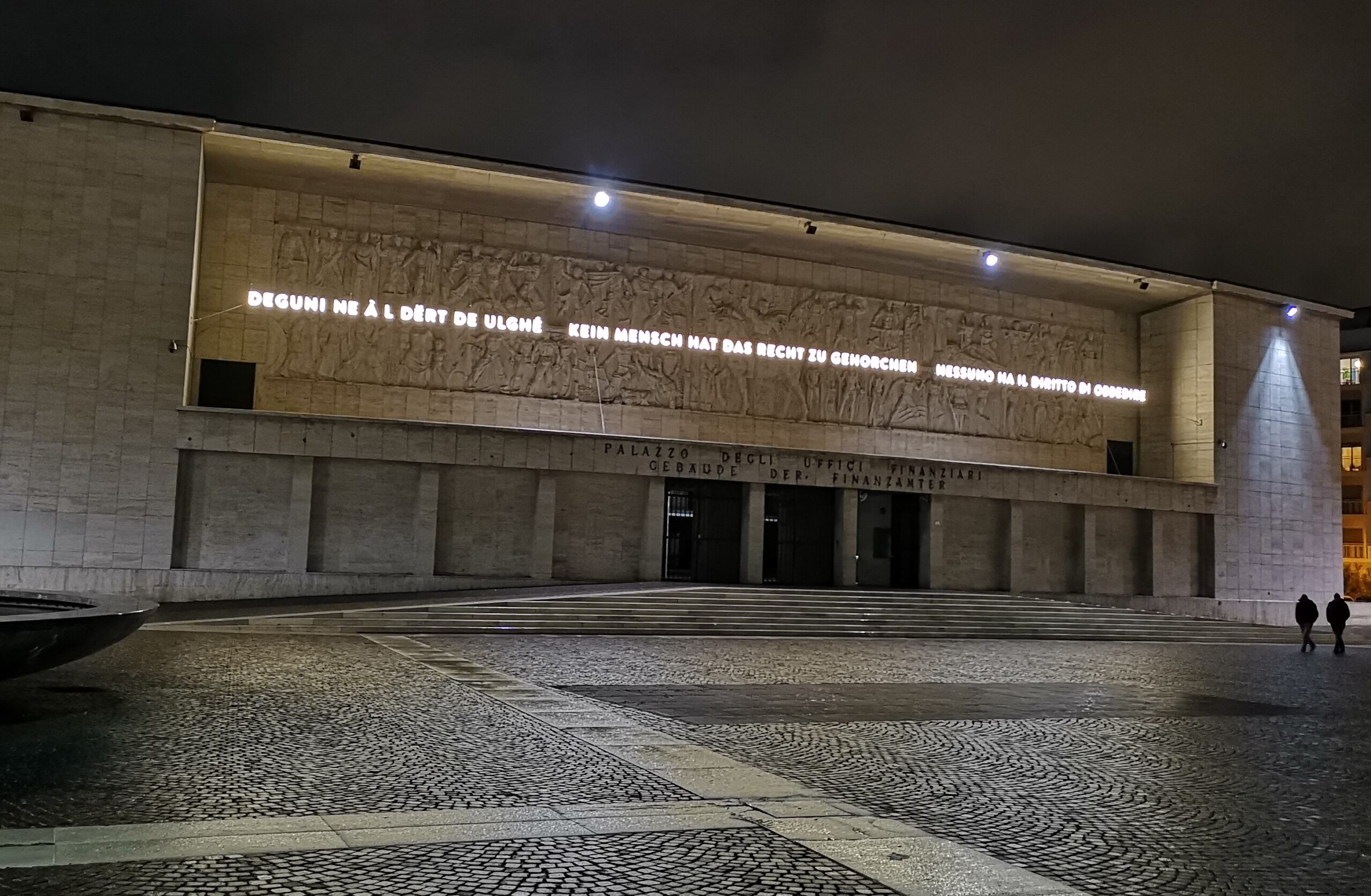

The beautiful mountains of South Tyrol, an autonomous northern Italian province bordering Austria, are inhabited by three different ethno-linguistic communities: the most numerous German-speaking, the Italians and the Ladins, a tiny minority speaking a Rhaeto-Romance language. Once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, South Tyrol was transferred to the Kingdom of Italy at the end of World War 1 and since then, like in many other multinational regions in Europe, the relation between the two main communities has been tense, at times even violent. Consequently, one would expect the teaching of history and especially local history, often intertwined with family history, to be challenging and controversial. However, as Giorgio Mezzalira explains, the situation has greatly improved in the last decades, and South Tyrol can now be considered an example for other regions divided by rising nationalisms and ethnic tensions.

Until his retirement last July, Giorgio Mezzalira taught Italian language, literature and history in a German-language secondary school in Bozen / Bolzano, the capital city of South Tyrol. Traditionally, pupils who spoke German as a first language attended German-language schools and vice versa, with the result that young people had few opportunities to meet their peers from the other community. The history curricula reflected the segregation of the education system: German-language schools taught the history of the German people and local history, while Italian-language schools focused on Italian history. The stress on the local dimension in the German history curriculum, which persists today, was due to the community’s attachment to their Heimat (a term that has no exact equivalent in English, and in this case would be a sort of rural provincial homeland). But history was important for everybody in South Tyrol and thus it was often exploited and manipulated for political aims. For example, those in the German community who wished to have South Tyrol reunited with Austria promoted a historical narrative according to which the cultural persecution of the non-Italians, started with Fascism, continued for decades after the end of the regime, thus implying that Germans could expect no fair treatment from the Italian authorities.

In the last decades, things began to change gradually but steadily thanks to the concerted effort of state and local authorities who worked to leave behind old divisions and create an inclusive society. Today, the school system in the province still envisages monolingual instruction delivered in German- and Italian-language schools, while in Ladin schools all the three languages are taught, but both German and Italian pupils are expected to acquire some competence in the respective second language. The public debate on the history of South Tyrol is finally depoliticised and left in the hands of professional historians from both communities who work together to create new narratives of the past free from partisan interpretations. Public investment in projects of dialogue and co-operation between the two communities has increased significantly, especially in the field of education. For example, a recently implemented scheme offers secondary school students the opportunity to attend one year in a school of the other community. The scheme has been very successful so far because, as Mezzalira says, “young people today are not only more curious about the other community, but also less keen to remain within the boundaries of their own”. According to him, segregation in education is slowly decreasing: in the last years, although most of his students spoke German as a first language, some of them were from multilingual families, and even from Italian families.

The political and socio-cultural evolution of South Tyrol have posed, and is still posing, various challenges to educators. For example, students spending one year in the other community’ schools must be adequately guided and supported to ensure their cultural and linguistic inclusion. In terms of curriculum, it is probably history the subject that has undergone the most radical transformation. All three kinds of school have seen a shift in history instruction from the national to the international dimension, with European and World history featuring prominently in textbooks. Local history too has gained more space in the curriculum, creating opportunities to increase students’ involvement and participation by including family memories into prescribed narratives. In fact, although students’ interest in the subject is not very high generally, they are keen to listen to the stories of their parents and grandparents at home, thus coming in contact with personal narratives of controversial events and periods before they learn about them in school. “Then when they are in the classroom, they either defend the version of the past they learnt at home, or they want to verify it”, says Mezzalira. Thus, it is up to teachers not only to present multiple narratives, but also to contextualise them and explain what purpose they may serve. In other words, teachers should encourage a critical approach to history in order to equip students with the necessary knowledge and skills to ask questions and to find answers independently. Although this can be challenging, history educators in South Tyrol are lucky enough to enjoy the support of local authorities and of the three offices (German, Italian and Ladin) in charge of the administration of education.

Since the province of South Tyrol is one of the richest in Italy, local administrators have taken advantage of their devolved powers to fund education generously. In particular, history education is seen as fundamental to the creation of future citizens thanks to its potential to foster dialogue. In order to equip history teachers with the necessary skills and knowledge to encourage debate and critical thinking in the classroom, the Faculty of Education of the local Free University of Bozen-Bolzano pays particular attention to multiperspectivity and to local history. The latter is generally given more space in German and Ladin schools where history instruction focuses on the relationship between centre and periphery, allowing educators to develop their teaching on the idea that the local dimension is functional to the understanding of national history. In support of this approach to teaching, Mezzalira and a few colleagues, in conjunction with the three offices supervising education in South Tyrol, compiled a multiperspective history textbook: Paesaggi e prospettive: lineamenti di storia locale: L’età contemporanea in Alto Adige/Übergänge und Perspektiven – Grundzüge der Landesgeschichte: Südtirol seit 1919. The textbook narrates the main events of the last 100 years of history of South Tyrol from the points of view of the two communities. Although not many didactic activities have been developed so far to help teachers use the textbook, it remains a major achievement and it has been chosen by several schools.

In conclusion, South Tyrol can be considered an example of good practice in dealing with an ethnically and linguistically divided society. As social scientists highlight in their studies of the devolution of power to South Tyrol, local authorities have made the most of their autonomy from the central government by investing substantial resources not only in the economic but also in the social development of the province. This has gradually limited political interference into the public debate about history and given more space to historians from different backgrounds to collaborate and create the above mentioned textbook. However, as Mezzalira warns, this tool is not an antidote to social divisions: “There are not shortcuts. South Tyrol became ready for such a textbook thanks to the many years in which the two communities slowly started to come together. Then the authorities stepped in to identify and use those experiences of dialogue that were already growing. Feeding such projects created the basis on which new opportunities of encounter and collaboration between the communities could be built, eventually spreading the change”.