“If you’re going to teach history, teach it all” (Paolo Ceccoli, EuroClio Ambassador)

During the final workshop of our Annual Conference, EuroClio ambassador Paolo Ceccoli shared this powerful quote. The goal of the Marketplace on Contested Cultural Heritage was twofold. On the one hand, participants learned about the research that EuroClio and the Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation (IHJR) have been doing to study contested histories in public spaces. On the other hand, the marketplace was an opportunity for participants to reflect and share lessons learned during the Annual Conference.

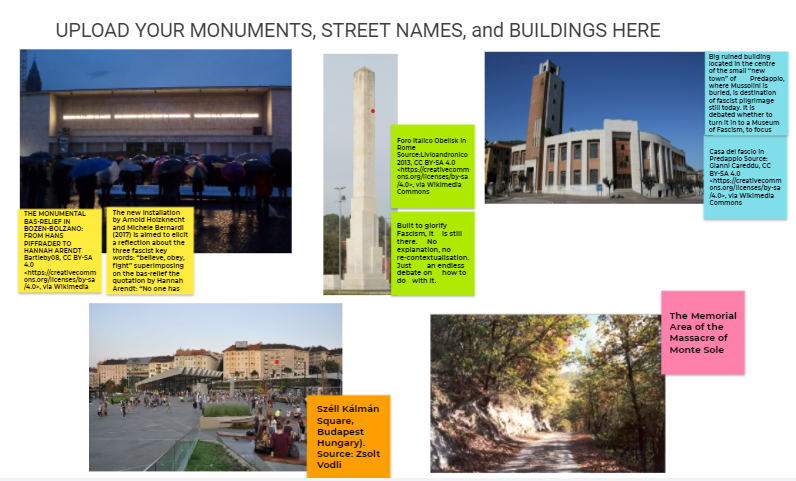

Drawing on more than 230 case studies from Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas, the Contested Histories project seeks to identify underlying causes for disputes dealing with monuments, memorials, statues, street names and other physical markers of historical legacies in public spaces. The objective is to provide decision-makers, policy planners and educators with a set of case studies, best practices and guidelines for addressing historical contestation in an effective and responsible manner. As director Marie-Louise Jansen mentioned during her presentation: “Understanding root causes [of controversies] necessitates a multi-perspective approach”.

The conference focused on controversy and disagreement in the classroom. At the Marketplace, the different teaching strategies presented throughout the month of November were applied to examples of controversial cultural heritage within the local context of the participants. Cases from across Europe were discussed and compared; the difficulty of addressing colonialism in Spain, the centralised curricular system in Ukraine preventing multi-perspectivity, the tensions and polarisation in Croatian classrooms over identity and narratives of the recent past and the legal difficulties of contextualizing or removing statues in Slovakia due to property rights are just a handful of examples mentioned by participants during the session. All participants could name an example of a contestation, either directly in their classrooms or in their countries’ public spaces.

While the issues educators face are distinct, the themes are similar. Paolo Ceccoli mentioned: “the more our societies are divided, the more history teaching should teach controversial issues, it’s not easy, … can even be dangerous, morally or even physically, but it’s absolutely needed”. The importance of contextualization was often emphasised as was the power of comparative studies. Another suggestion was the initial depersonalization of history – shifting personal feelings of guilt or blame that inflame emotions and prevent self-reflection – allowing for multiperspectivity. Another EuroClio expert Benny Christensen put a recommendation very simply: “[When dealing with controversial histories], apply the three D’s: Discuss, Debate, Dialogue”.

Interested in a concrete example of how to teach about controversial cultural heritage? The Rhodes Must Fall Oxford content on Historiana offers a great introduction.

Call for images: photographs documenting disputes are central to our research and the team is often constrained by images that are copyrighted. If you have an image of a contested monument, street name, statue or other physical representation of historical legacies in public spaces, please share them with us! Appropriate credits will be given.

For more information and to share images, email info@ihjr.org.