In early November, the Bronbeek Museum hosted a day-long conference, sponsored by the National 4/5 May Committee of the Netherlands on how to teach decolonisation in former empires. Ethan Mark, a modern Asia historian from Leiden University, was there and shared the following insights with EuroClio highlighting the themes and outcomes of the day.

Oscar Van Nooijen from the International Baccalaureate was also at the event, and made detailed notes (available here), that also provide a useful and insightful overview of the context of Ethan’s piece, with an outline of the content of the various speeches and workshops that took place at the event.

Teaching the Ends of Empire

Empire: In today’s Europe, there is nothing so implicit and yet somehow less explicit. From the streets to the stock exchanges to the very categories and hierarchies through which we think, in the Netherlands as much as anywhere, the colonial empires and their legacies are everywhere. Yet if there was one takeaway message of a remarkable day of lectures and workshops on the teaching of “War and Decolonization in Netherlands-Indies/Indonesia,” hosted by the Bronbeek Museum and sponsored by the National 4/5 May Committee this past November 3rd—all the more remarkable for the presence of education experts from neighboring countries who provided a fascinating comparative perspective—it was the shared experience of a yawning gap between the ubiquity of empire in our histories and presents on the one hand, and a general unease and reticence when it comes to confronting empire in our school curricula and in our thinking more generally on the other.

In her opening address to the morning’s plenary session, Chair of the National 4/5 May Committee Gerdi Verbeet sensitively set the tone with a personal anecdote that highlighted the political fault lines perennially running through Dutch reckonings with their former colony and its ending in the bloody decolonization war of 1945-1949. She recalled how she and her classmates in high school in the early 1960s had often called upon their history teacher, a certain Mr. Mulder, to talk about his personal experiences in the Netherlands Indies, a place to which he was still so romantically attached that once he got started, he lost all track of space and time, thus freeing the students from boring obligations like following the standard curriculum or taking exams(!). More than a decade after the fact, her teacher still blamed the loss of the colony on Indonesian nationalist leader Sukarno – who he condemned as a “communist” – and on the “meddling” of the United States, which had backed Indonesia’s independence bid in the U.N. For Verbeet, who grew up in a socialist milieu (and more recently represented the [left-leaning] PvdA party in the Dutch parliament), it was not hard to recognize in her teacher a partisan apologist for a Dutch imperialism she had been raised to see as wrong. But she also noted that the views of a classmate who was son of a former member of the Dutch colonial army or KNIL (staffed predominantly by local minorities such as Molukkans, Ambonese, and people of mixed Dutch-Indonesian descent or “Indo’s”) aligned rather more closely with those of her teacher. And at home her own father, meanwhile, preferred to avoid the subject altogether. Sent to Indonesia in 1947 to participate in what were euphemistically described as “police actions” and “expecting to be greeted there as a liberator,” he had instead experienced horrors “that he never talked about to anyone in the family.”

As Verbeet noted, such traumas and contrasting, competing perspectives and investments have made it difficult for the Netherlands to come to terms with its colonial history, above all with the violent nature of its ending. In the school curriculum, and in the wider society, the predominant narrative of the Second World War for the Dutch has remained the “easy,” black-and-white one of victimization at the hands of the Nazi Germans “at home” and, to a lesser extent, at the hands of the Japanese in Asia. The “grey areas” in between the black and white, or even the possibility of a role-reversal implied in acknowledging a Dutch role as victimizers in colonial Indonesia and its violent ending—the latter recently highlighted for example in a well-received study on the Dutch military’s systematic use of terror tactics by scholar Remy Limpach—have up to now been largely avoided.

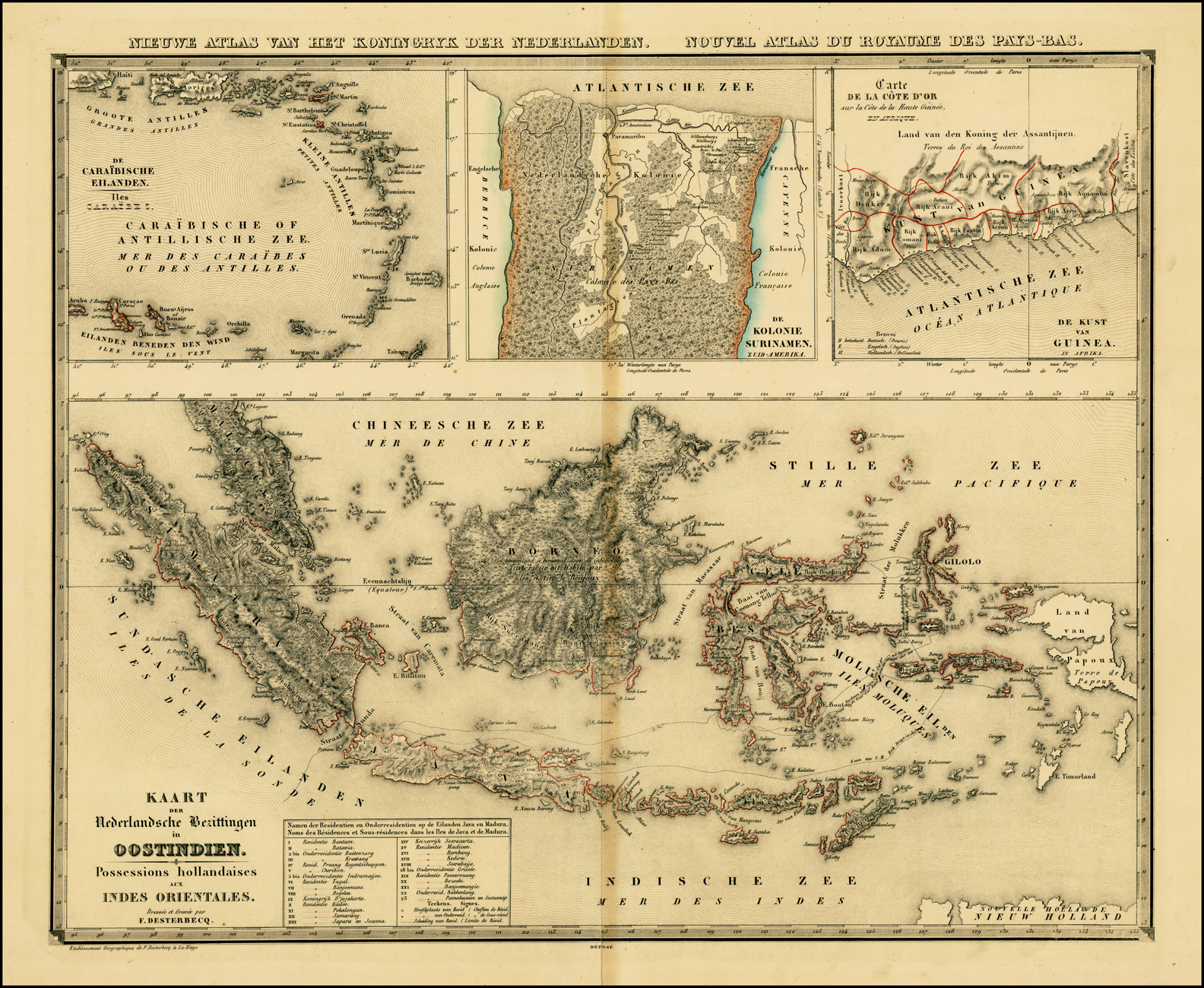

As Professor Remco Raben (University of Amsterdam, Utrecht University) observed in his subsequent keynote lecture “Colonial Past and Present,” colonial history in general is (safely) quarantined in Dutch school textbooks as something that happened a long time ago and far far away, in a limited and piecemeal fashion: “there was a cultuurstelsel, there was slavery,” etc. Not only in textbooks but indeed in the wider scholarly field as well, questions of the effects and implications of the colonial experience and its ongoing legacies for the Netherlands itself—“a great part of the story” but full of complexity and difficult to fit into a “clear moral narrative” (Raben)— get passed over altogether. While one or two largely unheralded, independent scholars such as Ewald van Vugt have focused on unmasking the ugly histories of racism and violence that lay at the heart of the colonial order and continue to haunt the present—what Raben refers to as its “structural elements” of coercion and violence—the dominant “undercurrent” in public discourse has remained rather one of quiet colonial glorification: The Netherlands, as symbolized by the East India Company and the glory of the Golden Age that it underwrote, most often appears in the guise of the Little Country That Could, a nation with a remarkable capacity to punch above its weight in the global competition for riches and prestige. Such all-too-common self-congratulatory understandings of Dutch colonialism are reflected in a widely circulated poster for a current exhibit on “The East India Company and the World” at the Dutch National Archives, in which a man in 17th century garb from the neck up sports a contemporary business suit from the neck down, accompanied by the slogan “No Business Without Battle.” Thus, noted Raben, does the colonial experience live on as “shared myth.” But it has never been reckoned with as a real-life “shared experience.”

How to break through this wall of silence and address such difficult “grey areas” in a productive way? According to Verbeet, Raben, and several other speakers (including the curators of the current Bronbeek museum exhibit “The Story of the Netherlands East Indies”) an answer can be sought in exposing students to the voices and narratives of multiple participants in history and their often competing agendas and perspectives, an approach summed up in the word “multiperspectivity.” As one provocative example of an appropriate theme for such an approach in the case of the colonial Indies and its decolonization, Raben proposes prison camps. The conventional, dominant narrative of “the camps” in the Netherlands is indeed one of Dutch victimization, first at the hands of the Japanese during World War Two and subsequently at the hands of Indonesian nationalists afterwards, who ironically compelled many of the imprisoned to remain in the camps after the long-awaited Japanese surrender for their “own protection” against Indonesians with more radical, violent intentions towards them, thus piling trauma upon trauma. For the “Indo” community that had mostly remained outside of the camps, meanwhile, this was a period of infamy in which several thousand met death at Indonesian hands, a period known to them by the Indonesian term “Bersiap.” It was under the slogan of “restoring order” amidst such “chaos” that the Dutch returned to the Indies.

Yet a more balanced and less “Dutch-centric” historical understanding of this experience—one that among other things allows room for Indonesian experiences of the Dutch return as a rather different, more menacing form of “restoring order”—can for example be fostered by considering prison camps and violence in the context of a longer colonial history of political repression and internment, including violent wars of anticolonial suppression in Java and Aceh that preceded the revolution (with casualties in the hundreds of thousands) along with the prewar incarceration of Indonesian leftist activists at the infamous Boven Digoel prison island, and the exile of nationalist leaders Sukarno and Hatta to the distant islands of Flores and Bengkulu from 1934-1942 (indeed, one might well ask, how long might this imprisonment under the autocratic “emergency powers” of the Dutch governor-general have lasted, if not for their unexpected “liberation” at the hands of Japanese?)

If the day’s lectures and workshops were any indication, the appeals of such a multi-perspectival approach to colonial pasts and legacies for history pedagogy are being recognized more widely in Western Europe. Particularly impressive and ambitious in its sophistication is a French initiative for students in their last year (year seven) of high school to explore competing and conflicting memories of the Algerian War through the approaches of memory studies, which was introduced in a workshop led by history, geography and geopolitics instructor Delphine Boissarie. In this dedicated unit, students are introduced to the analyses of leading memory interpreters such as Henry Rousso, who argues that French society’s memories of the Algerian War have moved through a sequence of phases that also characterized the postwar evolution of memories of that other better-known national trauma–the Vichy regime that collaborated with Nazis during WWII—including a “phase of amnesia” and a “phase of progressive return.” But they are also confronted with alternative interpretations that dispute the very existence of anything like a “collective memory.” These rather emphasize the existence of multiple and often incommensurable postcolonial memories and their various instrumentalizations by multiple, often conflicting, postcolonial interest groups in contemporary France. Those who occupied higher status positions in the colonial hierarchy such as the elite, white, Christian “pieds-noirs” often have quite different memories of the Algerian War than the Muslim working class “harkis” who served as subalterns in the French colonial army, and the two postcolonial groups continue to stand in different relations of power and influence vis-à-vis the postcolonial French state as well. In the eyes of the many Algerians and their descendants who emigrated to France after the war, meanwhile, both groups are viewed negatively, the pieds-noirs as “exploiters” and the harkis as “traitors.”

This is social and ideological territory ripe for analysis via the nuances of memory studies, but Boissarie acknowledged some great challenges confronting the initiative as well. Teachers are only allowed a total of three or four hours of class time to cover the unit, the intellectual demands of the approach are high, students without a direct investment in the history often remain indifferent to it, and the focus remains very much on the French side of the story. Above all, the study of memory is here postulated as a method to explore the postcolonial contours and conflicts of contemporary French society—as opposed, that is, to a means of exploring, comparing, and contrasting French and Algerian experiences or narratives as such.

While their target audience is younger and their expectations somewhat less ambitious, Cees van der Kooij and Paul Holthuis, two high school curriculum developers interviewed regarding a current project to address the Dutch decolonization war in a dedicated unit for 3rd-year high school students (aged 14-15) in the morning plenary session, also agreed upon the urgent need for “multiperspectivity.” Up to now, they noted, the decolonization experience had only occupied “a page and a half” in standard textbooks, hardly enough space for nuance or multiple perspectives. As one example of the unit they are designing, they described including “three lessons on making choices: what would you do” for example as a member of the Molukkan minority—many of whom were distinguished from other Indonesians by their Christian religion and service in the Dutch colonial army—when confronted with Dutch authorities on one side and Indonesian nationalists on the other competing for your loyalty? The experience of such minorities from the “outer islands,” who shared with other Indonesians a low “native” status in the Dutch colonial hierarchy but did not necessarily feel at home or welcome in the promised Indonesian republic either, highlights the quintessential complexities and grey areas of colonial societies and their decolonization. The experience of such groups was again often quite different from that of Eurasian “Indo’s,” whose Dutch status situated them in a relatively privileged position under Dutch colonial rule, but also put them in an even more precarious and antagonistic one vis-à-vis Indonesians and their struggle for independence. What both groups shared was that great numbers of them both eventually chose a “safe return” to a Netherlands to which they had never been—and in which they were in fact rarely warmly welcomed— over remaining in a Indonesian “homeland” where they no longer enjoyed the privileges or security they had known under colonial rule.

As with the French example, the incorporation of the experiences of such hitherto unrecognized groups into history education can be said to highlight the strengths of a “multiperspectival” approach to the Dutch colonial past, but also some of its potential limitations and pitfalls. In both cases, questions arise regarding the inclusion of the voices, experiences, and perspectives of the vastly larger number of former colonial subjects who stayed behind: that is, Algerians and Indonesians. Even as Molukkans and “Indische Nederlanders” both struggled for recognition and respect from their new homeland in ways that paralleled those of France’s “pieds-noirs” and “harkis,” their large-scale exodus from Indonesia resulted in a great over-representation of their voices and perspectives in the postwar Netherlands relative to the exponentially larger number of Indonesians who stayed put. This presents an accessibility problem for historians and students eager to include the Indonesian side of the decolonization story, one compounded by the language barrier between the two societies. Both issues distinguish the postcolonial Netherlands from other postcolonial societies such as the UK, Belgium, and France—all with larger and more vocal postcolonial diasporas—and represent an extra barrier to the development of a truly balanced multiperspectivity. Symptomatic of such a problem, when asked to what degree Indonesian perspectives were included in their project, van der Kooij and Holthuis acknowleged that “Indonesia is missing” and decried a “lack of Indonesian sources.” The imbalance of scholarly attention to the Indonesian experience of the decolonization war up to now is an issue also raised by Limpach in his prominent study. Citing this, the two educators added optimistically that they expected this problem to be addressed four years from now, when the results of an ambitious new Dutch government-funded research project on “Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia 1945-1950,” recently kicked off to much fanfare, become available.

With a budget of over 4 million euros, led by three Dutch institutes (the Royal Institute of Ethnology or KITLV, the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation and Genocide Studies or NIOD, and the National Institute for Military History or NIMH) and involving a team of some twenty researchers including Limpach, the project has indeed been billed as a critical turning point in the study of this traumatic period, signalling the potential for a welcome sea change in Dutch scholarship and attitudes towards a colonial war that has thus far escaped a balanced and honest reckoning. Symbolic of this, when briefly interviewed in the mornings’ proceedings, Limpach highlighted the new research as animated by an awareness of the need for a replacement of long-used Dutch euphemisms such as “summary justice” and “police actions” for what they “really were”: “murder” (moord) and “war” (oorlog). Comparisons would again seem to be in order with French experience, in which official acknowledgement of the conflict in Algeria as a “war” came only in 1999.

Still, a closer look at the contours of the research project as currently conceived—and indeed also at the composition of this day of lectures and workshops itself—raises concerns regarding the degree to which the perennial structural underrepresentation of Indonesian perspectives on the decolonization experience in the Netherlands can be so easily addressed. The research project has sparked critical controversy for its direct connection to the Dutch state, and for its rather limited provision for Indonesian involvement and input. At the very start of the day’s session in Bronbeek, meanwhile, the audience was informed that there were no Indonesian scholars or speakers present, and that this had “everything to do with the sensitivity of this subject in Indonesia.” In their rather uncomfortable absence, a survey of Indonesian history-writing on the period 1945-50 in the morning’s final lecture was instead presented by Professor Henk Schulte-Nordholt, head of research at the KITLV, one of the institutions involved in the project.

Historically, Schulte-Nordholt observed, the Indonesian side of the story is “incredibly complicated.” But historiographically, at least from the perspective of the Indonesian state, he argued, it is “incredibly simple.” The lion’s share of his presentation focused on historical complexities he identified on the Indonesian side that bely the image of a unified national struggle against the Dutch propagated by the Indonesian state, including internal conflicts between diplomats and fighters, between nationalists, communists, and Islamists, and between social elites and social revolutionaries, with ordinary Indonesians often caught in the middle—conflicts Schulte-Nordholt summed up in the question of whether the Indonesian history of this period should be indeed be categorized as “a revolution, or a complex of conflicts?” In Indonesian history-writing thus far, he argued, the answer has been remarkably simple, and simplistic: “The Republic is THE central actor, and the state is unified.” A “second dogma” in Indonesian history writing, he continued, has been the central role of “the army as saviour of the Revolution and the cornerstone of the Republic.” Such characterizations of the past, he added, have in turn been instrumental in legitimizing subsequent social interventions in the name of preserving the unity of the nation-state, above all with regard to the army-led anti-communist terror and mass murders of 1965-1966. Also reflective of such instrumentalization of history for state ends, Indonesian narratives of the revolution have shifted over time in their identification of the primary enemy of national unity from “Islamists” to “communists” in step with shifting official anxieties about each. The long list of what is missing from all such accounts, he argued, includes attention to regional dynamics, to the fate of a federated Indonesia (which the Dutch attempted to organize as a more friendly alternative to the Republic), to the terrors of the “Bersiap” period and indeed to the stories of Indonesian war casualties as well (there are “no victims, only heroes”), or to any sense of uncertainty regarding the final outcome of the Revolution. When Schulte-Nordholt offered apparent visual confirmation of the superficial and politically skewed nature of Indonesian historical accounts of the era with a visual collage including “little dolls” (poppetjes) that he noted were a commonplace in Indonesian musea, the room filled momentarily with laughter.

Closing on a more serious note, Schulte-Nordholt alleged that the new Dutch research project is seen in Indonesia as constituting a “threat to the army’s monopoly over the history of the revolution,” a monopoly Indonesian officials have recently shown a willingness to protect through the public intimidation of scholars seeking to reopen the books on 1965. “The result is that the Revolution remains an extremely sensitive subject,” he argued, adding that while critics of the Dutch research project in the Netherlands have problematized the limited role of Indonesian participants and the possible reduction of their role to that of mere data-collectors for the Dutch, “the much more important question” is whether Indonesian scholars will be bold enough to engage in historical research whose results might conflict with the official narrative.

While the issues raised by Schulte-Nordholt are certainly valid cause for concern, his assuredness in speaking for Indonesian scholars and their concerns, along with the generally rather dismissive tone of his presentation with regard to Indonesian historiography, struck at least some of those present awkwardly. The audience was not informed about which or what sort of Indonesians were invited to the event and/or who might have turned down the invitation, but the suggestion that the prospect of intimidation by their own government is the main source of hesitation among Indonesian scholars toward participation in such an event as well as in the new Dutch-sponsored and Dutch-led research project on the Indonesian independence war would seem premature to say the least. From the standpoint of multiperspectivity championed by so many of the presenters at the days’ events, it would also seem rather ironic: surely before reaching any conclusions about Indonesians and what motivates their behavior, a minimum demand in both contexts would seem to be the provision of a space and an opportunity for a range of Indonesian scholars, and Indonesians more generally, to represent themselves. Ideally not just to speak, but also to help shape the conversation.

Whether intended or not, the manner of this presentation on behalf of Indonesians also raised pertinent questions regarding the power-effects of our own narrative framing of the (former) colonized. As noted by Delphine Boissarie in her workshop on teaching the Algerian War, whether intended or not, accusations of an alleged “failure” on the part of the former colonized to critically examine their own histories, including those that ascribe this problem to the autocratic nature of postcolonial states and a corresponding lack of scholarly freedom and objectivity of the sort that “we” enjoy in Western Europe, can carry an uncomfortably neocolonial ring. Particularly when accompanied by a failure to provide proper historical-contextual counterweight, for example in the form of reference to the role of antidemocratic, repressive colonial regimes in the genesis of such postcolonial states, as well as the often symbiotic role of Western interests in the formation and maintenance of such regimes post-“independence.” As neatly stated in a recent interview with Charles Esche, curator of the currently-running Europalia Indonesia exhibit “Power and Other Things” at the Musee de Beaux Arts in Brussels, “For 350 years, Indonesia existed under Dutch colonial administration. This means that every discussion about power requires a discussion about the ongoing effects of colonial domination.”

Highlighting the need for an awareness of the residues of colonial domination in the stories that we tell about the (former) colonized, Esche’s astute comment calls attention to the fact that when narrating colonial history, “multiperspectivity” that consists simply of a multiplicity of voices is not enough. Such histories must also be informed by an awareness of the particular structural imbalance of power characteristic to the relationship between (former) colonizer and colonized. This problem demands the fostering of a critical consciousness both among ourselves and our students not only with regard to the choice of stories we narrate and whom is speaking, but also to the power that resides in how such stories are told.

How to foster such a critical awareness among students in a classroom setting? Via a remarkable afternoon workshop entitled “Shifting Representations of Congolese Colonialism and Decolonization: An Historical-Didactic Perspective,” professor of history education Karel van Nieuwenhuyse of Leuven University offered one innovative idea for a productive way forward. Students are presented with selected short excerpts from the writings of David Reybroek, a prominent author generally perceived as a progressive critic of the way Belgians remember their colonial past. Yet a close reading highlights the dangers of such simple characterizations—and thereby the subtle ways in which colonial power and patterns of thinking continue to haunt the present. After reading an excerpted text in Reybroek’s bestseller Congo: A History that negatively compares a speech by nationalist leader Patrick Lumumba on the day Congo gained independence to famous speeches by Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, and Barack Obama, students are asked to “analyze this excerpt and the language used. Mark in green all words that ascribe to Lumumba a positive connotation, in red all negative connotations, and in blue all neutral ones. What is your conclusion? Through which lenses does Reybroek view Lumumba’s speech? Western or Congolese?” In a second chosen passage, after noting they had never lived a day under a democratic regime, Reybroek argues that it was therefore unsurprising that Congolese nationalist leaders Kasavubu, Lumumba, Tshombe and Mobutu “wrestled with the principles of democracy.” He then proceeds to reduce the interaction among them to “who should be the follower of King Boudewijn,” illustrating this with reference to Kasavubu’s choice of gala-uniform as “an exact copy of that of Boudewijn.” “Who is ascribed agency in the failed decolonization? Who much less?” asks Nieuwenhuyse of his students. “What sort of continuity is suggested between the historical kingdoms and [the situation of] 1960? How is the Congo thus represented? Connect this to the fact that Lumumba had no gala-uniform….”

Nieuwenhuyse’s lesson: In our narratives of colonization and decolonization alike, fostering an awareness not just of who is represented but also how we do so can make the difference between genuinely working to overcome the tenacious imbalances and injustices of the colonial past—and reproducing them.