heritage is on display have allowed museums to keep objects despite the questionable ways they acquired them. Some exhibitions can tour before reaching their final resting places. New technologies allow for replica making, which we can use to showcase versions of materials that no longer reside at the museum. Again, each case merits its own approach.

Going back to the process of making The Return Address, what inspired you to take on such a project?

I became aware of the debate around repatriation during my undergraduate studies, specifically while studying at the British School of Athens, Greece. When I looked to the media, I found that many reports focused on a few high-profile cases. However, when I discussed the issues with my friends and fellow students while visiting museums back in the U.K., I found that they were not as familiar with the wider repatriation debate. This inspired me to create a piece of media that would lay out the background of the discussion, as not everyone has access to academic materials. I wanted it to be engaging, cinematic, and inviting.

Could you take us through the process of developing your documentary?

I originally planned to write an editorial. On a whim, I mentioned this idea to a friend of a friend who also happened to be a videographer. He convinced me that we should make a film together. It made all the difference that I had a filmmaker who really believed in me and my vision.

Before I started, I did around six months of research and interviewed about thirty academics from all over the world. At this point, I thought about the narrative I wanted to put forth. When I had a storyboard, I contacted the five academics that I felt best represented the discussion and would be most ‘camera ready’. Luckily, they were willing to participate, and after I wrote the questions, I interviewed them again on film. Meanwhile, I was also looking for grants and funding to supplement our shoestring budget. I built the interview clips into the storyboard, wrote the script, and then filmed the visual shots in London, Oxford, and Paris, supplemented with external footage.

We edited it all together, which took forever. (But we did it during lockdown so that worked out). We had a soft launch in August and submitted it to the festival circuit, where we won six awards. We’re now pushing it out, organising screenings, participating in panel discussions, and sharing it with you guys!

What were some of the main difficulties you encountered while working on The Return Address?

Summarising the debate! I really wanted to keep it under half an hour, so people could easily sit down and watch it. I was speaking to people who were highly educated and felt strongly about the topic, meanwhile in interviewing and scriptwriting I had to keep it as general and accessible as possible. While writing, I also had to be aware of how to talk about sensitive issues – carefully selecting language was crucial. What sounds okay from your perspective is not always the way a point should be formulated. I also wanted to make sure that terms with powerful connotations, such as ‘repatriation’ and ‘plunder,’ were defined with care so that we could have a meaningful conversation. In the film, I tried to invite the viewer to find their own way, letting the experts provide various arguments and using them as benchmarks for different viewpoints. I came to understand that as much as you are trying to educate people, you’re learning during the process as well.

In the end, you have to be really committed to make such a project work. If it is the right project, you will choose to do it over leisure time. I found it was quite easy to stay engaged in that sense.

What do you hope The Return Address and the Contested Histories project will achieve?

Ultimately, I hope we can reach a place where museums and urban spaces can be spaces where we engage with the truest representation of the past and where multiple voices are heard. There is still a lot of work to be done to incorporate all these voices in history. The people designing our museums and cities have a big job to do. Their task is to curate – to be the mouthpiece of all these different narratives. To include these narratives in the wider historical consciousness we need to begin with education – this is where I believe the Contested Histories project comes in. By presenting contested legacies in a nuanced way, the project gives us an informed start for including different narratives. However, curators and policymakers are not the only ones with a stake in the decision-making; I really believe in community driven initiatives, and I would certainly recommend involving grassroots movements and collaborative approaches to get us across the finish line.

Is there anything else we have not discussed that you’d like to voice?

I really feel that as much as it can be difficult to come up with opinions and answers to these challenging questions, this is not a conversation we should shy away from. Making mistakes is not something we should be afraid of. I would encourage and implore anyone working on the Contested Histories project, or indeed anyone who visits museums and passes through public space, to not feel that they are unqualified to have an opinion. We all make use of public spaces where we live, we all have a stake in our own cultural heritage. This is a discussion we all take part in every day.

Check out The Return Address: Where Does Heritage Belong on museandwander.co.uk/film and more of Issabella Orlando’s work on museandwander.co.uk, a platform for writings on travel and cultural heritage.