The original article was written by EuroClio Ambassador Jonathan Even-Zohar on his website

It’s 2025 and you are looking at buying a house. Before you do, you access your timemachine, which puts you in a historical geographic information system. Maybe it’s an Assassins Creed-type immersive experience, or maybe it’s more like a Google Streetview. But whichever it is, you are free to encounter time- and location-specific primary source materials. Not only that. You might also be able to look ‘behind the scenes’ at different interpretations and connections between primary sources across various interpretations in society of said primary source…We are talking annotations, enriched stories, thematic pathways and much more. Before you know it, you have browsed through several centuries of change and continuity in and around your possible house.

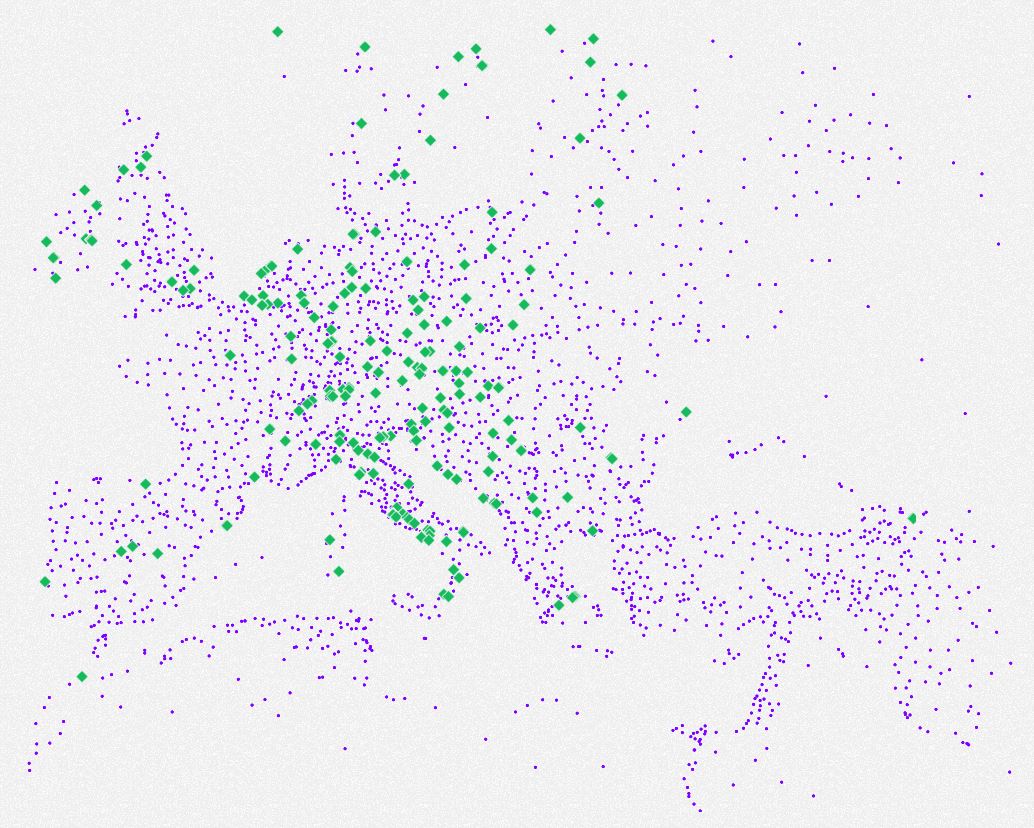

This is Timemachine. Born from a desire to radically scale up the Venice Time Machine project (documented very well by the Arte Production “History and Big Data”), the partnership now brings together over 200 institutions from all over Europe. It brings together innovators, networks and users in many fields, including archives,artificial intelligence, data science, gaming, heritage, history and visualisation. One of my favorite organisations, Europeana, is a core supporter as well! What do they want to do, and how?

It’s an exciting time for this initiative as in the coming days the European Union will publish it’s selection results. If positive, the initiative will receive major funding in the years to come!

The initiative website already provides much information about the approach, the vision and the partners – but what would such a time-machine mean for the future of history and history education?

I spoke with Dr Thomas Aigner, Steering Committee member of Timemachine and President of Icarus (International Centre for Archival Research), to find out more about this vision and its implications.

Historians Needed

Timemachine is pitched to bring about a new paradigm for the historical sciences. This involves many new disciplines (AI, robotics, data, physics, etc.), but Aigner holds that the historians’ method of investigation, the philosophy and above all the art of interpreting will make historians more important than ever. No longer will historians be seeking for a needle in a haystack. Instead the masses will be playing around,educating themselves with needles and hay alike. Historians need to foray into designing user experience of interpretations. Much of which resides already in historical pedagogy and cultural heritage education already.

While the project expects to achieve technological breakthroughs in, for example, AI-enabled deciphering of historical scripts and smart translation, it will still be the responsibility of historians in society to assess sources, connect dots critically and tell stories. Only difference will be that they will no longer hold a kind of monopoly to the historical record.

This, one might say, is a process already very much in progress. Public historians seek to further understand their position in an increasingly digitized historical record.

Just as in the 19th century, being overwhelmed by the alleged “experience” of past times in some cases undermines the least distance to the historical subject presented. The borders between the individual-temporal levels become blurred and the observers run the risk of perceiving the representations as mirrors of the past without any reflection. This phenomenon can also be recognized with meticulously investigated Virtual Reality offers which, “in historical terms”, are as exact as possible. (Virtual Time Travels? Public History and Virtual Reality;Public History Weekly)

Trust in Data? Google? Europe?

Aigner talks about the imperative to “liberate the Big Data of the past” and make it accessible for all, in passing also referencing the need for Europe to do this “before Google does it”.This seems a very valid concern! Not only has the Google Books project been a warning shot in terms of figuring out “who owns heritage” (check out the 90 minutes documentary Google and the World Brain if you have a chance), but also in terms of how Google approaches knowledge through AI and algorithms. Playing around for example with “Talk to Books” shows that while it can be easy to find out what books say by asking questions, the perception on the validity of that knowledge, in my view, falls behind the accumulated contextual knowledge of historians, who are trained to cross-reference, as well as “read between the lines”.

Also Google Arts & Culture has featured extensive browsing capabilities of heritage markers.

Be that as it may, how does the noble goal of “liberating data” relate to the cluster of problems around fake news, disinformation campaigns, political echo chambers and polarization in public discourse?

Well, that struggle will go on. Aigner agrees that use and abuse of the past is not something to be resolved with technological breakthroughs. And perhaps Technology is actually part of the problem? But, removing the barriers (access, language, relational, etc) to the historical record will enable all stakeholders to better research, narrate and experience the past. Timemachine essentially is about the creation of the tools necessary to open to a new world of technology-enabled-history, including “to develop new technologies for the scanning, analyzing, accessing, preserving and communicating of cultural heritage at a massive scale”.

…and Education?

Technologies in virtual/augmented/mixed reality, big data and AI are very promising, and Europe’s thirst for recreational, intellectual, political or simply personal historical experiences, will certainly help in pushing the envelope. Even we can see this as a form of democratisation of the past. Fair enough.

In education, however, the process of learning matters. There are pedagogical concerns and the question of the role of technology in learning still looms in the educational field. Timemachine might eventually offer learners experience which create ‘historical sensations’.It might inspire far more original archival research and even source analysis and critical thinking. But if will still need educators to run the show.

It seems a process which is just starting. While education policy makers orient themselves to the need to address democratic values, skills for the 21st century and so on. “Technology may enhance teaching, but requires good pedagogy and skills”, say the authors of Teaching in the fourth Industrial Revolution. I will need to read more and seek to follow these teachers.

Dots on the Horizon

Every citizen will be able to access rich historical data. The big funding from the EU should facilitate the building of a “massive semantic graph of linked data –probably the largest ever built about the past – unfolding in space and time as part of an historical geographical information system”. Still an overly academic project, hence the large EU science funding in the form of FET-Flagship, one can only hope translations to citizens of all ages through public,and general education, get prioritised as well.

Of course, as a historian, I am thrilled to get my hands on this technology. Already working with the Dutch National Library Delpheronline archive of newspapers has been an amazing experience and inspiring to do more research. But the idea of a massive single linked approach certainly is incredible.

Also I can see much enthusiasm in the field of cultural heritage, where so many different public authorities(museums, municipalities, provinces, etc) and private entities (tourist companies, seek to provide tourists and the public at large with immersive experience, in which the past can be experienced and more.

Exciting times ahead for sure.

But then I imagine. We have reached the new reality. Big Data of the past has been liberated. A plethora of new research emerges. The public is unable to ignore historical perspectives and anew layer to daily life is made possible. And then you look at the house your about to buy, and you see that is was an SS-headquarters during the Nazi occupation. Or, more to the point, you figure out that the house you are about to buy features high on crime. You won’t go there. The house price drops, and social cohesion with it…Perhaps you see the garden was the site of witch burnings.

Metaphorically, people have described history as a vast ocean of inspiration, but also as the monsters under the bed.

And it is at that point that some questions are likely to remain:

- How will the public-at-large navigate the moral waters of history?

- Are we at risk of algorithms catering for us to view only the history which is recommended to us? Like with Netflix,Amazon, etc.

- Who will govern the data to the extent that the user behaviour might render some historical sources more valuable than others?