When you stand on the Svatopluk Čech Bridge in Prague, you find yourself caught between different layers of the city’s history. Behind you lies Letná Park, while ahead you look straight into the older Jewish quarter of the city. These landmarks reflect significant periods of Prague’s history, but one period, the Communist era, does not seem to be directly in view. That’s because its most striking symbol in this part of the city, a massive Stalin monument, was demolished more than sixty years ago.

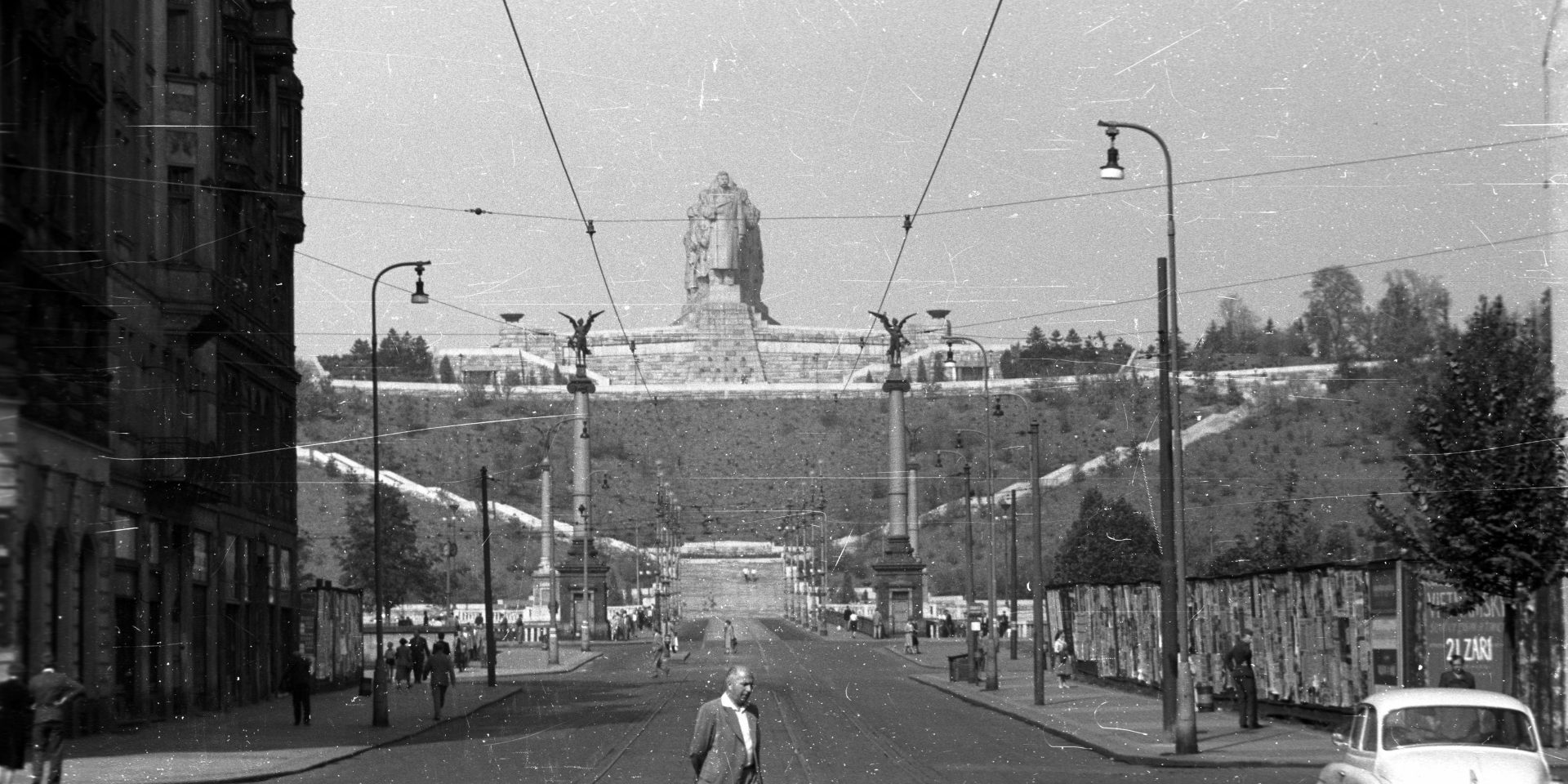

Commissioned by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in 1948, the monument was the product of a competition for visual artists in Prague. Otakar Švec won the competition, and over the course of five and a half years, his design took shape: a colossal stone statue measuring 15.5 meters in height and 22 meters in length. The construction was completed through the use of forced labour, with labour camps situated around Letná Park. While Stalin was featured at the front of the monument, he was surrounded by other figures who, quite literally, supported him. These other figures represented ideal members of socialist society: workers, farmers, party members and soldiers.

The finalised monument was unveiled on the first of May 1955, May Day. The unveiling was part of a big ceremony, which served as a testimony of Czechoslovakia’s loyalty to Moscow. Yet the monument only stood for seven years. As the political climate shifted and the process of de-Stalinization began, the statue quickly became an eyesore. The party ordered the demolition of the monument in 1962, which turned out to be a complex task as the monument weighed around 17 million kilograms. In the end, 800 kilograms of explosives were needed, while the cleaning of the consequent rubble took months. Not only was the demolition a complicated undertaking due to the monument’s size, it was also challenging because it had to happen discreetly. A statement was issued that all photography of the demolition was prohibited, but sculptor Josef Klimeš defied the order, capturing rare images that survive to this day.

Today, not many traces of the monument remain, both physically and in collective memory. Yet its story is telling. It is a story that shows how significantly landscapes and cities could change under Communist rule, and what these changes meant for the local population. It is also a story that shows the changeability of the Communist Party’s demands, and the pressure this puts on society. On top of that, it highlights the environmental costs of ideological expression. It is also a story that gives us a look into the use of symbolism and tradition in propaganda, which shaped public space and national identity.

Within the project Making Visegrad Histories Digital, we explore stories like this one. Stories that may seem unusual or have been ignored, but that tell the story of the Communist era in all its versatility. Alongside specific case studies like that of the Colorado Potato Beetle or that of Daňa Horáková, the project offers a broader historical context, helping students and educators deepen their understanding and teaching of the lived reality under Communist rule. Are you curious to know more about the use of resources during this time? The level of propaganda that spread throughout society, or the difference in May Day celebrations between different socialist countries? Keep an eye on Making Visegrad Histories Digital for upcoming resources and tools that can be used in the classroom.