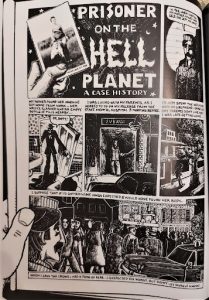

Maus is a graphic novel by Art Spiegelman, serialized from 1980 to 1991 and divided into “My Father Bleeds History” and “And Here My Troubles Began”. As the subtitle indicates, the book is “A Survivor’s Tale”, telling the story of Spiegelman’s father as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor.

Maus is a memoir, the chronicle of a family, a piece of art where writing and visual techniques are deployed to raise awareness, condemn, explain, keep the memory alive. With Maus, Spiegelman debunks the myth that the Holocaust outfaces the artistic imagination and shows us how storytelling and visual arts can teach us remembrance and give us a unique historical perspective.

The medium

Spiegelman addresses the problem around the representation of the Holocaust by choosing to adopt the comic strip form, which turns out to be a key element through which he manages to successfully blend words and pictures, past and present, history and remembrance. More specifically, he decides on a frame tale made up of black-and-white panels, purposely using a rather simple style that clashes against the complexity of its content and the delicate issues it faces.

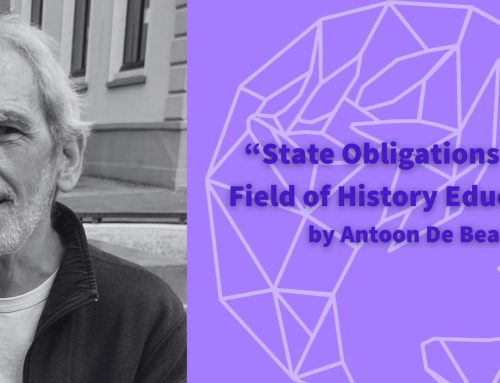

The choice of the medium is relevant as Nazism itself had its own aesthetic stance: art was the expression of totalitarianism, the rationale behind it, and the medium through which to celebrate perfection in form – a perfection which was embodied by the purity of bloodlines. In order to spread the idea that Jewish people were an inferior race, the Nazis hung posters in the streets that showed the Jews as rats and mice.

As an epilogue to chapter one, Spiegelman includes a quote from Adolf Hitler: “The Jews are undoubtedly a race/ but they are not human” (Spiegelman, 10). And so the author purposely introduces animals, the ‘not human’ to tell the story: Jews are not portrayed as people, but as mice, vermin that must be destroyed for perfection to flourish, for nobler races to prevail. He also portrays the Nazis as cats, the Poles as pigs and the Americans as dogs.

(Spiegelman, 56)

As this picture shows, the Holocaust survivor Vladek, turned into a mouse, says: “I’m not going to die, and I won’t die here! I want to be treated like a human being” (Spiegelman, 56). The character of Vladimir is drawn as an animal to give specific form to stereotypes and yet affirms its humanity and demands to be treated ‘like a human being’.

Telling a story “the way it really happened”

At the very end of chapter one, there is one specific passage that functions as some sort of premise and that makes the reader reflect on the relationship between past and current history, between memories and storytelling:

“I don’t want you should write this in your book.”

“What? Why not?”

“It has nothing to do with Hitler, with the Holocaust!”

“But Pop – it’s great material. It makes everything more real – more human.”

“I want to tell your story, the way it really happened.”

“But this isn’t so proper, so respectful.”

…I can tell you other stories, but such private things, I don’t want you should mention.”

(Spiegelman, 25)

Despite his father’s requests, Spiegelman does not just tell his father’s experience in the concentration camp. The comic also portrays him and his father making conversations, describing what they were doing and talking about. These in-between moments occur frequently: by interrupting the telling of Vladimir’s story, they remind the reader of the temporal distance between the moment of the characters’ conversation and the time his father is talking about. By doing so, they also bring the reader back to his own present, reminding him/her of the temporal distance between the time when the graphic novel was written and the historical moment it is set in.

The Holocaust happened far away in time and no one can tell ‘what really happened’, but it is nonetheless our duty as human beings to remember and to make sure generations bear the memory of it. Spiegelman does not ignore the fact that these historical events happened a long time ago – instead, he sheds light on the fact that memory is not something stable, but rather subject to change: how people remember things might differ from time to time, and so might those feelings, emotions, perceptions attached to it. Including details about his father’s pre-war life, deciding to retell ‘such private things’ is vital to remind the reader of Vladimir’s unique point of view. In this sense, the story’s purpose aligns with its subtitle: Maus can only be the story of a survivor, and it does not even attempt to describe the complete history of the Holocaust, which would necessarily be an unattainable goal.

Spiegelman knows he might fail in the act of retelling the story of his father: he can reach neither an authentic drawing – hence the animals, inhabiting the space of fiction – nor an authentic version of the story, as he did not experience the Holocaust himself. His work cannot do justice to ‘what really happened’. The novel promotes the idea of a “fictional truth”: the survivor’s tale is the truth of him having experienced the Holocaust, but storytelling lies in the realm of fiction. The act of remembering is an ongoing process that constantly pushes the remembering further and further away from the remembered. The comic strip form and the images are the key elements to portray and convey the interruption of time and memory.

Here are a few examples of how the comic form, drawings and photographs are used in the novel.

The interruption of temporality

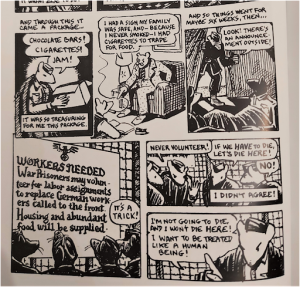

(Spiegelman, 47)

In this picture, Artie is lying on the floor, writing in his notebook while talking with his father: at first glance, it seems to be an image of the present within the story. On closer inspection, Artie’s legs are not in the living room but spread into the image of Vladek in the past, in 1939. Artie’s body becomes the connection between past and present, fused as one.

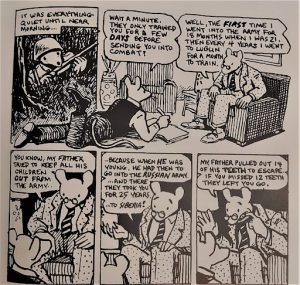

(Spiegelman, 102)

Another fusion between past and present comes in the form of a comic within the comic, the autobiographical “Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History”. It is a comic book drawn by Artie to process the painful loss of his mother, who committed suicide. The comic book has a style of its own: the characters are not drawn as mice but are kept as humans. Spiegelman inserts an old photograph of himself and his mother, but in this case, the drawings seem more realistic. Artie and Vladek look like skeletons: they have dark faces and look extremely thin to highlight the tragic impact that the event had on their life.

The comic strip form allows the author to visually represent multiple temporalities: there is a thumb holding the photograph in the top left corner, but also a thumb holding the comic in the bottom left-hand corner. This is another distancing strategy used by the author: the reader is simultaneously viewing someone else reading the book, and at the same time made aware that he/she is viewing himself/herself. The temporality of the text is visually amplified.

Making a timeline: processing memories

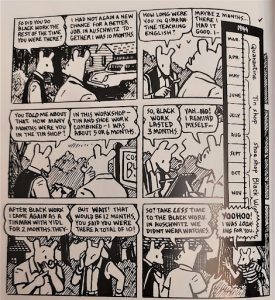

(Spiegelman, 228)

Spiegelman seems to attribute a therapeutic power to comics and storytelling, and to all the arts in general. In the book, Artie drew a comic to deal with the trauma of the loss of his mother, and he is currently drawing another comic to do justice to his father’s experience. Not only can art help to process memories but also overcome those traumatic ones.

In the example above, Artie is trying to make sense of Vladek’s story by making a timeline, determined to make order between events. This idea of making sense is a feeling that comes across quite strongly, and it is the cause of great frustration because reconstructing an exact timeline is not possible. Vladek seems quite pissed at his son, and he remarks: “In Auschwitz we didn’t wear watches”, hinting at the fact that time was somehow suspended in the concentration camps and the only time people could know of was the present, perhaps implying their lack of hope towards a different future.

As a storyteller, Artie is obsessed with giving a logical frame to those events. However, Spiegelman reminds the reader that our memory is fallible and that it is precisely that inexactness that makes storytelling similar to the workings of our memory.

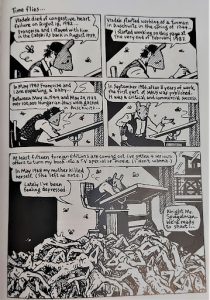

(Spiegelman, 201)

In this case, Spiegelman is interrupting the temporality of the text by picturing a plausible future: he is imagining his book has become a commercial success that has commodified his father’s story. Instead of being drawn as a simple mouse, he is wearing a mouse mask and, talking from the top of a mountain of Jewish dead bodies, he admits he is feeling rather depressed.

Photographs: documenting history, representing post-memory

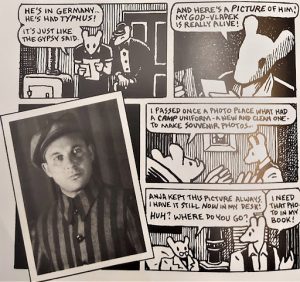

(Spiegelman, 165, 294)

In total, the viewer is faced with three photographs. The first photograph is the one of Art and his mother, the second one portrays his brother Richieu, and the third one is of Vladek, inserted only at the very end of the novel. The photographs are used to represent the historical truth, the proof of Vladek’s tale. Maus is a work of fiction, but one of historical fiction, where the drawings and more broadly the comic strip form purposely connect the past to the present. The photographs work towards a glimpse of the history that took place. They represent both historical documents insofar as in them lies the proof of this family’s existence, but they also represent post-memory as Spiegelman has inherited memories that have had a great impact on his life.

Why should it be included in history education?

This graphic novel can be used in the classroom to teach about the Holocaust, remembrance and the concept of post-memory, as it tells a true story and it shows the interconnectedness between past and present.

In need of more inspiration and tips for how to include Maus in your teaching? Have a look at the many existing resources such as the Teacher’s Guide produced by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, the accompanying teacher’s guide by Penguin Random House, and the Museum of Jewish Heritage Curriculum Guide.

Written by Giulia Verdini

| Related articles

For history educators who are interested in incorporating novels into their teaching… -Find out how comics can be used in the classroom. -Learn how literature and reading practices can turn your students into historical actors. -Decolonise your teaching practices and foster multiperspectivity with Nella Larsen’s ‘Passing’. |

Bibliography and Suggested Readings

Costello, A. Lisa. “History and Memory in a Dialogic of “Performative Memorialization” in Art Spiegelman’s “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale””. The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association. Vol. 39, No. 2. Midwest Modern Language Association. 2006. pp. 22-42.

Ewert, Jeanne C. “Reading Visual Narrative: Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”. Narrative. Vol. 8, No. 1. Ohio State University Press. 2000. pp. 87-103.

Doherty, Thomas. “Art Spiegelman’s Maus: Graphic Art and the Holocaust”. American Literature. Duke University Press. 1996. pp. 69-84.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory”. Discourse. Vol.15 No.2. Wayne State University Press. 1992-93. pp. 3-29.

Spiegelman, Art. Maus. London: Penguin Books. 2003.