This is the first part of a blog post about a study visit to Cape Town, South Africa. It is the second article in a series of reports and blog posts on Dealing with the Past in History Education. A report of the visit to South Africa, written by Khaled El Masri, is available here. For more information about the project, visit the project page: Dealing with the Past in History Education.

It is after 9 PM, and I have just arrived in Cape Town, South Africa, for the first time. I am met at the airport by a driver that was arranged by my hotel, Frank Mountanda, a smiling, lively, funny, man who also happens to be an immigrant from Congo. As he took my luggage and was putting it in the trunk of the car, I walked up to get into the car, and he started to laugh and said, “You are welcome to drive it you want.” Without thinking I had walked up to the driver’s side of the car, which is on the opposite side of where it is in the United States. I had just done what was normal for me to do, proving that we humans definitely are creatures of habit.

The word “habit” is an interesting word. Its meaning is simple enough: it is something you regularly do that is often times hard to give up or change. It is needing to brush one’s teeth every morning before work, biting one’s finger nails, smoking cigarettes, or benignly walking to the wrong side of the car. Habits are not inherently bad; many are good, but they are most certainly difficult to change. We get used to doing a thing, and it becomes common practice. It is just what we do.

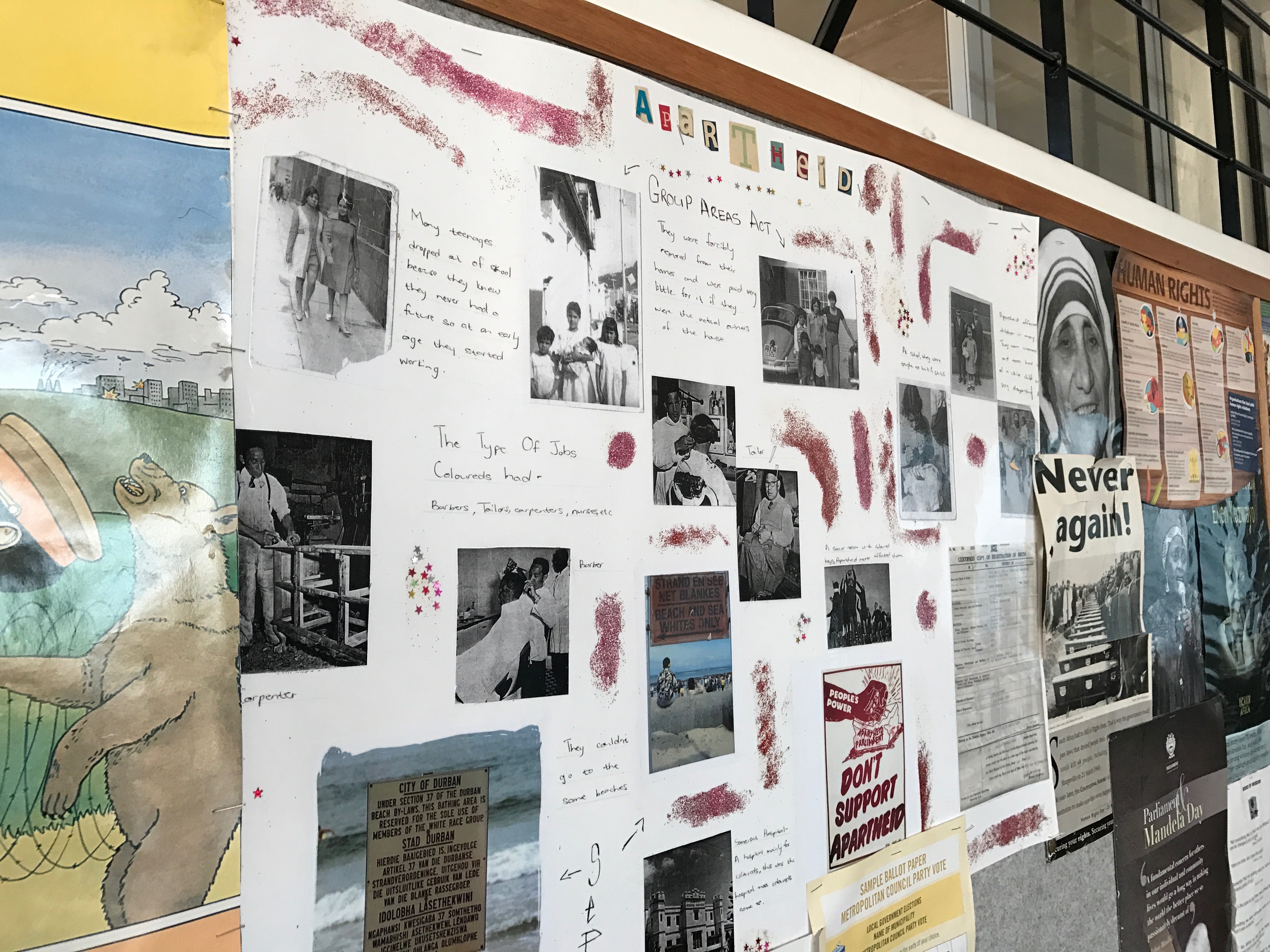

What if you grow up in a society where the social norms dictate that you separate yourself from people who look different than you, perhaps a place where white people don’t use the same public buses or bathrooms as black or colored (mixed-race) people? It is just normal life. How does a society go from changing the mindset of its people so that one group is not superior to all other groups? This has been the challenge of South Africa since ending apartheid— institutionalized racial segregation laws and practices— in the early 1990’s.

While I was visiting the South African Jewish Museum, I talked to Roz Von Zaiklitz, one of the museum’s tour guides and experts, as she reminisced about a story when she first came to South Africa from nearby Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). While standing in front of a sign on the wall entitled “Facing Reality,” she tells the story of when she was a young student, barely 18, waiting for the first time for the bus in Cape Town. When the bus stopped in front of her, she did what she always did back home, she started to board it. However, the driver stopped her and said, “Sorry but my job is more important to me than letting you get on this bus.” Roz was confused by the driver’s reaction, because all she wanted was to ride the bus to the university. She then saw the driver point to a sign. It said in Afrikaans, “SLEGS NIE-BLANKES,” or in English “Non-Whites Only.” Roz was trying to board a bus for non-whites, and this was against the law in apartheid South Africa. This was her welcome to South Africa’s reality.

Years after trying to board that bus, in 2000, Roz was standing in line with other museum employees at the opening of the South Africa Jewish Museum. They were in line to welcome their guest of honor, Nelson Mandela, as he was there to officially open the museum. Roz recalls how excited everyone was to meet the great Madiba, the name South Africans use for Nelson Mandela. She said, “We were all crying and smiling” to meet this “larger than life hero” of South Africa.

This brings me to the purpose of the trip to South Africa, which was to interview several South Africans in order to gain some understanding of the important role education plays, particularly history education, in helping the people of South Africa, young and old, deal with the difficult past of living in a post-apartheid South Africa. Joining me on this task was Khaled El Masri, a history educator from Lebanon. Our job was to pose the question, “How can history education help with dealing with a difficult past?”

Our first stop was the IJR, the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation, where we had the pleasure of working with and interviewing Cecyl Esau, Senior Project Leader for Building Inclusive Societies, and Lucretia Arendse, Project Leader for Education for Reconciliation. Both of them work in IJR’s Sustained Dialogue Programme. Essentially, their jobs are to put into practice the essence of our proposed question. Their work / projects revolve around dealing with South Africa’s difficult past and how to bridge the divide that apartheid created between people of different races.

“Make way for the uncle.”

In our first conversation with Cecyl Esau, he relayed a recent story of himself visiting the market. Telling his story, he started by clarifying what he meant when he said “Black South Africans.” He stated, “When I say black people in general, I mean black Africans, and coloreds, and Indians.” He said in the past “we (meaning Black South Africans) were not spoken of with familiar terms.”

I wasn’t quite sure what he meant when he said “familiar terms,” but as he continued with his story it made perfect sense. While walking through the grocery store he recalls a white mother telling her white daughter to “make way for the uncle.” The term “uncle” is used as a respectful term for older South Africans. In the past a white person would almost never have referred to a black person as “uncle.” It would have been, in Cecyl’s thoughts, too “familiar.”

It is not just young white mothers with children changing attitudes toward blacks. According to Cecyl, older whites will now make “small talk,” whereas in the past they would be more likely to ignore the black person standing or sitting next to them. Cecyl ends his story saying, “There is some movement when it comes to making overtures to other people, unlike under apartheid.”

These are just a few small indications of the positive strides made in South Africa in the past twenty years, but the work Cecyl, Lucretia Arendse, and all the others at IJR do on a daily basis helps to ensure that these small, positive stories translates to a more “fair, democratic, and inclusive” society, as their vision statement states.

Woundedness

One part of Lucretia Arendse’s work deals with creating curriculum for teachers to use in order for them to have these difficult conversations with their students about the apartheid past. The purpose of such lessons is the hope that it will help with achieving the IJR’s mission of promoting reconciliation and applying “human-centered approaches to socio-economic justice.”

Teachers need to ask themselves: “What wounds are you carrying that make it difficult for you to be accepting to the other?”

While presenting to teachers, Lucretia and others from IJR became aware that the teachers themselves found teaching lessons about apartheid and reconciliation to be difficult and emotionally challenging. Since most of the teachers grew up in an apartheid South Africa and knew first-hand the cruelty and injustice apartheid inflicted, many of them simply did not have the ability to teach to their students what was meant to seek reconciliation.

Lucretia recalls what teachers would tell her, “We can’t give what we do not have.”

Lucretia then posed the question, “What wounds are you (the teacher) carrying that make it difficult for you to be accepting to the other?” In order to teach reconciliation, teachers had to face their own “woundedness.” Teachers would need more specific training on how to go about dealing with the difficult issues they would face in their classrooms. They needed to practice scenarios that they would face and possible solutions they could enact.

Walking with anger

It is not just teaching teachers in order for them to teach their students. The reality in South Africa is that the student’s parents have the same difficulties and challenges that the teachers face in dealing with their own wounds attributed to the apartheid past. As Lucretia Arendse stated:

There is that inter generational trauma that is passed from parent to child and you wonder why children are prejudiced? How do you, as a school, get your parents on board to come along side you…you are teaching one thing in the classroom and they go home and parents are teaching them another thing.

Create an awareness.. you need to get your parents involved.

Creating a school culture where parents are an integral part of the learning process is not as easy as creating curriculum for teachers. It will require structural changes in school districts and schools to find ways to best meet the needs of their diverse student populations. It will require school leaders and community leaders to work together to find ways to bring all stakeholders together in ways that will help all involved deal with their difficult past so that the future will be one of corporation, mutual respect, and peace.

Lucretia Arendse answered our question on the importance of history education this way:

We have to understand where we come from in order not to go back there. If you are walking with anger or you are walking with shame as a white person then how does that transfer to children. This has to be taught in all subjects. We want learners to understand what was the past, an inclusive perspective of the past.

The past in South Africa just cannot be forgotten or ignored. It is the past that impacts their present and continues to frame their future. For South Africa to reach the reconciliation, hopes, and dreams of the rainbow nation it must be with confronting the difficult history of the past with tough courageous conversations in the schools, in the homes, and in the communities.

This is the first part of a blog post about a study visit to Cape Town, South Africa. It is the second article in a series of reports and blog posts on Dealing with the Past in History Education. A report of the visit to South Africa, written by Khaled El Masri, is available here.