History educators like learning history and want to know more. They also believe that history education is key to become responsible and active citizens. These are, at the end of the day, some of the main reasons that pushed them to pursue a career in history (and citizenship) education. Students, on the other hand, often do not choose to learn history. The majority of them follows history as a compulsory school subject, failing to understand its relevance and often finding it boring or, in some extreme cases, useless.

How can we better engage students in history? How can we make history teaching meaningful for them? It is with this questions in mind that the participants to the 26th EuroClio Annual Conference approached the Discussion Tables on Friday 05 April.

The tables, led by 5 EuroClio Ambassadors and Friends, dived into five different aspects of how to make history teaching meaningful for all students. They were characterised by exchanges, discussions, and proposed a series of concrete solutions and approaches to history in the classroom.

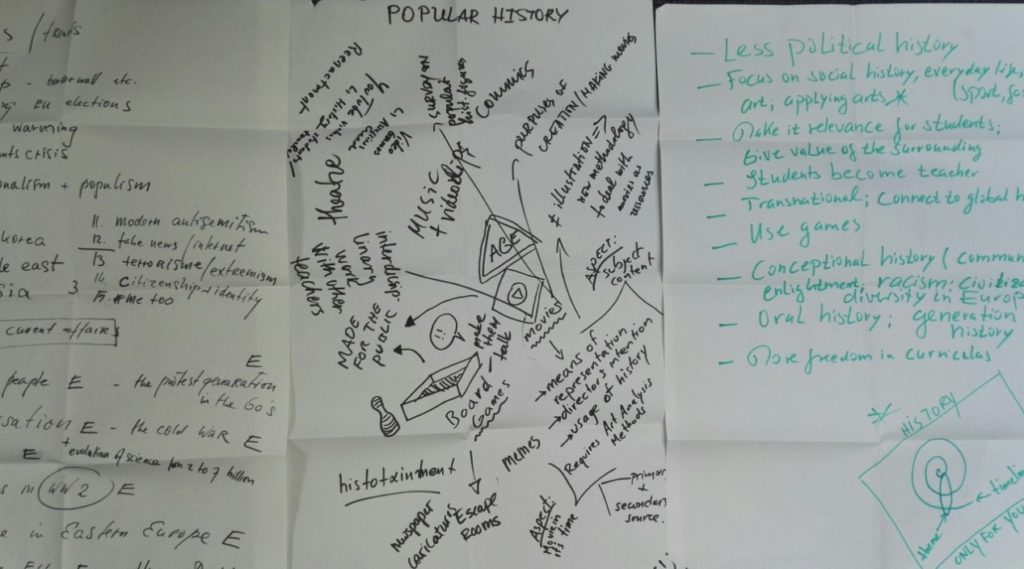

How to approach (European) history in an innovative manner?

How to depart from the classical frontal lesson or group work, to better grasp students’ attention? Focusing on this question, participants agreed that they would like to depart from political history, which is often considered boring by pupils. Many alternatives were suggested, including:

- Social history and everyday life

- The history of concepts (such as racism, civilisation, or diversity)

- Oral and generations’ history

In this way, participants argued, students would be able to feel the history taught in the classroom as theirs, and will feel more engaged.

Participants also agreed that there are, in students’ everyday life, special hooks that can be used to connect to history. For example, students might be interested in fashion or in sport. Referring to the history of a specific trend, or to the life stories of some players, could create the opening teachers were looking for to tackle historical events.

How to make the most of artefacts’ use in the classroom?

The use of historical artefacts in the classroom was identified by participants as one of the many possible approaches to make history education more innovative. However, it is not a straightforward approach: it is not enough to bring an object in the classroom and ask students to reflect on it. The interpretation of an artefacts’ meaning requires a particular skillset.

For this reason, a proper use of artefacts is subject to cooperation between students, teachers, and museum curators. Each one, in fact, brings a different approach to the object, thus making the analysis more complete.

The use of artefacts is particularly suited to touch upon the topic of the history of ordinary people, which has been frequently referred to during the Annual Conference.

The uncapped potential of popular history

Popular history, an approach to history that appeals to the wider public by means of media, games, and literature, has an untapped potential to bring history to life. Participants listed a series of popular history means that can be used in the classroom. This list includes:

- Movies

- Board Games

- Comics

- Theatre plays

- Video Games

If all these means could help engage students in history education, at the same time it is important to equip pupils with the knowledge and skills necessary to fully comprehend the topic at hand. For this reason, it is important to treat the material as resources, that have to be objectively analysed and contextualised. This can be done, participants argued, by promoting an interdisciplinary approach to the game or visual at hand, asking for example art teachers to participate.

Where were ordinary people? How did they react?

Where there ordinary people in the middle ages? How did the Solidarity Movement influence the life of 16-year-old students in Gdansk? These and other questions are of high relevance for students during history classes. Starting from these questions, it is possible to grasp students’ attention and not only introduce historical events, but also develop skills such as historical empathy.

The life of ordinary people can be brought to the classroom in many ways. For example, by means of the analysis of primary sources such as letters or diaries, when available. Another technique warmly recommended during this session was the use of interview, in which students are tasked to ask each other, a parent, or other possible interviewees, about the five events that had the biggest impact on their lives.

Finally, it was also suggested to reverse the question and ask students: how did ordinary people impact on big events?

How to react to history in the making?

Building on the panel on history in the making, teachers also discussed how history can best be linked to current affairs. To do so, they proposed a straightforward approach to the matter. First, they said, you should list all the current events that qualify as history in the making. Then, you can build parallels between these and past events. This parallel, participants proved with a brainstorming, is easy to draw, and connects current events to parts of the history curriculum.

For example, participants listed as cases of history in the making:

- Global Warming, connected with the history of industrialization and with the protest generations in the 60s;

- The migration crisis and the history of asylum seeking during the Second World War;

- Brexit and the upcoming European elections connected with history of the European Union.

At the same time, participants across all the tables agreed that, to carry out the approaches mentioned, they would have needed more time to prepare the lessons, and a certain degree of freedom in choosing their own curriculum. They also underlined the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, that can further help students to develop historical and critical thinking skills.

The discussions originated in the discussion tables became recurrent throughout the conference. Topics were touched upon again during workshops, and additional concrete answers were proposed and agreed upon.