By Stefan Haagendoorn

On the 12th and 13th of October, I was in Leuven, Belgium to partake in a youth event organized by the European Commission, which was focused on the question on how to form a New Narrative for Europe. As a historian, many questions immediately come to mind. What makes a narrative? Can we talk about just one narrative or are there as many narratives as there are Europeans? Or even; can we just create a narrative like that, and when is the group deciding this, representative enough?

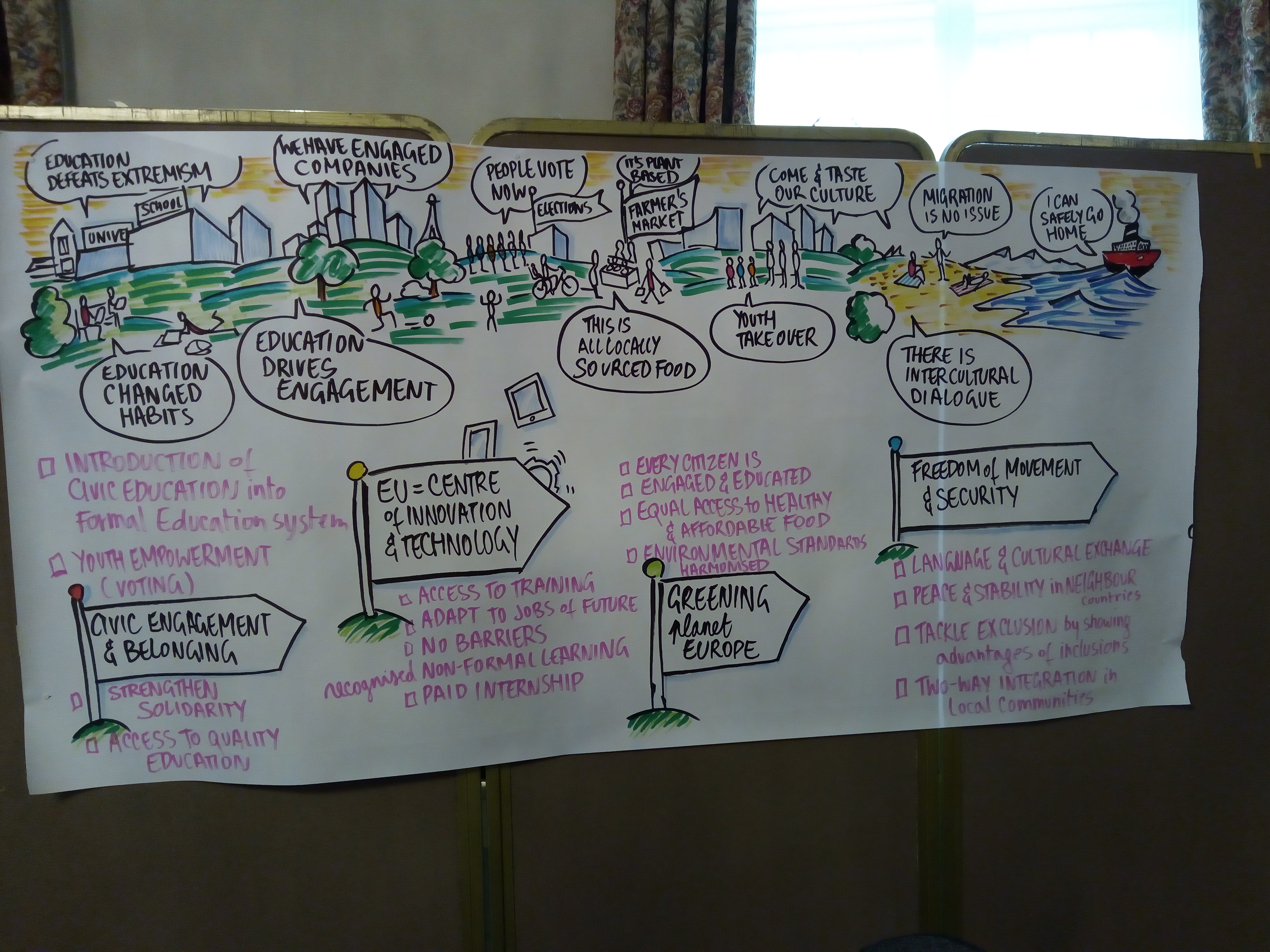

In other words, it was bound to be a discussion-laden two days. The main set-up was as follows. Gather a large bunch of young Europeans in a big room and let them discuss around four main questions interspersed with seminars and presentations. The idea was good, but given the strongly varied background of the participants, some guidance was needed. As such, the whole event was centred on 4 main questions, namely ‘’becoming united in diversity’’, ‘’employment and education’’, ‘’freedom of movement’’ and the ‘’changing climate’’. One can question whether taking these four topics is preventing an open discussion. In hindsight, I would argue that it made sure the arguments stayed on track. After reflecting on the most important issues within each of the 4 main topics, and thereby gathering our thoughts, we were asked to focus further. This was to be on no more than three ideas in total, per main question. This resulted in essentially 12 broad topics in total, which we more or less democratically decided upon to be the most critical. This caused some heated arguments, but we eventually managed.

What followed next was the fun part. In a small group of about three to four, we worked on our chosen sub-topic in order to form a narrative. The idea here was to create a newspaper front-page of about 20 years into the future, with associated headlines, pictures and text. This was to be based on the results of our group discussion. The topic I decided to partake in was centred on ‘’a common European identity through education and history’’. A contentious issue, to be sure. To give it a frame to work with, several questions were posed to us as a group, on how to form this narrative. These included: ‘’what are the actions that should be taken?’’, ‘’what are the steps required to achieve this New Narrative?’’ and ‘’who should take these actions and when?’’.

In the end, the result might be considered by some to be unsatisfactory. There was no real New Narrative, rather a list of hopes and dreams, focused on changing policy, not the people tweet about or tell each other over a drink. However positive this may be and however hopeful it may feel to collect a large group of diverse Europeans into one room, all starry-eyed about the future, it does not solve any real issues. Some uncomfortable questions were posed, mostly at the very end of the conference, such as ‘’how do we reach those Europeans that are not self-motivated to engage with it?’’ A comparison was made between a ‘’funny cat-video’’ getting a million views within the hour and Juncker’s State of the European Union address not getting any further than a few thousand. The EU and its leaders, it seems, are just not appealing. The heart of the matter here was not discussed. Other politicians (Obama, Macron, even Trump in his own way) manage to reach millions through savvy social media campaigns and appeal, at least in part, to the youth. So why not Europe? Another argument against the near-utopian narrative is its inherent tendency to always go forward. Forward sounds good and positive. But what if the best course of action (for example because the current political situation does not allow for steps towards further integration) might be a step sideways, or even backwards? This was not a popular view. Connected to this is the issue of developing something that only those that are already in the ‘’bubble’’ can identify with. How do you speak to youngsters from a Eurosceptic background? They are not going to be attracted to the same ideals as pro-EU youth are.

Notes from the meeting (picture by Stefan Haagendoorn)

As such, all the great ideas offered might then eventually be in vain. To finish off the program was a member of the European Parliament. He brought what we lacked as a group, namely an actual narrative. In short, the narrative has been, since the end of the Second World War, a negative themed narrative under the guise of ‘’never again’’. This obviously appeals less to the youth of today. As such, he proposed a positive spin, in a sense. This was that Europe is, in fact, alone. The United States for example, though still connected through shared institutions such as NATO, is seemingly carving path away from Europe. Obama had its pivot towards Asia, Trump is doing his own thing altogether. There is no other region anywhere else in the world that can then truly be called a reliable friend. This makes Europe our home and our only one at that. This should invoke a level of solidarity, which can be seen in sharing responsibility and deepening ties.

In the end, it might seem that such an exercise as this was futile. But one can’t deny the positivity that was there in the room. The last question that remains is then: ‘’where do we go from here?’’ Though some ideas were offered in the spirit of bringing this group back together at some indeterminate point in the future, I remain doubtful of that being useful. I would see more use in bringing together various other groups first (thereby making sure to try and attract those from conservative and Eurosceptic backgrounds), and then perhaps picking representatives from each of the groups to go even deeper. More serious personal contact with policy makers in both national and European governments would be another point. That more work, much more, is needed remains abundantly clear.