This report of a study visit to Cape Town, South Africa, is the first in a series of reports and blog posts on Dealing with the Past in History Education. An in-depth discussion of the visit to South Africa, written by Michael Robinson, is available here. For more information about the project, visit the project page: Dealing with the Past in History Education.

On March 1st, 2017, Michael Robinson and I arrived at one of the most beautiful cities in the world, Cape Town, South Africa. This visit was meant to start our study about peace making in one of the model countries, “Dealing with the Past in History Education”.

My first day wasn’t very fruitful. Our contact, Mr. Cecyl Esau, and I were shocked because our first interview was canceled by a voice note after we had waited two and a half hours for the representative of Robben Island to attend the meeting, which was prescheduled by Mr. Cecyl. This limited the study visit to one interview, and we missed important information about how Robben Island was transformed from a prison to a peace figure.

On our second day, March 2nd, my colleague Michael and I conducted our first interview with Mr. Ceycl, Senior Project Leader for Building Inclusive Societies at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR). We had a beautiful and detailed introduction from him about South African history and the huge shift from the apartheid to democracy. He talked about the efforts given to ensure that these changes were made. One of the most beautiful examples of Mr. Cecyl’s interview is detailed in Michael’s blog report, which talks about a lady who told her daughter to make way for the uncle.

After this interview Michael and I went to the South Africa Jewish Museum and Holocaust Center. The museum is located just across the street of IJR. We took a small tour, trying to find something that could have been related to our visit. For me it was my first time ever being this close to the holocaust tragedies. After our self-guided tour, we met Roz von Zaiklitz, a guide from the museum, and she shared with us her story in South Africa, which can be found in Michael’s blog report. It is a very interesting to read.

When our break was over we went back to IJR to meet with Lucretia Arendse for a half hour. It was a very good interview; Michael wrote about it in his blog report. Lucretia is the project leader for education and reconciliation to promote peace education in South Africa. Her team develops history resources about the transition of South Africa from apartheid to democracy. Their work started by looking through the history curriculum and trying to find out what was really working in the history classrooms and what acts of discrimination were happening. They also examined how they were dealing with what was happening in the classrooms, and if the teachers had special methodologies of their own to deal with discrimination. After starting this project with the cooperation of UNESCO, they were triggered by the following question: As a teacher, when he/she steps into the classroom, how will he/she teach while having to deal with his/her own wounds? This raised another difficulty, so they decided to create a workshop to train teachers on how to deal with these wounds in the classroom. Lucretia thinks that people who are working are doing an excellent job, but still, when they look in social media they find out that they have more work to be done.

In the Afternoon of the same day we met with Mr. Dylan Wray, the executive director of Shikaya. Dylan introduced himself as a former history teacher, who then quit teaching to start writing history curriculum and training history teachers on delivering it in ways that allow children to leave schools as active, democratic, and caring citizens.

He also clarified the aims of the project, which are meant to allow teachers to teach about the apartheid to those who lived the apartheid. In spite of his efforts, he mentioned that there are some difficulties and challenges facing his project. One of these difficulties is that in some schools, teachers are assigned to history teaching. This makes training the teachers in some ways difficult, since they are forced to teach the subject. Another challenge facing him is that students drop out of schools in large numbers, and Dylan thinks it is hard to reach them to ensure they’ll become active and compassionate citizens. Feel free to read the nice passage Michael wrote in his blog report on this topic, especially the part which talks about “classes of hope”.

When the meeting with Dylan was over, Michael and I headed back to our room where we made a deep reflection on our day, and we both agreed that we had good interviews including the unscheduled one to the Jewish museum. We thought we had a good idea about the efforts the NGOs are trying to put into dealing with the difficult past or into the development of history teachers and resources.

After our reflection, it was the time to discover the natural beauty of Cape Town so we visited one of nature’s wonders, Table Mountain. I think anyone would regret visiting South Africa without going to this beautiful site. There one can discover the beauty of the place and the peace it gives to the soul.

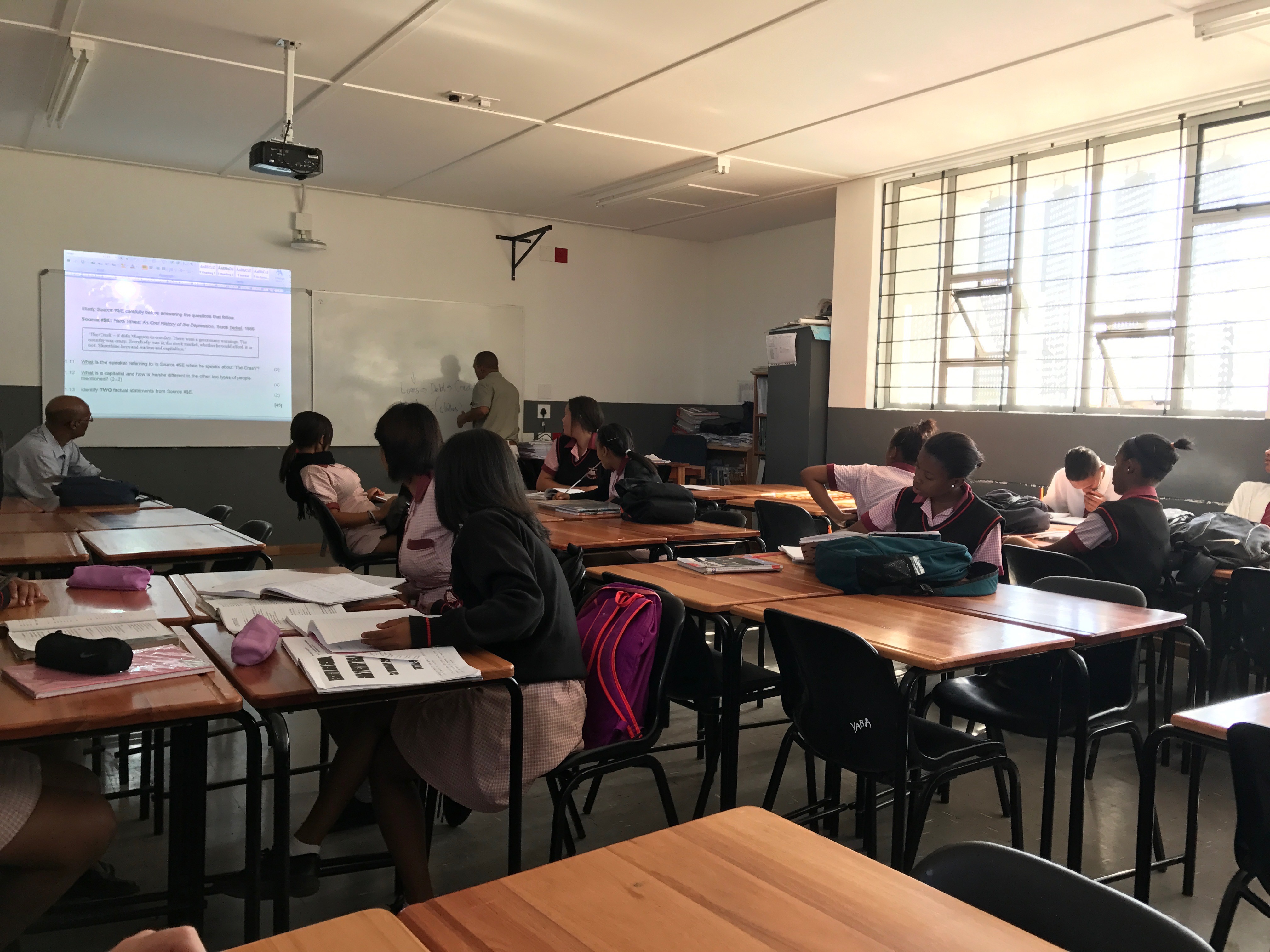

3rd of March, 2017, was a new day with a different schedule. It was the time for the team to visit a school. Our major goal was to get interviews from history teachers and then students. We wanted to discover what is taught in history classes, and how history teachers are helping to face the difficult past. These interviews will give us clear ideas and answers from people who are directly concerned with history education.

We were close to not being able to conduct the visit, especially after the delay of the official approve to our school visit request. But luckily Mr. Cecyl received the permission to visit one of Cape Town’s high schools, Kensington High School. It was around 20 minutes’ drive to the school, and were sad to know that we couldn’t stay more than an hour and forty-five minutes in total. This time frame was very challenging for us to get good interviews from students and teachers, before we were scheduled to do the other visit of the day to Robbin Island.

Getting back to the Kensington High School visit: I had this feeling that the school’s principle and history teacher didn’t have any idea why we were visiting the school. They thought we want to monitor a history classroom and get ideas about the teaching methods and strategies used for history teaching in South Africa.

So after spending some time viewing the lesson; which gave us some ideas about the history teaching there, we asked the teacher if it would be possible to interview some of the students and then himself. He agreed to our request, and three of his students volunteered for the interviews. A fourth student, Paola, asked us if she could join in, and she got our permission.

First we asked the students why learning history was important to them from their own perspective. They thought that learning history would teach them about their past, where they came from, and how they become who they are.

Then we asked the students what the word “apartheid” meant to them, and they replied that some of the people were still segregating others by their color. They thought that all people are equal and it isn’t fair to judge others because of their color.

We asked them about history education and if it is helping to overcome this racism and segregation. Paolo, one of the interviewed students answered that it actually did help, qualifying his answer by saying that the help is mostly directed to the students’ generation more than their parent’s generation, because the students are going to schools and interacting with others.

After that we started interviewing Mr. Shaun Rossou, the only history teacher at the school. He shared his feelings and memories from when the apartheid was over. He still remembers when Nelson Mandela was declaring the beginning of the new era for South Africa. He also talked about teaching of the apartheid in the history curriculum.

Students learn about the apartheid in different grade levels, but most of them work on projects about the apartheid as grade nine students. They have to work with their parents or close friends who lived during the apartheid and get their perspectives about one of the apartheid’s laws. And due to the fact that parents are becoming those who didn’t live during the most “brutal” part of the apartheid laws, as he described it, students now are working with their grandparents or other elders who lived during that era. Some of them came back with their grandparents pass book or “Dom Pass” as they called it during the apartheid. The “Dom pass” was to be carried by all non-whites, and the non-white individual with no pass would get into trouble.

This was our last interview at the school. We wished we could be there longer, but it was time to visit Robben Island.

Standing in a long line to take the boat to Robben Island, Michael and I were excited to get there and witness the history of this memorable island. The whole trip took us less than five hours, but to be honest it was worth it.

On the island there were buses waiting to pick up the tourists to start a guided tour showing them the different sites such as prisons, churches, schools, and the high commissioner residency. For me the most emotional site was the prison, through which I went on foot. A former prisoner narrated his story of his time on the island. He shared stories of the prisoners and himself and how they were treated in savage ways. He also told stories of how the jailers tried hard to separate them from Nelson Mandela by cheating the system. In spite of all of this, when everything was over and a new system was born, the prisoners had to forgive those who treated them badly and had to live with their oppressors to build a new era for South Africa. This shows how big their hearts were, and the honest efforts they were making.

On the way back we stopped for some lunch at the sea line, and then we got to the hotel to evaluate our day. We came to the conclusion that the Robben Island trip was an excellent one, though it would have been better if we could have met some of the former prisoners in person, or if we had had a personal guide to share with us the success story of this island being turned into a peace model. Regarding the school visit, we both agreed that it would be better to visit more than one school from different sectors or towns as well. We thought that perhaps these visits would provide us with different narrations from different perspectives. At the end of this day, the best lesson I witnessed was that of the brave forgiving heart. It was the time to get ready for our next day visit.

District Six was our last destination on that study visit to South Africa. We met with Ms. Mandy Sanger, the museum’s Education Manager, who introduced Michael and I to the museum’s brief history of the district and its peaceful message, which Michael included in his blog report. Mandy shared with us how people were forced to leave their homes and their properties. Beautiful pictures are hung on the museum walls showing real sites from the old district before it was declared a white area. Mandy thought that the most important purpose of the museum was to educate people, and mainly students, about what the apartheid was so they’ll never go back to it. The museum continues to provide workshops, discussions, conversations, and other methods for delivering or sharing stories about the apartheid with museum visitors.

We also met Mr. Joe Schaffers, one of the museum educators. Joe was born in Bloemhof Flats, District Six. He lived for 28 years in the district before being moved out of it because he “didn’t qualify to live there anymore” as he said. He gave us a brief testimony for what he witnessed at that time, concerning himself and his neighbors.

After this visit was over we headed to the hotel where Michael was traveling from that day and I was staying for the next day.

This report of a study visit to Cape Town, South Africa, is the first in a series of reports and blog posts on Dealing with the Past in History Education. An in-depth discussion of the visit to South Africa, written by Michael Robinson, is available here.